To Isis, a Veil

En Iset, Behen

This is a gift I bring before Isis the Hidden One, Who, Revealing Herself, Shakes Destiny: an invocation offering of a veil.

For You, Isis, a hiding, a hint, a whisper, an obscuration, a veil.

From behind it, may You send revelations into my sleep. Dreaming, I understand the inner voice and vision; I coax truth from my heart. Yet upon waking, the veil is torn asunder and I only half remember that which was so potent while I lay beneath Your veil.

O, but I adore Your mystery, Your obscurity, the crooked finger of Your concealing veil! Yes, Goddess, yes—veil Yourself in the depths of the indigo sky, in a blue-green blade of grass, in fire, in eyeshine in the darkness. For I could not bear the full brunt of Your beauty!

Draw me on with insinuations. Call to me with half-answered questions. Lead me with unknowns. And I shall ever follow, carrying the train of Your not-quite-translucent veil, hoping for another brief glimpse of You, beneath it.

Listen, O Isis, to the words of the Veil: “I am offered unto Isis as a kindness to mortals for I am their shield against the awe of the Goddess. Woven of darkness and daylight, the Cosmos itself is the loom upon which I was made. All things are connected to me in warp and woof. Tayet Herself, the Weaver, has made me, a perfect thing. I am the Uniting Mystery Never Quite Revealed. I am the Veil of Isis.”

Unto You, Isis, I offer this veil and all things beautiful and pure. M’den, Iset. Accept it, Isis.

The Veil of the Goddess

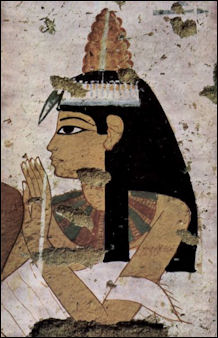

The phrase “the Veil of Isis” is so common that we might not question where it came from. But perhaps we should. For one thing, ancient Egyptian women generally weren’t veiled so it would be odd to see a Goddess depicted so. Oh, there were headdresses aplenty, but not concealing veils.*

By Ptolemaic times, under Greek influence, we do see veils as head coverings come into use, though they seem more decorative than anything else. Both Greek and Roman images of Isis often include a veil covering the back of the head and hair.

The phrase, Veil of Isis, comes to us from our Greek friend, Plutarch in his essay On Isis and Osiris. In it, he is talking about Egyptian Mysteries. He tells his readers that when the new pharaoh was crowned, he became privy to hidden Egyptian philosophy and notes that the Egyptians’ knowledge of their Deities “holds a mysterious wisdom.” To illustrate his point, he notes a certain seated statue of the Goddess of the Egyptian city of Sais. He says She is Athena “whom they [the Egyptians] consider to be Isis also.” She would, of course, be Neith, the Lady of Sais, Who was indeed assimilated to both Athena and Isis.

The statue bore an inscription: “I am all that was, and is, and shall be, and no mortal hath ever Me unveiled.” It speaks to the all-encompassing power and mystery of the Goddess.

If there was such an image, we have not yet found it. Since Plutarch was writing in the 2nd century CE and the Ptolemies came in long before that, about 300 BCE, it is possible that the image of Neith-Athena-Isis could have been veiled—at least with the decorative-type veil we see in images of some Ptolemaic queens.

Proclus, a Greek philosopher writing in the 5th century CE, also quotes the inscription and adds another line: “The fruit that I have brought forth the Sun has generated.” He doesn’t mention Isis, but rather Neith-Athena and speaks in terms of the Goddess being involved in creation processes, both visible and invisible.

There are a few other ancient references to the veil of Isis. The Greco-Egyptian magical papyri refer to it on several occasions. In one, the magician invokes Isis and asks Her to remove Her veil in order to reveal the future and “shake destiny.” By revealing the Mysteries beneath Her veil, the magician hoped that the Goddess Who was worshiped as Lady of Fate and Fortune could not only predict, but could change or “shake” destiny.

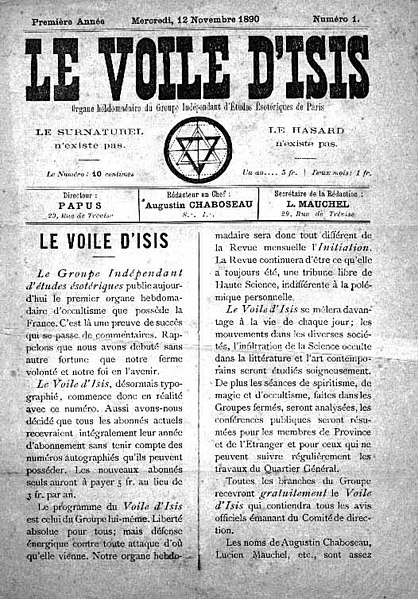

Even after the end of the open worship of the Pagan Deities in the Mediterranean, Plutarch and other Greek philosophers continued to be studied. Because of Plutarch’s mention of the inscription in relation to Isis, the idea of the veil of Isis formulated more and more strongly and eventually passed into the annals of the Western Esoteric Tradition. The unveiling of the Goddess became a symbol of the revelation of esoteric secrets, sometimes specifically the revelation of Egyptian secrets.

European esotericists of many kinds came to use the metaphor of the Veil of Isis for the hiding or revealing of their own secrets. By this time, Isis was identified with the Goddess Nature, Who hides Her secrets from those who seek to understand Her.

This idea was particularly important to the alchemists who sought to uncover Nature’s secrets—She Who is Isis and Venus and Ephesian Artemis and the Anima Mundi (World Soul). Freemasons took up the idea of a veiled Isis keeping their own secrets and some even found Egyptian antecedents in their rituals.

The Romantic movement, which rejected what they considered the coldness of the Enlightenment, preferring emotion and imagination, was also developing at this time. For Romantics, Isis’ veil concealed not just the scientific secrets of Nature, but a deeper, unexplainable Mystery that is, at the same time, Ultimate Truth.

Philosophers took up the metaphor as well. Immanuel Kant said of the Saite inscription: “Perhaps no one has said anything more sublime, or expressed a thought more sublimely, than in that inscription on the temple of Isis (Mother Nature).” Influenced by Kant, the physician, playwright, poet, and philosopher Friedrich Schiller (what a guy!) tells a tale in which a young initiate rashly removes the Veil from a sacred image of Isis and is found nearly dead the next morning by the wiser priests; apparently, the secret was just too much for him.

Following in those mysterious footsteps, Helena Blavatsky’s 1877 book, Isis Unveiled, is a compendium of occult lore that purports to draw aside the veil of the Goddess for its readers. It continues to influence occultists to this day.

As a metaphor, the Veil of Isis was ubiquitous for centuries. Alchemists, magicians, freemasons, philosophers, scientists, poets, novelists, and visual artists all desired to life Isis’ Veil to discover the deepest secrets and truths, truths about Nature and truths about human beings in Nature.

This post barely scratches the surface of the many ways and places people were inspired by the veil of the Goddess. I’ve expressed some of my thoughts in the Offering at the beginning of this post. What is the Veil of Isis for you?

* It is possible to see the daily opening and closing of the shrines that held the sacred images of the Egyptian Deities as a kind of unveiling and veiling of the images.