I’m taking the day off today, so please enjoy these images of Isis’ temple at Philae from our Egyptian journey. It truly is the most beautiful of the surviving temples because of the stunning location.

I’m taking the day off today, so please enjoy these images of Isis’ temple at Philae from our Egyptian journey. It truly is the most beautiful of the surviving temples because of the stunning location.

Trees are sacred. And the more we know about them, the more we understand how very sacred they are.

The ancient Egyptians, of course, knew this, too. There were a number of trees they held sacred. Yet, perhaps the most intriguing was the ished. The ished is particularly intriguing because it remains a bit mysterious for it has not yet been identified with complete certainty.

And yes, of course, Isis is connected with this mysterious and sacred tree. She is, after all, one of the Egyptian Tree Goddesses.

The Ished in Myth

Mythically, the ished is one of the holy, solar trees associated with Re. It was the sacred tree at Heliopolis on top of which the bennu bird—the phoenix—was eternally reborn in fire. And it was the Tree of Life upon whose leaves and fruits Thoth and Seshat recorded the years of each king’s rule. The tree was also associated with the dead, with renewal, and with Isis’ beloved Osiris, “He Who is in the Heart of the Ished.”

But What Tree is It?

Modern Egyptologists have variously identified the ished, with some of the confusion coming from the fact that the Egyptians themselves seem to have used the word for more than one tree.

In addition, there is some mythological overlap between the ished and another Egyptian sacred tree, the shwab. The most common identification of the ished/shwab today seems to be mimusops laurifolia, an evergreen hardwood tree with fragrant, white flowers and fleshy, eatable fruits. The wood can be used for carpentry and extracts from the bark can be used for tanning leather. It is native to the Ethiopian highlands and now rare in Egypt.

Others have identified the ished as balanites aegyptiaca, a spiny, semi-deciduous desert tree bearing smaller, oval fruits with purgative qualities. Fruits, leaves, and seeds of both trees have been found in Egyptian tombs; minusops leaves were also used in funerary wreaths.

The Persea & Isis

You will also see the sacred ished called by the Greek word persea. In fact, this is the most common name under which you’ll see the tree discussed.

The Greek priest Plutarch is a key source for connecting Isis with the persea. He tells us that the persea is especially sacred to Isis “because its fruit is like a heart and its leaf like a tongue.” He goes on to explain that this is because no human quality is more Divine than reason (especially when it concerns the Deities) and that there is no more driving human force than happiness.

So Plutarch is connecting Isis and the persea with two essentials of human life: relationship with the Divine via reason, and joy of the heart. Of course, this is Plutarch’s Hellenocentric interpretation. A more Egyptian interpretation might be that the heart-shaped fruit refers to the powers of the Goddess to bring forth “what Her heart conceived” while the tongue-like leaves represent “the magical power of Her mouth, being skilled of tongue.”

But we’re not quite out of the woods (so to speak) yet.

Ancient Greek and Latin writers applied the name persea to at least two Egyptian trees. According to the 4th-century-BCE Greek scholar Theophrastus, who made an extensive botanical study entitled Inquiry into Plants, in Egypt there is “another tree called the persea.” He tells us that this persea is large, attractive, and most resembles the pear tree “but it is evergreen, while the other is deciduous.” Theophrastus says that this persea is found only in Egypt.

Generally, Egyptologists today think the ancient authors were referring to the mimusops as the persea. Though, if Theophrastus is right and his record reflects Egyptian usage, the name persea was used for several trees. Which would explain the confusion about its identity.

Theophrastus’ description of the fruit of this evergreen persea is interesting, too. He says that the fruit is gathered unripe and stored. It is about pear-sized, but is “oblong, almond-shaped, and its color is grass green.” He describes the stone inside as like a plum, but smaller and softer. The flesh is sweet and luscious and easily digested and he mentions that it doesn’t cause problems even if eaten in quantity. (It is important to note that when the Greeks used the word “sweet,” they often meant “mild,” not sugary sweet.) Theophrastus’ description seems to better suit the mimusops, the fruit of which is described as delicious, rather than the smaller, purgative fruit of the balanites. Yet mimusops fruit is rounder rather than almond shaped, so perhaps the persea retains its mystery.

Osiris & the Persea

In addition to Isis’ connections with the heart-like fruit and tongue-like leaves of the persea, Osiris has His own persea associations. One of His key symbols, the djed pillar, is a stylized tree. The djed is sometimes shown with eyes and arms that hold the Osirian crook and flail, as if the God were alive within the pillar—causing some Egyptologists to suggest that He was originally a tree spirit.

You may recall that in Plutarch’s telling of the Isis myth, a tree magically grows up around the coffin of the murdered God and is later made into a pillar. In this way, Osiris is indeed within the tree and within the pillar. That tree, too, has been variously identified, from erica to tamerisk to cedar. But if Osiris is the Heart of the Ished, it seems reasonable to assume that the tree that grew up around the body of the Tree God was the holy ished or persea.

A Ptolemaic text records the dedication of an altar and a grove of persea trees to Osiris, Serapis, Isis, and Anubis. In the Roman period, a member of Isis’ Philae temple staff, recorded his good deed of planting four sacred shwab trees, one at Her temple, and three in or outside the nearby town.

We Can Still Honor Isis with Persea Today

While it is unlikely that we will be able to find either the fruit or the leaves of the ancient Egyptian persea today, there is a persea readily available to many of us.

It is the persea americana, our supermarket avocado. Originally from Central America and Mexico, the avocado is a member of the genus persea, evergreens of the laurel family. The persea americana was first so named by the English botanist Philip Miller in 1768. Theophrastus’ description of the Egyptian persea’s fruit no doubt influenced Miller’s choice because his description of the persea’s fruit fits the modern avocado rather precisely.

So, if you wish to honor Our Lady of the Tree—Who conceives in Her heart and speaks All Things into being with Her tongue—you might consider offering Her a lovely bowl of beautiful, green avocados.

Dear rebels and resisters, I want you to know that Our Lady is right there with us.

It seems to be part of Her nature.

Interestingly, quite a number of ancient Athenian Isiacs—living under Roman imperialism—chose to have themselves represented on their tomb steles in Isiac dress as a way to reclaim some of their own individuality.

An article I was reading about this suggested that these people wanted to represent themselves in other than the standard Greco-Roman manner because it let them preserve some of their self definition and personal power (as well as cultic status) in an era when they felt they had little of it politically. And, of course, these people were mostly, but not all, women—people who have had little political power at the best of times, in ancient society and now in far too many places.

In other words, these people were rebelling against Roman societal rule in a way that helped them fashion new and more complex selves—and Isis helped them do it.

Oh, but it started much earlier than that.

Although you still see Isis described as “the ideal wife and mother”—which often has connotations of 1950s housewife—I’ve always thought of Her as quite rebellious in that She always does exactly what She wants to do, and does not let anything stop Her.

That’s why I was taken aback when a friend once remarked to me that she couldn’t get into Isis because of the subservient way She went around “picking up after Osiris.” My friend was, of course, referring to the main Isis-Osiris myth in which Isis travels the length and breadth of Egypt to find and conduct proper funeral rites over the scattered pieces of Her murdered husband’s body.

I, on the other hand, have always considered the ancient myth of Isis to be pretty darned feminist, modeling both feminine power and independence. Indeed, my own feminism is one of the reasons I began exploring Goddess in the first place.

My friend had seen the Isis-Osiris myth as just another “woman-taking-care-of-her-man” story, while I’d seen it as precisely the opposite: a tale of the reversal of stereotypes. Instead of the prince saving the princess, the princess had to save the prince, put him back together, and give him renewed life.

We were both right, of course. A myth speaks to us however it speaks to us. Nevertheless, I think that Isis and Her cycle of myths, especially when you include the important Isis & Re story, provide a proto-feminist model.

Part of the credit for this goes to ancient Egyptian society. While we should have no illusions that men and women were true equals in Egypt, still they were more equal in Egypt than in any of Egypt’s Mediterranean neighbors. In Egypt, women could hold and sell property; they were considered (at least theoretically) equal to men before the law; they could instigate lawsuits; they could lend money; and although it was unusual, a woman could live independently, without a male guardian. In contrast, Greek and Roman laws firmly relegated women to control by their husbands or male relatives and provided little economic or legal protection to women.

So when Isis’ myths depict Her acting autonomously for Her own ends or wielding power, this type of female behavior was not as strange in Egypt as it was in the rest of the Mediterranean world. Another example of Isis wielding power are the tales of Isis as warrior that we have from the tales in the Jumilac papyrus.

Even when Egypt was ruled by non-natives under the Ptolemies (from 305 to 30 BCE), the native Egyptian respect for the feminine and The Feminine seems to have crept in. By the end of the dynasty, the historian Diodorus Siculus (Diodorus of Sicily) could write that due to the success of Isis’ benevolent rule of Egypt (while Osiris was on His mission to civilize the world):

…it was ordained that the queen should have greater power and honor than the king and that among private persons the wife should enjoy authority over her husband, the husbands agreeing in the marriage contract that they will be obedient in all things to their wives.

Diodorus Siculus, Book II, section 22

This wasn’t true, but it is interesting that it would be the impression that Diodorus received when visiting Egypt and speaking to Egyptians.

I’m also reading an article in the Journal of Hellenic Studies by Rachel Evelyn White about women in Ptolemaic Egypt that discusses the possibility that the family tomb may have been the property of a female heir, and which was likely a holdover from ancient Egyptian tradition. This is based on some Egyptian contracts of the time combined with the fact that this was specifically the case among the nearby Nabataeans. If so, this could be one of the bases for retained female power in Egypt, as well as giving women another connection with Isis as the provider of proper burial and funerary rites. It may also point to very ancient matrilineal (not matriarchal) traditions in Egypt.

We should also recall that in several of the remaining Isis aretalogies, the Goddess declares women’s equality with men. What’s more, the relationship between women and men is meant to be friendly and loving—like the relationship modeled by Isis and Osiris. The aretalogy from Maroneia states that Isis established language so that men and women, as well as all humankind, should live in mutual friendship.

In a later Hermetic text entitled Kore Kosmu, Isis explains to Horus the origin and equality of male and female souls, declaring that:

The souls, my son Horus, are all of one nature, inasmuch as they all come from one place, that place where the Maker fashioned them; and they are neither male nor female; for the difference of sex arises in bodies, and not in incorporeal beings.

Scott, Walter, Hermetica, Vol. 1 (Boulder, Colorado, Hermes House, 1982), p. 499-501.

The Oxyrhynchus Invocation of Isis states it quite plainly: “Thou [Isis] didst make the power of women equal to that of men.” I know of no other ancient texts that lay out the message of equality so strongly as is done in the Isis aretalogies and hymns.

And so, I honor Our Lady, Isis the feminist, Isis the rebel and resister. May She help and support us in this difficult time.

After a few weeks, I’m finally getting back to Dendera and some of the texts inscribed on the walls of the small Isis temple there.

As you may recall, the temple is sometimes called the Birth House of Isis, which celebrates the birth of Isis from Her mother Nuet.

One of the temple walls says explicitly, “On this beautiful day, the day of the Child in His Nest, a great festival throughout the country, Isis is given birth at Dendera by Thoueris [“The Great One;” in this case, meaning Isis’ mother Nuet] in the House of the Noble One [the Noble One is Isis], a woman with black [kemet] hair and red [desheret] skin, full of life, Whose love is sweet.” Her mother Nuet says that She “makes every person rejoice to see You [Isis].”

With Her kemet hair and desheret skin, the Goddess encompasses the Black Land and the Red Land of Egypt. You may also recall from last time that this temple is very much concerned with the sovereignty of Isis over the entire land of Egypt.

Another temple inscription says, “Destiny distinguishes Her on the birthstones. Her heart is rich in all virtue. The south is given to Her until [that is, “as far as”] the [place of the] rising of the Disk, the north until the limits of Darkness. She is mistress of the sanctuaries of Egypt with Her son and Her brother Osiris.” She is “Queen of Upper and Lower Egypt.” She is “Mistress of the cities and Sovereign of the Nomes, the Sovereign of Sanctuaries.”

As this is the temple of Isis’ birth, we have many Birth Goddesses present, including a form of Isis Herself. We find Meskhenet, the Birth Goddess Who sometimes takes the form of a personified birth brick, in four different forms. Meskhenet the Great in the Mound of Tefnut is Tefnut Herself. Meskhenet the Great in the Mound of Birth is Nuet. Meskhenet the Beautiful in the Place of Nativity is Isis. And Meskhenet the Excellent in the Temple of the Menat Necklace is Nephthys.

However, in a different part of the temple, the four Meskhenets are Djedet (Djedet is the principle Goddess of the town of Djedet, also known as Hatmehyt. Learn about Her connection with Isis here.), Nuet, Meskhenet the Beautiful in the Enclosure of Life, Who is Isis, and Meskhenet the Excellent in the Heart of the Land, Who is Nephthys; She is also called Efficient (Akh) for the Daughter of Geb (although Nephthys is Herself a Daughter of Geb, this likely means that Nephthys is akh for Isis).

And speaking of Nephthys, here are some more of Her epithets found in this Isis temple: She is The Excellent and The Efficient. She is the One Whose Breast is Shimmering. She is the One Whose Face is Beautiful, the Mistress of Adornments, and Mistress of Light in the Cavernous [Zones]. (See? Nephthys is not always the Dark One!) And both Sisters’ mother Nuet is called The Unknowable. Which I love so much. All my Goddesses are, ultimately, Unknowable.

This small temple is the source of one of the inspirations for what will be one of our ritual acts at SunFest, our local summer solstice festival in June. There is a section of a wall labeled “Spreading a dusting of gold and green earthenware on the ground at the Mound of Birth.” The Mound of Birth is the place where Isis is born. It is also the place where the entire world is born, when it first emerges from the primordial Waters. It is well to honor this sacred place within the temple. Indeed, all temples were considered to be the Primordial Mound where the world first emerged from the Waters.

What caught my eye in this case was the idea of scattering gold dust and powdered green faience in this holy place as a consecration. It reminds me of the colored powders scattered during the Indian Holi festival. During our Festival of the Return of the Wandering Goddess, we’ll be doing something similar and scattering dried flower petals in the path of the Returning Goddess to consecrate the Way of Her Return. If we happen to get some on each other in the process, oh well.

While Isis, in Her birth temple, is said to be the First One Born Among the Goddesses, nevertheless, Hathor as a Cow Goddess is there at the same time and licks the baby Goddess Isis on the day of Her birth—just as mother cows lick their calves at birth. (Of course, Nuet can also be a Cow Goddess; She is, in fact, the Cow Goddess referred to in the famous text known as The Heavenly Cow.)

At Isis’ birth Hathor sings, Khnum makes the “Divine body” of the Goddess, that is, Her sacred temple image. The ka and the hemsut (feminine fate spirits associated with the ka) rejoice as They receive Isis’ Mysterious Image, that is, Her temple statue. Nekhbet as the Uraeus vows to sit upon Her brow to protect Her. Other Goddesses also vow protection for Isis as Thoth promises that He will write Her stories.

One of the parts of the temple is called the Sanctuary of the Vase, which the king made for Isis “to protect Her body in his sanctuary in joy, to preserve Her Divine Images there.” Isis is said to enter “Her chapel in the Land of Atum, Her heart is glad to enter there.” The Sanctuary of the Vase then is the storage area for Isis’ sacred images and the Goddess is pleased with the images and so She happily enters into the image and Her sanctuary. The king has made the sanctuary for She Who is Full of Life and the images “are excellently chiseled by the work of the sculptors, enhanced with gold to perfection.”

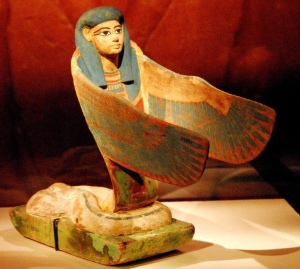

Here’s another thing I found interesting. One temple text says that the bas (manifestations/powers/a mode of Divine Being) of all the Deities follow the ba of Isis and They “melt” over Their effigies on the walls in joy.

I am very much intrigued by the idea of Isis’ ba—an aspect of Her Divine energy that indwells Her sacred image—melting over the image. Sometimes the Divine ba is said to swoop down from the heavens like a bird to alight on the sacred image. But melting over and into it—infusing the image with Her ba—really catches me.

I shall definitely use that visualization the next time I invoke Her to the sacred image that dwells in my home shrine for Her. And that is something else to note. We don’t just invoke Our Divine Ones to Their sacred images and call it done. Each time we invoke Her, She comes anew. Each time we ask Isis to come to us, come to us, She once again “melts” over Her sacred image.

That’s as far as I’ve gotten in my books for now. I’ll share more of what I learn as I go along.

How many of us were Egyptophiles from very early on in our lives, even as children? That’s true of me. You, too?

The power of ancient Egypt is magnetic, irresistible. And our Goddess Isis is perhaps THE most well known—and for some of us, most magnetic and irresistible—of the representatives of Her ancient homeland.

We are not alone in our attraction to Egypt and to Isis. We’re not alone today, and we’re not alone historically. Fascination with Egypt and devotion to Isis spread far beyond the borders of ancient Egypt. In the beginning, Isis was a local Deity. Eventually, Her worship and that of Osiris spread throughout much of Egypt. By the 5th century BCE, the Greek historian Herodotus said Theirs was the only pan-Egyptian worship. (This isn’t so, but it shows how widely their worship had spread within Egypt.)

Even during archaic times (as early as 800 BCE), we see traces of devotion, such as inscriptions or votive images, outside of Egypt. By the 4th century BCE, Isis and Her family were adopted into Nubia to the south of Egypt and Greece to the north. Then, from the beginning of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt (305-30 BCE) through the Roman Empire, devotion to Isis spread very quickly.

Due to some ancient documents we still have, we can know that the first temple of Isis was built in Greece, in the Piraeus, Athens’ port city, by the late 4th century BCE. I found an article detailing how that may have come about.

The first thing we hear of it is in a legal document that the folks who had received said document had carved in stone and set up in the Piraeus. They wanted to make sure there would be no mistake that they had proper permission. The people who had it carved were from Cyprus and they had gained permission to set up an Aphrodite sanctuary. The interesting thing for Isiacs is that they had done it on the precedent of Egyptians having built a sanctuary of Isis in the same area. The document is dated to 333/2 BCE. So this means that the formal worship of Isis was established in the Athens area sometime before 333/2 BCE. On the Greek holy island of Delos, sometime about this same period, an altar dedicated to Isis is the oldest of the inscriptions related to the Egyptian Deities.

The person who had proposed that Athens grant this permission to the Cyrians was a guy named Lycurgus who was in charge of Athenian finances, and so was quite powerful. At least one scholar has suggested that he had something of a personal interest in the previous Isian sanctuary. His grandfather, also named Lycurgus, may have been the one who proposed that the Egyptians be allowed to build their sanctuary. If it was Lycurgus senior who was connected with the Egyptians and their sanctuary, then that would put the establishment of an Isis temple at Athens about the late 5th century BCE.

However, getting foreign sanctuaries built was not an easy thing. And in fact, Lycurgus senior was thoroughly mocked for his promotion of the Egyptian Deities. He was nicknamed “Ibis” in Aristophanes’ comedy, The Birds. An ancient scribe commenting on this nickname opined that he was called that either because he was Egyptian by birth or due to “his Egyptian ways.” A fragment from another comedian pictured Lycurgus wearing a kalasiris, the long, form-fitting sheath dress of an Egyptian woman. Yet another suggests that Lycurgus might be carrying messages home to “his fellow countrymen” in Egypt.

Most scholars are pretty sure Lycurgus senior wasn’t Egyptian—and are certain that he was an Athenian citizen—but it seems that he may have indeed been an Egyptophile. What we don’t know for certain is whether Lycurgus the younger was actually the grandson of Lycurgus the Ibis. So there may be no connection at all and the names merely coincidental. The author of the article I’m reading suggests that grants to both to the Isis and Aphrodite devotees may have been more political than religious. Athens had suffered some defeats during this time period. The author suggests that Lycurgus the younger was welcoming sanctuaries from other areas so that he could help build up Athens’ trade and thus its economic power. So it’s always money.

While it may have been money for Lycurgus the financial administrator, it wasn’t just money for other Isis-interested people in the Mediterranean. For instance, we see more Greek parents giving their children names that included Hers at about these same times. Scholars generally agree that when we see an upswing in what are known as theophoric names (“Deity-Bearing” names; for instance, “Isidora” is a theophoric name), we are witnessing an increase in the Deity’s popularity as well. In Greece, we see a few Isis-bearing names in the 3rd century BCE, many in the 2nd century BCE, then an absolute explosion of Isis names from the 1st century BCE through the Roman Imperial period.

Perhaps even more interesting is that people may have taken names that included Hers as a sign of their devotion. This is not so different today. My own theophoric name is a taken name that I legally changed to permanently connect me with Her. And I know I’m not the only one.

Isis may have been especially important in Miletus, an ancient Greek city in what is now Turkey. There are five women, known from their funerary reliefs, who all bore the name Isias (or Eisias) and had come to Athens from Miletus. Some scholars have suggested that these women may have been former slaves who were freed in the name of Isis and therefore took the name of their deliverer. Others have suggested that they were initiates of Isis who took Her name—or that they may have been both.

The five Isis-named women were shown on their grave reliefs in the famous “dress of Isis,” that is, the fringed mantle with Isis knot, and holding the sistrum and situla. But theirs were not the only examples. In fact, we know of 108 such Attic reliefs of women and some men with Isis attributes; the women wear the Isis-knotted dress, while the men hold the sistrum and situla. During the Roman period in Athens, this number makes up one-third of all the known (and published) grave reliefs. If that number reflects true percentages rather than just chance, that’s an awful lot of Isiacs.

In addition to the possibility that these Isis-accoutered people were initiates of Isis, it has also been suggested that they may have either been priest/esses, had a priest/essly function, or may simply have been especially enthusiastic devotees; for example, volunteers who helped maintain the sanctuaries and participated in the rites.

Or they may have been members of religious associations that were connected with the sanctuaries and served both a religious and social function. We know of one such group in particular that was connected to one of the Isis-Sarapis sanctuaries on Delos. It seems likely that enthusiasts would be members, or even founders, of such associations.

People could also stay for a time at the temples. In Apuleius’ tale of initiation into Isis’ Mysteries, prior to deciding to be initiated, his character Lucius simply spends time in Isis’ sanctuary:

I took a room in the temple precincts, and set up house there, and though serving the Goddess as layman only, as yet, I was a constant companion of the priests and a loyal devotee of the Great Deity.

Apuleius, the Golden Ass, Book XI, 19

I wish he had described what specific things he, as a layperson, was allowed to do to serve the Goddess. He does describe, in part, the morning rites to which the public seems to have been welcomed:

I waited for the doors of the shrine to open. The bright white sanctuary curtains were drawn, and we prayed to the august face of the Goddess, as a priest made his ritual rounds of the temple altars, praying and sprinkling water in libation from a chalice filled from a spring within the walls. When the service was finally complete, at the first hour of the day, just as the worshipers with loud cries were greeting the dawn light…

Apuleius, the Golden Ass, Book XI, 20

From the evidence we have from Greek Isis sanctuaries, it seems that the Greeks used priest/essly titles they were familiar with, but with adaptations to fit Isis’ mythos. We have records of a hiereus, a priest, a stolistes, one who adorns the sacred image of Isis, a zakoros, an attendant, a kleidouchos, a key bearer, and a melanophoros, a bearer (or wearer) of the black garments—Isis’ black garments of mourning. We can expect that Isis received offerings of food and drink, as did native Greek Deities.

We have mentions from several Roman writers about devotions to Isis. The poets Propertius and Tibullus complain of the period of sexual abstinence their mistresses undertook for Isis. Ovid writes of the crowds of penitents at the temple of Isis. Tibullus also mentions a ritual called votivas reddere voces in which devotees could join in the singing of the virtues (aretai) of Isis in front of Her temple twice a day. (I wonder if they used any of the aretalogies of Isis we know of.)

Interestingly, when Isis comes to Rome, Her Roman worshipers seemed to have tried to make Her worship more “Egyptian” than did Her Greek worshipers. For instance, Roman Isis temples celebrated the rising of Sothis. They added back Egyptian symbols, such as the divine animals: crocodile, baboon, and canine. We see the development of lifelong priesthoods, something done in Egypt, but not done in Greece. Some Roman emperors may have especially appreciated the Egyptian relationship between Isis the Throne and the pharaoh. And it is in Italy that we first see priestesses of Isis rather than just priests.

For modern devotees, knowing the ways in which our spiritual ancestors—whether in Her homeland of Egypt or outside of its borders— honored Isis can inspire us in developing our own ways to honor Her. Whether we make offerings of food upon Her altar, pour libations of milk and wine, or sing of Her virtues before our shrines, we honor the Goddess Who fills our hearts and we connect with those who have gone before us.

Egypt is a land of bricks. From the ancient sun-dried mudbrick temple enclosures to modern Egyptian apartments, everything was and is made of bricks. (And, modernly, supplemented by concrete.)

It’s because there never were many trees and the native ones aren’t very suitable for large building projects. Even anciently, building wood was imported.

So bricks were and are still the answer. the ancient Egyptians encountered bricks on the way into life, during life, and on the way out of life.

The ones they encountered on the way into and out of life were special. There were magical.

On the way into life, there were four bricks, stacked in pairs, that served to elevate a birthing mother so that when her child emerged beneath her, the baby could easily be caught in the hands of the midwife. (According to midwives even today, a squatting or sitting posture is preferable to the supine position in which most modern Western women give birth, generally resulting in a faster, easier delivery.)

On the way out of life, there were the four talismanic bricks that were placed in niches in the four sides of a burial chamber. These bricks were decorated with amuletic figures: in the east, the Anubis jackel; in the south, a flame; in the west, the djed pillar of Osiris; and in the north, a mummiform male figure. All of them protected the deceased.

Doubtless, the talismanic bricks that surrounded the body of the deceased in the tomb were meant to assist in rebirth into the next life, just as the birthing bricks assisted in a child’s birth into physical life.

The Goddess most closely associated with the birthing bricks is Meskhenet, Protectress of the Birthing Place. The bricks were called meskhenut (pl.) after Her. Meskhenet is depicted either as a woman-headed birthing brick or as a woman with a distinctive curling headdress that has been identified as a stylized cow’s uterus. She protects mother and child during the dangerous process of birth, She foretells the child’s destiny as the baby is born, and She is among the Deities of rebirth Who witness the judgment of the deceased in the Otherworld.

With Isis’ own connection to both birth and rebirth, you will probably not be surprised to learn that Isis is closely associated with Meskhenet. At Osiris’ temple complex at Abydos, four Meskhenets serve as assistants to Isis in the great work of rebirth done there. At Hathor’s temple complex at Denderah, a combined form of Isis and Meskhenet (Meskhenet Noferet Iset or Meskhenet the Beautiful Isis) is one of the four Birth Goddesses of Denderah. And in the famous story of the birth of three kings found in the Westcar papyrus, both Isis and Meskhenet are among the four Goddesses Who assist in the kings’ births.

Both tomb bricks and birthing bricks were protective. In an inscription from the temple at Esna, Khnum, the God Who forms the child’s body and ka on His Divine potter’s wheel, places four Meskhenet Goddesses around each of His various forms “to repel the designs of evil by incantations.” As Birth Goddess, Meskhenet is associated with the ka as well. A papyrus in Berlin invokes Her to “make ka for this child, which is in the womb of this woman!”

We have a few surviving spells that were used to charge the birthing bricks. They were used to repel the attacks of enemies to the north and south of Egypt and may indicate that the birthing bricks, like the tomb bricks, were connected with the directions.

And here’s another tidbit showing parallels between the magical tomb bricks and birthing bricks. In an Egypt Exploration Society article by Ann Macy Roth and Catherine H. Roehrig, the authors point out an interesting gender-reversed aspect of these magical bricks.

You may recall that four Sons of Horus are the Gods Who protect the four canopic jars that contain the internal organs of the mummy. These four Gods are, in turn, guarded by four Goddesses. In Tutankhamun’s tomb, the Goddesses are Isis, Nephthys, Selket, and Neith. Roth and Roehrig suggest that we may be able to explain the amuletic figures associated with the tomb bricks in a similar, though opposite, manner. If the four meskhenets are personified as four Goddesses Who protect the birthing place, perhaps the four figures on the tomb bricks—the God Anubis, a mummiform male, a Divine pillar associated with Osiris, and a flame, the hieroglyph for which is rather phallic—may be considered Divine Masculine Powers Who protect the four Meskhenet Goddesses, just as four Goddesses protect the four Sons of Horus.

It is worth noting that these magical bricks were made in the same way as were the traditional mudbricks of Egypt. They were fashioned from the fertile Nile clay and sand, mixed with straw, which may be associated with Isis as Lady of the Fertile Earth, then they were dried in the brilliant heat of Isis-Re, the Radiant Sun Goddess. And, of course, as a Divine Mother Herself, Isis is connected with every aspect of human and animal fertility, from conception to birth, as well as the protection of the children as they grow.

As we have a south-to-north flowing river here in Portland, I might see if I can get some Portland “Nile” mud to create four miniature mudbricks. Then I could magically charge them by naming them “Meskhenet Noferet Iset” and placing them in the four quarters of the temple—or even outside, one on each side of the house. They might provide some very fine magical protection.

I often find it easier to keep up my spiritual practice when I have something “set,” something specific, to do. Like a small ritual that I’ve pretty much got memorized. Is that true for you? If so, then today I’d like to share with you just such a small ritual. This one is an offering rite. It is adapted from the Daily Ritual in the Egyptian temples. (If you have your new copy of Offering to Isis, a version of it is in there. Here’s a version you can use, and of course, adapt, as you choose.)

I’ve called this one the Adma Iset, “Offering to Isis.” Adma is one of the (many) Egyptian words for an offering rite. I preferred the sound of this one compared to some of the others, so I adopted it. Based on Egyptian temple rites, this ritual is adapted for a single person instead of a temple-full of folks.

The Adma Iset

Ritual Tools: A cup or other vessel of pure water; a censer with charcoal and incense; fire starter for incense; an offering (this can be anything you choose: milk, beer, flowers, a poem, a dance); a small reed mat (such as a table place mat); a shallow tray of sand large enough to place one foot in; a bundle of fresh plants for sweeping the sand. These last two are optional, but are adapted from things they actually did in Egyptian temples. You can do this rite at your altar; I will assume you have a sacred image of Isis on your altar.

Ritual Preparation: Prepare your offering as needed; set the small reed mat on the floor before the altar; place the tray with sand and the fresh plants conveniently to the side.

Purification & Consecration

Sit comfortably before your altar, breathing slowly, clearing your mind. When you are ready, rise, approach the altar of Isis, and bow politely.

Ritualist: (Raising your hands in a gesture of adoration) Isis is all things and all things are Isis.

Take up the cup and elevate it.

Ritualist: (To the Purifying Powers) O, You Souls of Night, Water Dwellers, Purifiers, You of the Pure Water from the Sycamore Tree of Isis, I have come for you. By the Blood, by the Power, by the Magic of Isis, establish yourselves within this vessel!

Lower the cup to heart level. Visualize blue light coming into your body from above, let it move through your body into the earth, then bring it back up into your heart, then into the cup as you vibrate.

Ritualist: (Vibrating) ISET MU [EE-set MOO; Egyptian: “Isis of Water”]!

Circle your ritual space, sprinkling water, then sprinkle yourself.

Ritualist: (Speaking while walking) Isis is pure. The temple is pure. The temple is pure. I am pure. I am pure with the Purity of Isis. I am pure with the Purity of the Goddess. (Repeating until you return to the altar; then repeat as needed until you feel the truth of your statement.)

Ritualist: By the Magic of Isis, it is so!

Return cup to altar, take up censer and elevate it.

Ritualist: (To the Consecrating Powers) O, You Souls of Day, Fire Dwellers, Consecrators, You of the Pure Breath from the Mouth of Isis, I have come for you. By the Blood, by the Power, by the Magic of Isis, establish yourselves within this censer!

Lower the censer to heart level. Visualize red light coming into your body from above, let it move through your body into the earth, then bring it back up into your heart, then into the censer as you vibrate.

Ritualist: (Vibrating) ISET ASH [EE-set AHshh; Egyptian: “Isis of Fire”]!

Circle your ritual space, censing it and then yourself.

Ritualist: (Speaking while walking) Isis is consecrated. The temple is consecrated. The temple is consecrated. I am consecrated. I am consecrated with the Fire of Isis. I am consecrated with the Flame of the Goddess. (Repeating until you return to the altar; then repeat as needed until you feel the truth of your statement.)

Ritualist: By the Magic of Isis, it is so!

Entering

Face the altar and make the Gesture of Adoration.

Ritualist: Isis is upon Her Throne. The spirits awaken! They awaken in peace for they know that I have come to make offering unto this Great Goddess.

Put your palms together and extend your arms straight out in front of you. Slowly open your arms as if opening a heavy curtain. This is the gesture of Opening the Shrine. Place the tray of sand before the sacred image and step in it to leave a footprint in the sand.

Ritualist: The sacred doors are opened to me. The light goes forth. It guides me on a fair path to the place where the Great Goddess is. I approach Your shrine, O Isis.

Offering to the Uraeus Goddess

Take up the censer and elevate it.

Ritualist: (Addressing the Uraeus serpent form of Isis) The Sacred Eye is powerful. Lady of Flame, Great One Who is between the horns of the Sunshine Goddess, accept this perfume and let me enter in peace.

Place the censer in your dominant hand, resting on your upturned palm. Bring that hand to your heart. Breathe in and visualize light glowing around the censer. Slowly swing your arm outward toward the image of the Goddess. Visualize the light flowing from the incense smoke to Her sacred image. This is the Gesture of Giving. Return the censer to its place.

Invoking the Goddess

Stand before the sacred image. Place your palms together in front of you as if preparing to applaud. Bring them apart to a comfortable distance, remaining thumbs up. To make the Gesture of Invocation, move the tips of your fingers towards you in a ‘come to me’ gesture. Do this slowly and gently as you speak the invocation below.

Ritualist: Iu en-i. Iu en-i (Eeoou-en-EE; Egyptian: “Come to me”). Come to me, come to me, Beautiful, Great One—Isis of Many Names, Great of Magic, Great Mother, Great Goddess. Come to me, come to me! (Vibrating) ISIS. ISIS. ISIS.

See within your heart the light of the Goddess. Feel it glowing with sun-bright warmth and beauty.

(Speaking to the Goddess) Fair is Your coming to Your temple, Isis. Beautiful is Your appearance in my heart.

Place your hand upon your heart, breathe in, and on the out-breath, move your hand toward the altar and send that light into the sacred image of Isis.

Making Offering

You may continue to stand or be seated at this time.

Ritualist: My body being on Earth, my heart being awake, my magic being in my mouth, O Isis, I make offering unto You.

Take up your offering. With open heart, speak aloud why you have chosen to give that particular offering for the Goddess.

If your offering is physical, use the Gesture of Giving (above) to offer it to Isis. If it is not, visualize a symbol representing it in your palm as if it were physical. Breathe in, visualize light around the offering, then on the out-breath, move your hand toward the altar and see that light transfer to the sacred image of Isis. Then, if your offering is performative, perform the offering (e.g. read the poem, dance the dance).

The Reversion of Offerings (optional section)

Standing, make the Gesture of Adoration toward the sacred image of Isis. Close your eyes and visualize the Goddess tracing an ankh symbol over the offering you have given. It glows with the power of Life, the power of Her Divine Ka. She breathes a blessing into it. She breathes a blessing into you. Breathe Her breath and be blessed.

Ritualist: The offering is reverted. Its blessing comes to me. Its blessing goes out into the world. Its beauty endures forever.

Note: Offerings such as food and drink, once reverted, may be consumed by you and your household. Non-consumable offerings may be kept on Isis’ altar or kept in some other convenient place nearby.

Closing the Temple

Once again, take some time to see the light of what you have given glowing around the sacred image of Isis. Let yourself know that She has accepted your offering. Feel Her blessing upon you in return.

When you are ready, take up the bundle of plants and sweep away the footprint in the sand. Make the Gesture of the Closing of the Shrine (the opposite of Opening the Shrine above).

Ritualist: I have flourished on water. I have grown on incense. I have climbed up on sunbeams. O Isis, give me Your hand for I have made offering unto You.

Be in peace, Isis, be in peace. Amma, Iset (AH-ma, EE-set; Egyptian: “Grant that it be so, Isis”).

The Adma is finished. Exit the ritual space or remain in meditation as desired.

More from the Temple of Isis at Dendera.

In this one small, mostly destroyed temple, there are many Deities speaking.

They are everywhere, on every wall. Many are well known, like Tefnut and Hathor and Thoth; some more obscure. The king—always said to be beloved of Isis and Ptah—is ubiquitous as well as he makes many different offerings of many different kinds. And, as this is the temple of the birth of Isis, She Who is First Born Among the Goddesses, there is much rejoicing in this small temple.

For example, the Goddess Merit, the Enchantress Who is here called “Lady of the Throat,” uses Her beautiful throat and voice to arouse joy and bring intoxication; She also leads the dances for Isis. Isis Herself is Mistress of Intoxication Who Arouses joy, Whose Heart is Satisfied with Revelry. Nuet declares that She “makes every person rejoice to see You [Isis].” Hor-Ihy, a combination of Isis’ son Horus with Hathor’s son Ihy, plays the sistrum “for the Mistress of the Sistrum-Temple, Isis the Great, Mother of the God.” The Gods dance for Her. The Goddesses are joyful for Her. The women play the tambourine for Isis the Luminous One. Hathor, Mistress of the Sweet Breath, sings for Her.

A lot of what we find in this temple, as we did in Hathor’s, are the various names of the Goddess Isis in other parts of Egypt. Interestingly, an inscription on this temple is also one source for our understanding of the Goddess Bast (or Bastet) as “the soul of Isis.” It comes from one of those inscriptions where Isis is being described as a Goddess of various names in other Egyptian locales. And one of those names is

“Nbt B3st (Lady Bast or the Lady of Bubastis) is the Heliopolitan. B3 n 3st [ba or “soul” of Isis] it is said of Her name. B3t is Her name in the mouths of human beings from ancient times of the Deities until now.”

We can be pretty sure that the Egyptians were engaging in some word play here—word play that is intended to reveal mysteries. If you look at the transliteration (writing the hieroglyphs in “latin” or “roman” letters; with the addition of some special characters) of Bast’s name and Isis’ name, you will see that the letters for Isis are within the name of Bast: B3st and 3st. The “3” here does not really represent a three, but is one of those special characters; it is sometimes called aleph, from Hebrew, because it is a consonant that is also “sort of” a vowel, as aleph is in Hebrew. For simplicity’s sake, we are usually told to pronounce it like an English long “a,” (ah). But it isn’t really an a. It’s a glottal stop. Here’s how that works in Isis’ Egyptian name.

So, what the Egyptians were telling us is that Bast and Isis are linked because from within the name Bast, Isis is revealed. This is expressed by writing that B3 n 3st [Ba/soul of Isis] it is said of Her name.” But “ba” in Egypt isn’t really what we usually mean by “soul” though that is a conventional translation. The concept of the ba is much, much more complicated—and I’ll post on that sometime, but not today.

But in short, ba is one way that a Deity can express Themselves. Ba is an active manifestation of a Deity. So a better way to think about it would be that Bast can be a manifestation of Isis. Or that Isis can express Herself as Bast. This is very much in line with the very fluid way Egyptian Deities can flow into or become each other or express Themselves as each other.

In the final line of this section of the inscription, it says B3t, or Baet, is Her—in this case, Isis’—name “from ancient times of the Deities until now.” This is not a reference to the Cow Goddess Bat or Ba-et. Instead, it is an expression of Isis’ immense power. The ba-power of a Deity made manifest is often written in the plural, bau, though often treated as a singular. The plurality not only intensifies the power, but also recognizes that the Deity is not limited to a single manifestation of power. For example, wind is the bau of Shu. The stars are the bau of Nuet. And both have other bau as well.

Thus to be the Goddess Baet, Whose very Name—from ancient times until now—IS this ba-power, is to be powerful indeed. We learn about Isis’ bau in other inscriptions at Dendera as well. She is said to be the One “Whose bau is great.” In fact, “Her bau is greater than all the Gods.” As a Baet Goddess, She shares this great might with only few other Goddesses, such as Hathor, Neith, and Nephthys. As a Baet Goddess, She shows Her power on earth, where humankind bows to it, and in the heavens, where She is B3t em pt, the Mighty One in the Sky.

On another wall of Her temple, at least a dozen Deities “open the New Year” for the Daughter of Nuet, Isis the Goddess. We even have the founding date for the current temple: July 16, 54 BCE. That was the day of the heliacal rising of the Star of Isis, Sirius, and—the temple records—that for a brief time that morning, both moon and sun were seen in the sky. So both Re and Osiris were there to greet Isis at the foundation of Her Horizon or Akhet Temple. It is so called, no doubt, due to its orientation to the east and the rising of Her Star, as well as the regenerative power of the liminal space of the Akhet.

We also learn that,

“On this beautiful day, the Day of the Child in His Nest, [there is] a great festival throughout the country, Isis is given birth at Dendera by Thoueris [meaning the Great One, in this case, Her mother Nuet] in the temple of the Venerable [Isis].”

And that Isis was born as

“a woman with black (kemet) hair and red (desheret) skin, full of life, Whose love is sweet.”

This must also be word play, for Isis is born with the colors of the Black Land and Red Land shown forth in Her Divine form and so She rules over both; She rules over all things.

Indeed, even from before Her birth, Isis was destined to rule.

“Destiny distinguishes Her on the birthstones. Her heart is rich in all virtue. The south is given to Her until [that is, “as far as”] the [place of the] rising of the Disk, the north until the limits of Darkness. She is mistress of the sanctuaries of Egypt with Her son and Her brother Osiris.”

Isis is Queen of Upper and Lower Egypt and She rules the Two Lands “from the bricks of birth.” She is the ruler of cities and sanctuaries; indeed She is the Venerable One Without Equal, the Regent Who Governs the Universe.

Just as Isis’ own birth is celebrated in this temple, so Her birth-giving to Horus is also celebrated. Isis is called “the Primordial, the First to Give Birth Among the Goddesses, the One with the Beautiful Face, Whose Milk is Sweet.”

I’ve just scratched the surface here. There’s definitely more. Next time, we’ll look into some of the birth-associated texts and images to see what we can learn there.

I (almost) have my author copies of Offering to Isis! It’s been a long time coming, but it’s finally here.

The shipment is on the way from the printer to the publisher even as you read this. So, if you pre-ordered a copy, it should be on its way to you soon. If you’d like to order a copy, it’s available from Azoth Press at the Miskatonic Books website. Here’s the direct link.

I’ll do an unboxing video when I get my copies to show you more of the book. But in the meantime, here are some pics from the publisher:

I know a lot of you are familiar with Isis Magic, but maybe you haven’t yet come across Offering to Isis. I may be a bit partial, but I really like this book a lot, too.

Offering to Isis is about how we can connect with, honor, and grow our relationship with Isis through the ancient and eternal practice of making offering. Offering is one of the most important ways we human beings have always communicated with our Deities. It was vitally important in ancient Egypt and it’s just as important for those of us interested in or devoted to Isis today.

If you’ve ever wondered exactly what sort of things to offer to Isis, Offering to Isis includes in-depth explanations of 72 sacred symbols associated with Isis—symbols that make ideal offerings to Her.

We’ll also talk about the how and why of Egyptian offering practices, including the important and genuinely ancient Egyptian technique of “Invocation Offering.”

There’s information on exactly how the ka energy inherent in every offering is given to and received by Isis—and what to do with offerings once they’ve been received. You’ll also find a selection of offering rituals, from simple to complex, for a variety of purposes. Most rites are for solitary devotees, so I think you’ll find one that works just right for you.

If you’re curious and want to know exactly what’s in the book, you can download a PDF copy of the full Table of Contents by clicking on the caption under the “Contents” image.

The largest section of the book details the 72 sacred symbols of Isis. You’ll add to your knowledge of Isis and Her ancient worship by learning more about Her through Her important sacred symbols. You’ll see how each one is intimately connected with Her and how they may be used in offering rites for Her. Every entry also includes an Invocation Offering that you can use for your own offerings to Isis.

One of the things I especially like about this book is that you can just open it at random and you’ll likely find something you hadn’t known about Her, something that I hope will inspire you in your own devotions. For instance, how did the Knot of Isis come to be Her knot? What stones are associated with Her? What animals are connected with Her? Why are dreams especially important when it comes to Isis?

As it’s been a few years since this book was first published, the text has been thoroughly updated. All the hieroglyphs associated with the offerings have been re-illustrated and are much more accurate—and much more beautiful—in this new edition, too. There’s also a handy appendix in the back for quick reference in finding any offering you may need.

This new Azoth Press edition can be purchased only through the Miskatonic Books website. (If you go to Amazon, you will be ordering a 20-year-old paperback edition published by Llewellyn in 2005, which people are trying to sell at very inflated prices.)

Oh yes, and if you’d like, you can take advantage of Miskatonic’s installment plan that lets you pay over several months so it doesn’t take a big bite out of your budget. Plus, the new hardback edition is priced A LOT lower than those overpriced, out-of-print first editions that I’ve seen out there.

When you go to the Miskatonic site, you’ll find two different Azoth Press Offering to Isis editions. For the high rollers, there will be 36 copies in a gorgeous leather-bound and numbered collector’s edition. For the rest of us, there will be 650 numbered, limited edition copies in a cloth-bound hardcover. Both editions are two-color throughout, and more than 400 pages.

Thank you so much for letting me interrupt our regularly scheduled blog post to tell you about this new edition. And would you please do me a favor and share this information with anyone who you think might be interested? Feel free to ask me any questions about Offering to Isis that you’d like, too.

I’m definitely looking forward to getting my copy of this beautiful, new edition of Offering to Isis.

And while you might think it’s strange, even though I wrote the book, I still use it for reference when I’m making offering to Isis. I use the information in it as well as the Invocation Offerings. I hope this new edition will serve you well, too.

I finally got my interlibrary loan of Egyptologist Silvie Cauville’s Dendara: Le temple d’Isis. And the minute I starting perusing this two-volume set, I knew I wanted to own a copy. So Adam got it for me for my birthday. Yippee!

So now I get to tell you what I’ve been learning.

The first thing to know is that, just as Isis is very present in Hathor’s great temple, so Hathor is present in Isis’ smaller Dendera temple.

And, as with many of Egypt’s temples, the current remains sit atop older structures. What we see today at Hathor’s temple is mainly Ptolemaic, while the bulk of what remains of Isis’ temple was constructed under the Ptolemies but completed and decorated during Augustus’ Roman rule.

Hathor’s worship at Dendera is much more ancient than the Ptolemaic period. There is evidence of a temple there from about 2250 BCE, during the reign of Pepi I. There’s also evidence of an 18th-dynasty temple. The Isis temple has earlier roots, too. There are vestiges of structures from the dynastic reigns of Amenemhat I (1991-1962 BCE), Thutmose III (1479-1425 BCE), and Rameses II (1279-1213 BCE). During the reign of Nectanebo I, the temple of Isis served as a mammisi for Isis as She births Horus.

One of the interesting things about the temple of Isis at Dendera is that, due to its older substructures, its current configuration has two main axes: east-west and north-south. Thus the temple opens to all four directions. The main temple entrance and hypostyle hall align with the heliacal rising in the eastern sky of the star of Isis. Sirius’ rising marked the coming of the Inundation and initiated the Egyptian New Year. Opposite, in the west, is the point of descent for Isis’ beloved, Osiris Lord of the Westerners. The north-south axis is marked by carved Hathor heads and connects that Goddess with Her father Re at Heliopolis to the north and with Her spouse Horus at Edfu to the south.

Blocks from the mammisi of Nectanebo’s time were reused in the Ptolemaic/Augustan temple that we see the remains of today. This temple celebrates the birth of Isis Herself. Her mother Nuet births Her Great Daughter upon the primal Birth Mound, the First Earth. The temple (you will sometimes see it called the Iseum) also celebrates the sovereignty of Isis.

Here then, the Goddess Whose name means “Throne” is the guardian of the throne of Egypt, protectress of the king, and is Herself the regent of all of Egypt. Her Dendera temple is also the place of Her coronation as Divine Queen of the Universe. To me, this universal rulership of Isis is echoed by the temple’s four-directional doorways. Her ruling energy radiates from Her temple out to every corner of the world, if you will. And, if you recall, we learned several weeks ago that Isis’ rulership is so potent that She ruled the Two Lands even even before She was born, from within Her Great Mother’s womb.

Dendera’s temple of Isis consists of three main chambers, the Per Wer, “Great House,” the Per Nu, “House of Water,” and the Per Neser, “House of Fire.” These chambers are also found in the Hathor temple, along the north-south axis. I was familiar with the Per Nu, the water sanctuary, but the fire sanctuary—the Per Neser—was new to me. There is also an offering vestibule in front of these chambers.

It pleases me no end that in our own home shrines and altars, we can easily replicate this ancient Egyptian temple structure.

The altar is our Per Wer, where the sacred image or images of our Divine Ones live and receive offerings. The Per Nu is where our purifying and libation waters, cups, and other vessels are placed (mine is to the left of the altar). The Per Neser is where the candles, incense, charcoal, and lighters are kept (right side for me). My collection of sistra is also on the Per Neser side. In the House of Isis (see Isis Magic), the sistrum corresponds to Fire because of its ability to “shake things up.” In Egyptian, to “play the sistrum” is iri sakhem, “to do power.” The sistrum is thus an energy generator; very fiery.

I love all this so much that I fully intend to call these parts of Her shrine by these names from here on out.

Since there is so little left of this temple, that about wraps up our tour of the building itself. Next time, I’ll be looking into the inscriptions to see if I can find any new and interesting epithets or lore of the Goddess that I can share with you.

What about you? Do you have a special place near your altar that serves as your Per Nu and Per Neser?

This is a longish post because I found out some things I didn’t know about the Kite, the Kites, and Isis and Nephthys as the Kites. I’ll bet you’ll find out something you didn’t know, too.

Now, what you may already know is that the most consistent avian form that Isis and Nephthys take is the black kite. Black kites are birds of prey. They eat carrion and they hunt live prey. And one of the things I just learned is why they are called “kites.” It’s from their characteristic hunting technique in which they hover over the prey (like a paper kite does at the end of its string) and then do a swift dive to capture it. This highly successful hunting move is called “kiting.”

So today, we’re looking into the Kites, especially (but not exclusively) the Divine Kites, the Goddess Kites. We often see Them as Isis and Nephthys at the head and foot of Osiris’ mummy bier. Sometimes They are in Their bird form, sometimes fully anthropomorphic, and sometimes combining the two forms as women with wings.

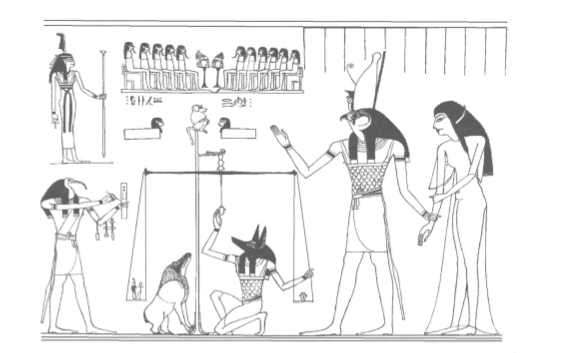

In other images, we see Isis as a kite hovering (kiting!) over the erect phallus of a mummyform Osiris in order to conceive Their child Horus. We also find the Kite/s in funerary processions and in the Opening of the Mouth ritual. The Opening of the Mouth is a funerary rite; its main purpose is enlivening. It was used to give life or renewed life to everyone and everything from the mummified king to the sacred statues and images in a temple.

Egyptologist Racheli Shalomi-Hen notes that the first appearance of a Kite or Kites is in depictions of non-royal funerary processions of the late 5th dynasty of Egypt’s Old Kingdom. We know who the Kites are in these depictions because they are labeled. In Egyptian, Kite is Djeret while the Two Kites are the Djereti.

Egyptologists usually group the Kite/s in with other professional mourners (as opposed to mourners from the family of the deceased). This is probably because, once the Kites were connected with Isis and Nephthys, They were mourning Osiris. But the Kites seem to have other functions as well.

If the Kites were professionals, it must mean that their roles required special knowledge and skills. Just speculating here, but I wonder whether they were specialized priestesses of some kind. (As an aside, the Kites were also associated with another special funerary ritualist, the Demdjet. You can read about the Demdjet here.)

Shalomi-Hen suggests that the appearance of the Kite/s in these non-royal tombs is an indication that the non-royal dead were already identified with Osiris by that time—earlier that usually thought. At that time, she says, the Kites were not associated with the Goddesses; they were human funerary ritualists.

She proposes that it was only after the king wanted to be an Osiris, too, that the Kites gained Divine and mythological status—and that this was done for the first time in the Pyramid Texts.

Other Egyptologists think that the basic Egyptian myth cycles, including the Osirian, may have been formed as early as the 2nd or 3rd dynasties—though we have nothing of length written down until the Pyramid Texts.

I’m not convinced that the Osirian myth we find in the Pyramid Texts represents the first time that this myth cycle was formulated. In the Pyramid Texts, we already see the characteristic mythological allusions that assume that scribes and educated readers (such as the priesthood concerned with funerary rites) would understand the reference to the whole myth from just the allusion. If this were the first time the myth was formulated, they would not have been able to do so. Instead, this must mean that—even before such allusions were written down in the Pyramid Texts—there was an oral tradition, and that is where the Osirian cycle first emerged.

In the illustration from one of these non-royal funerals (above), you can see that there isn’t anything particularly bird-like in the Kite’s dress or implements; indeed she has no implements and wears only the usual Old Kingdom sheath dress. Yet she is called the Kite. What then is the connection between the black kite and funeral rites?

Some scholars have suggested that the cry of the black kite may have sounded to the Egyptians like mourning women. I’ve listened to a number of recordings of black kite calls and…maybe? The closest one I’ve found is the warbling call in the last part of this video. The wavering cry sounds vaguely mournful. On the other hand, the kite also has a sharp cry, which caused another Egyptologist to suggest that the kite’s cry might have been thought to wake the dead. Yet another offers that the kite’s participation in funerals may have developed from a prehistoric hunting ritual. I wanted to look into that a bit, so I dug up that article.

In it, Egyptologist Eberhard Otto notes that the Kite is also present in some versions of the Opening of the Mouth ritual—in the part where the foreleg of the bull/bull calf is being cut off and its heart cut out. Sometimes, this female ritualist is identified simply as the Kite or the Great Kite. Sometimes there are two ritualists, the Great Kite and the Small Kite, Who later were identified with Isis and Nephthys.

In versions of the ritual where the Kite is present, she/She whispers into the ear of the sacrificial animal, blaming it for its own death. She says, “Your two lips have done that against you.”

Egyptologist Maria Valdesogo Martín identifies the Kite in the New Kingdom scene from the Opening of the Mouth shown here specifically as a mourner. This would be consistent with the well-known functions of the Kite at that time—as well as with the identification of the Great Kite as Isis. And mourning the slain animal is certainly an improvement over victim-blaming.

Nonetheless, this incident did remind me of the myth of the Contendings of Horus and Set in which Isis, in disguise as a maiden-in-distress, tricks Set into admitting that Osiris’ kingdom should go to Horus. Significantly, She first transforms into a kite, then flies into a tree and screeches, “Ha! Your own words have condemned You!”

Otto thinks that the Opening of the Mouth scene with the Kite is the part that may have originated in a prehistoric hunting ritual. He says the Kite is a later representation of a wild kite circling the body of a slain animal. The shrieking cries of the bird may have been interpreted as speech—which in later periods developed into the Kite blaming the animal for its death and, eventually, to mourning.

We begin to see Two Kites rather than just one in depictions of private funerary processions during the 5th dynasty, with most in the 6th dynasty. In the Pyramid Texts of the 5th and 6th dynasties, decidedly royal texts, we learn that the “Djereti of Osiris,” Who can only be Isis and Nephthys, “remove the ill” from the king as part of the preparation for his ascent to the heavens. In other words, They purify the king. What the Kites are removing is said to be poison, which is envisioned as venom from the fangs of a serpent that pours into the ground as the Kites supervise the action.

The Kites also help ferry the deceased king, as Osiris, “across the Winding Waterway” to the Horizon (Akhet) and rebirth. In tomb chapels of the same period as the Pyramid Texts, Kites are shown at the bow and stern of a boat that carries the coffin. We know that they/They are mourning for they/They make known mourning gestures in some cases and protective gestures in others. In these tomb chapels, the Djereti may or may not be identified as Isis and Nephthys.

We also find the Djereti represented on model boats since the Kites ferry the dead to rebirth. And here’s something really interesting.

One model boat from the Middle Kingdom includes the names of the Goddesses preceding what seem to be personal names. We see “the Nephthys Hotep-Hathor, justified” and “the Isis Hetpet, justified.” When a human name is followed by maakheru or “justified,” it means that the person is dead and has passed the judgment of Osiris. Perhaps what we are seeing here is previously deceased female relatives of the newly dead person serving as Isis and Nephthys for the deceased to help their loved one cross the Winding Waterway to rebirth.

In addition, the Kites were sometimes connected with the mummy wrappings. The Goddess of Weaving, Tayet, is sometimes identified as a Kite. Isis and Nephthys, known as the Two Weavers, are also Weaving Goddesses. There are a few Old Kingdom reliefs and paintings that show pairs of women labeled as Kites carrying boxes of offerings on their heads. In one example, we learn that they are “bringing khenit-cloth.” Khenit means “yellow” and yellow is the same as gold in Egyptian color symbolism. Thus, this cloth is solar and refers to the daily solar resurrection. Here again, we have the Kites assisting in rebirth. These cloth-bringing Djereti also sometimes have personal names attached to them, indicating that they are human Kites.

By removing poisons, attending to the mummy wrappings, and bringing offerings of yellow cloth, the Kites surely were part of the magical and physical preparation of the body and the tomb, just as female relatives were and are in so many societies, ancient and modern. Perhaps the professional Kites even guided or assisted the relatives of the deceased in these tasks.

Yet so far—with the exception of the kite’s cry interpreted as speech to the sacrificial victim or the possibility that their raptor-cries sounded like mourning—there doesn’t seem to be anything very kite-like or bird-like in the funerary function of the Kites.

But then there are those wings. Those bird wings, those kite wings.

The wings of Isis and Nephthys are Their most obvious avian attributes. As birds, the Kites fly; as birds of prey, They hunt.

As far back as the Pyramid Texts, the Two Sisters are the ones Who seek—or hunt for—Their missing brother Osiris. Their wings give Them the power to search a vast territory in a shorter period of time. Their lofty vantage point and sharp birds-of-prey vision make Them successful in their hunt.

In the Pyramid Texts, Osiris has not been dismembered, only killed. Yet when His dismemberment does become part of the myth, it isn’t much of a stretch to imagine the carrion-bird Sisters scavenging for the parts of the God’s body to re-assemble Him and make Him whole.

In the Hymn to Osiris in the Book of the Dead, Isis uses Her wings to revive Osiris enough so that She can conceive Their child and heir. “She made light with Her feathers, She created air with Her wings, and She uttered the death wail for Her brother. She raised up the inactive members of Him whose heart was still, She drew from Him His essence, She made an heir…” the text tells us.

In Egyptian lore, wings are also protective. Many are the Goddesses, wings outspread, Who protect tombs, sarcophagi, doorways, and temples. There are also a number of surviving statues of a larger Isis with a smaller image of Osiris protected between Her wings.

I remain on the lookout for more about the Kite Goddesses (as well as the human Kites). But for now we can know that Their wings are protective, Their cry can be mournful or accusatory, Their wings and vision make Them successful hunters and searchers, They can purify and prepare the dead for resurrection, and They can help “ferry” the dead toward the Horizon of Rebirth.

We learned several weeks ago that one of the things said of Isis at Denderah is, “Life is in Her hand, health is in Her fist, one does not oppose what comes from Her mouth.” But was H. Rider Haggard’s Ayesha—of “She Who Must Be Obeyed” fame—based on Isis and/or Isis-connected literary characters?

Let’s see what we can find out.

First, who is Ayesha? Well, unless you are a fan of Victorian gothic novels or the British TV show Rumpole of the Bailey, you may not have heard of her.* Ayesha is the title character in the novel She: A History of Adventure by the English writer H. Rider Haggard. Haggard wrote adventure-romances set in exotic locations, mainly Africa, inspired by his having lived there for six years.

Along with King Solomon’s Mines, which introduced the character Allan Quartermain, She is Haggard’s most renowned work. It was enormously popular. First published in 1887, it has never been out of print and has sold over 100 million copies. Haggard was one of the innovators of the “lost world” genre and She is a classic example of that genre.

Ayesha is the mysterious “white queen” (I know, cringe) of an equally mysterious tribe living in the African interior. Ayesha is worshiped by her people as Hiya, She Who Must Be Obeyed, or simply She.

The novel has been studied and both praised and criticized for its depictions of female authority and power.

The Victorian and early-Edwardian era was also host to a wide-ranging male preoccupation with the “True Nature of Woman,” and mostly, in their cogitations, Woman’s True Nature tended toward the evil, perverse, and degenerate. This is where all those vampiric fin de siecle femmes fatales that populated a good portion of the art world at that time come from.

“The Woman Question” was much-discussed as the rise of the more-liberated, educated, and independent New Woman terrified the traditionalists. (And why are we still and again having to have this infuriating and exhausting discourse?)

But back to Ayesha.

Ayesha is a powerful sorceress who has discovered the secret of immortality. She’s been waiting 2,000 years for the reincarnation of her lover, who she killed when he refused to murder his wife to be with her. Yes, it’s complicated.

Our heroes, Cambridge professor Horace Holly and his adopted son Leo Vincey, travel to Africa in search of a lost civilization—and find it with Ayesha and her people. When Holly is ushered into her presence, she is veiled and warns him that the sight of her arouses both desire and fear. And this is so, for when she unveils herself, Holly falls to his knees before her, bespelled. Ayesha and her people live in the lost city of Kôr, a city of the people who predated the ancient Egyptians. Ayesha was born among the Arabs and studied the wisdom of the ancients to become a great sorceress.** In deepest Africa, She learned the secret of immortalization in the fiery Pillar of Life.

Ayesha is convinced that Holly’s adopted son is her reincarnated lover. She wants him to step into the Pillar of Life as she did so that he, too, can be immortalized. (Anybody getting Mummy movie vibes?) To prove to him it’s safe, Ayesha makes a fatal mistake, again walking into the burning Pillar herself. With her second exposure, her immortality is reversed and she dies—but with her last breath vows to return! Holly and Leo are freed from her deadly spell and hightail it home to England.

We do have some Isis-themed bits here: a powerful, Goddess-like magician, secret knowledge, immortality, love, sex—all in a lost city more ancient than ancient Egypt. In a sequel to She (of course there was a sequel)—Ayesha: the Return of She—Haggard tells us that Ayesha’s name is to be pronounced “AH-sha” which is slightly reminiscent of Isis’ name in late Egyptian: Ise or Ese. The sequels also include “an ancient sistrum” and a rock formation in the form of an ankh for some clear Egyptian ambiance. Haggard’s novel fits right in with the significant case of Egyptomania Europe was giddily undergoing at the time. Haggard himself was deeply interested in Egypt and wrote another novel, Morning Star, that was set in ancient Egypt and featured a strong-willed Egyptian queen as protagonist.

In an article I’m reading by Steve Vinson, he suggests that some aspects of She, may have come from the tale of Ahwere and the Magic Book, a tale you already know has Isis connections. You’ll find those here and here. In addition to the focus on magic and some name similarities in the two tales, the dramatic power and alluring beauty of Ayesha is similar to the power and allure of Tabubu in Ahwere’s story.

You might also remember Aithiopika, the ancient Greek novel by Heliodorus, that also has Egyptian and Isis connections. Re-read those here. Vinson notes those and other similarities as well. In both novels, there’s an adventure in Africa where the young protagonists discover their true identity. In the case of She, it is Holly’s adopted son Leo who finds out that he actually IS a descendant of Ayesha’s lover, Kallikrates. Kallikrates is Greek and married to the Egyptian Amenartas, a priestess of Isis. The power of Isis protects Amenartas from the wrath of Ayesha when Kallikrates refuses to kill her. Vinson notes some similarities between the stories of Kallikrates and Aithiopika‘s Isis priest Kalisiris, as well as quite a few plot points that indicate the influence of Aithiopika on She. But those mostly don’t concern Isis, so I won’t detail them.

Vinson also finds parallels in the portrayals of Ayesha and other strong female leaders in Haggards’ stories with the character of Isis Herself, as well as with the Isis-connected protagonists in these ancient Egyptian and Greek tales.

Isis was, quite simply, the most well-known Egyptian Goddess in Haggard’s time, and with Her multi-facted nature, it would be hard not to be able to find almost any type of Isis you’d like—from kindly to avenging. Isis embodies sexual power, too; see here and here, though She is not generally portrayed as a Great Seductress. Haggard had to turn to Isis-connected characters like Tabubu and Rhodopis (a courtesan in Aithiopika) for that.

Isis looms large in the Victorian era, with its Woman Question and Egyptomania. Ancient stories like the ones we’re talking about intrigued readers and inspired writers like Haggard and others. Translations of Plutarch’s works, including On Isis and Osiris, made Isis’ story, and Her famous veil, more widely known, while Madame Blavatsky’s opus Isis Unveiled established Her in the occult world.

As far as Europe is concerned, I don’t think it’s too much to say that Isis served as THE prime example of Feminine Divinity during this period. What’s more, as a feminine Being with both power and authority, She served as an inspiration for the New Woman of first-wave feminism. Remember Margaret Fuller?

From the world of the sciences to the arts to the occult, Isis was strongly present. Scientists worked to draw aside Her veil to reveal the secrets of Nature. Artists and writers were inspired by and wrote about Isis and Egypt. Occult groups such as the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, incorporated Her prominently into their magical systems.

If any Goddess was THE Goddess in late-19th-early-20th-century Europe, it was Isis. Indeed, it would be surprising if Haggard’s Ayesha was not inspired by some aspects of the Goddess Who was so well known in his day.

*Ayesha or Aisha is also a wife of the Islamic prophet Mohammad and a well respected figure in Sunni Islam. The name Ayesha was very popular during the Ottoman Empire and it came to symbolize all-things-Arabian to 19th-century English readers. Many English novels and stories featured characters named Ayesha.

**I know. The math don’t quite math with Ayesha being over 2,000 years old and being born an Arab, but okay.

The is one of the most popular posts on Isiopolis. I’m reposting it today as I’m totally booked—with all kinds of good things. Goddesses, magic, and wonderful people! Hope you’ll enjoy it a second time around.