Dear rebels and resisters, I want you to know that Our Lady is right there with us.

It seems to be part of Her nature.

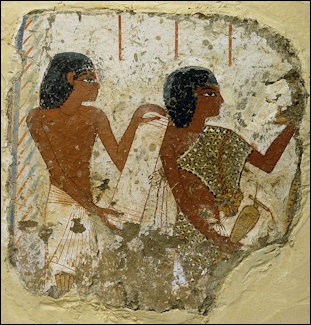

Interestingly, quite a number of ancient Athenian Isiacs—living under Roman imperialism—chose to have themselves represented on their tomb steles in Isiac dress as a way to reclaim some of their own individuality.

An article I was reading about this suggested that these people wanted to represent themselves in other than the standard Greco-Roman manner because it let them preserve some of their self definition and personal power (as well as cultic status) in an era when they felt they had little of it politically. And, of course, these people were mostly, but not all, women—people who have had little political power at the best of times, in ancient society and now in far too many places.

In other words, these people were rebelling against Roman societal rule in a way that helped them fashion new and more complex selves—and Isis helped them do it.

Oh, but it started much earlier than that.

Although you still see Isis described as “the ideal wife and mother”—which often has connotations of 1950s housewife—I’ve always thought of Her as quite rebellious in that She always does exactly what She wants to do, and does not let anything stop Her.

That’s why I was taken aback when a friend once remarked to me that she couldn’t get into Isis because of the subservient way She went around “picking up after Osiris.” My friend was, of course, referring to the main Isis-Osiris myth in which Isis travels the length and breadth of Egypt to find and conduct proper funeral rites over the scattered pieces of Her murdered husband’s body.

I, on the other hand, have always considered the ancient myth of Isis to be pretty darned feminist, modeling both feminine power and independence. Indeed, my own feminism is one of the reasons I began exploring Goddess in the first place.

My friend had seen the Isis-Osiris myth as just another “woman-taking-care-of-her-man” story, while I’d seen it as precisely the opposite: a tale of the reversal of stereotypes. Instead of the prince saving the princess, the princess had to save the prince, put him back together, and give him renewed life.

We were both right, of course. A myth speaks to us however it speaks to us. Nevertheless, I think that Isis and Her cycle of myths, especially when you include the important Isis & Re story, provide a proto-feminist model.

Part of the credit for this goes to ancient Egyptian society. While we should have no illusions that men and women were true equals in Egypt, still they were more equal in Egypt than in any of Egypt’s Mediterranean neighbors. In Egypt, women could hold and sell property; they were considered (at least theoretically) equal to men before the law; they could instigate lawsuits; they could lend money; and although it was unusual, a woman could live independently, without a male guardian. In contrast, Greek and Roman laws firmly relegated women to control by their husbands or male relatives and provided little economic or legal protection to women.

So when Isis’ myths depict Her acting autonomously for Her own ends or wielding power, this type of female behavior was not as strange in Egypt as it was in the rest of the Mediterranean world. Another example of Isis wielding power are the tales of Isis as warrior that we have from the tales in the Jumilac papyrus.

Even when Egypt was ruled by non-natives under the Ptolemies (from 305 to 30 BCE), the native Egyptian respect for the feminine and The Feminine seems to have crept in. By the end of the dynasty, the historian Diodorus Siculus (Diodorus of Sicily) could write that due to the success of Isis’ benevolent rule of Egypt (while Osiris was on His mission to civilize the world):

…it was ordained that the queen should have greater power and honor than the king and that among private persons the wife should enjoy authority over her husband, the husbands agreeing in the marriage contract that they will be obedient in all things to their wives.

Diodorus Siculus, Book II, section 22

This wasn’t true, but it is interesting that it would be the impression that Diodorus received when visiting Egypt and speaking to Egyptians.

I’m also reading an article in the Journal of Hellenic Studies by Rachel Evelyn White about women in Ptolemaic Egypt that discusses the possibility that the family tomb may have been the property of a female heir, and which was likely a holdover from ancient Egyptian tradition. This is based on some Egyptian contracts of the time combined with the fact that this was specifically the case among the nearby Nabataeans. If so, this could be one of the bases for retained female power in Egypt, as well as giving women another connection with Isis as the provider of proper burial and funerary rites. It may also point to very ancient matrilineal (not matriarchal) traditions in Egypt.

We should also recall that in several of the remaining Isis aretalogies, the Goddess declares women’s equality with men. What’s more, the relationship between women and men is meant to be friendly and loving—like the relationship modeled by Isis and Osiris. The aretalogy from Maroneia states that Isis established language so that men and women, as well as all humankind, should live in mutual friendship.

In a later Hermetic text entitled Kore Kosmu, Isis explains to Horus the origin and equality of male and female souls, declaring that:

The souls, my son Horus, are all of one nature, inasmuch as they all come from one place, that place where the Maker fashioned them; and they are neither male nor female; for the difference of sex arises in bodies, and not in incorporeal beings.

Scott, Walter, Hermetica, Vol. 1 (Boulder, Colorado, Hermes House, 1982), p. 499-501.

The Oxyrhynchus Invocation of Isis states it quite plainly: “Thou [Isis] didst make the power of women equal to that of men.” I know of no other ancient texts that lay out the message of equality so strongly as is done in the Isis aretalogies and hymns.

And so, I honor Our Lady, Isis the feminist, Isis the rebel and resister. May She help and support us in this difficult time.