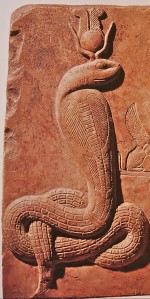

We are not immune to the charms of a beautiful head of hair—and the ancient Egyptians weren’t either.

But they took appreciation for hair, especially feminine hair, to a whole new level of magnitude. For them, hair was magical. And, of course, Who would have the most magical hair of all? The Goddess of Magic: Isis Herself.

I have always understood that the long hair of Isis in Egyptian tradition—disarrayed and covering Her face in mourning or falling in heavy, dark locks over Her shoulders—to be the predecessor of the famous Veil of Isis of later tradition. Ah, but there is so much more.

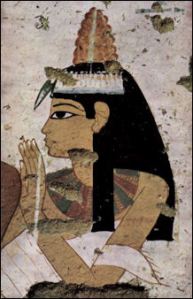

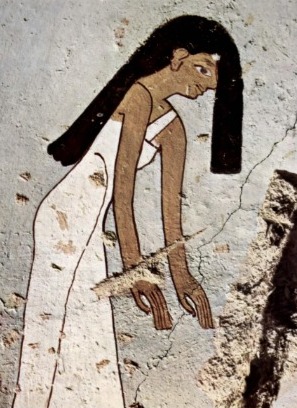

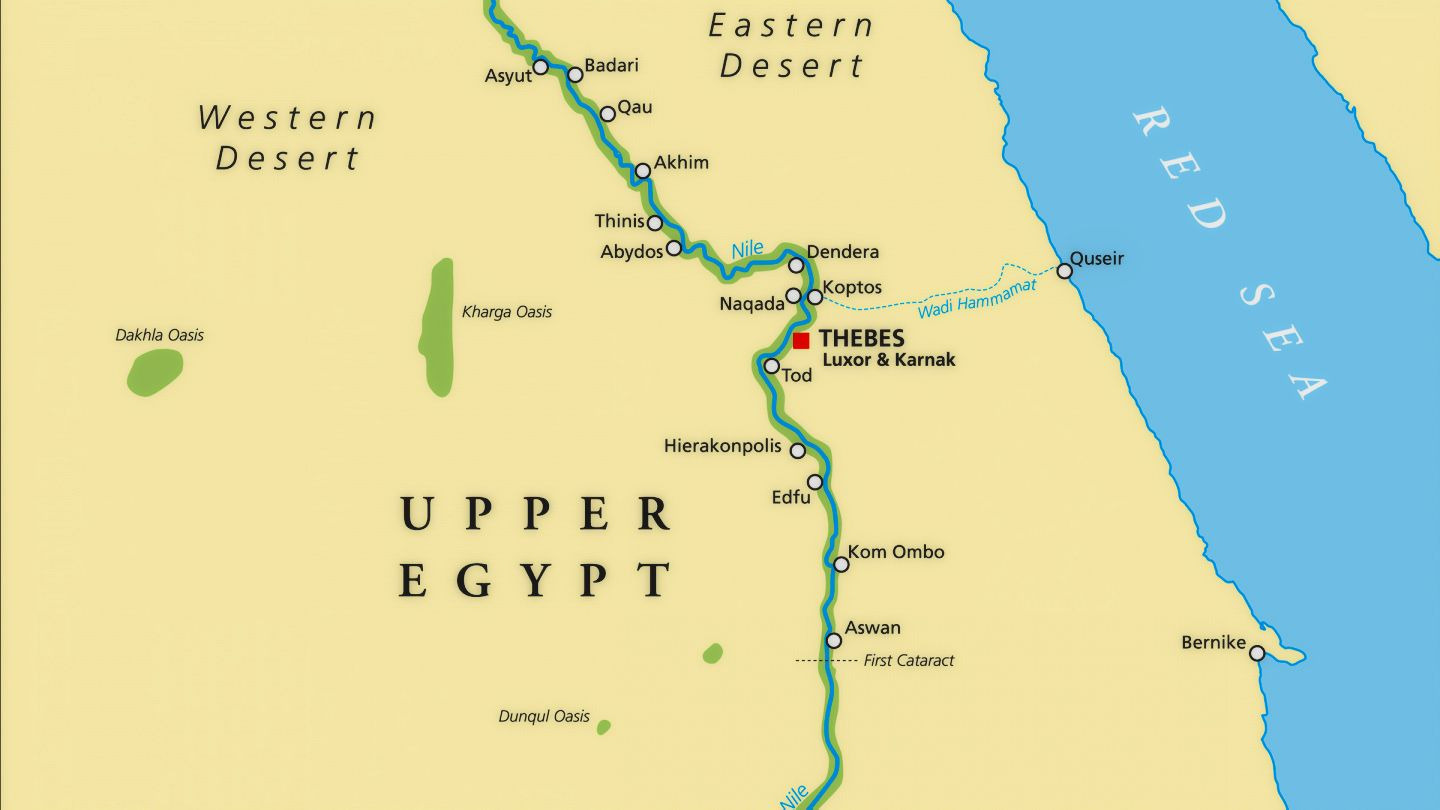

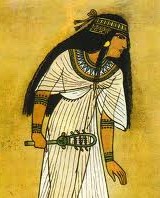

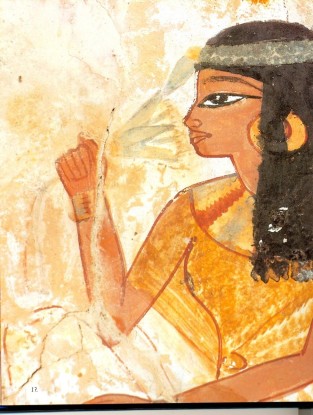

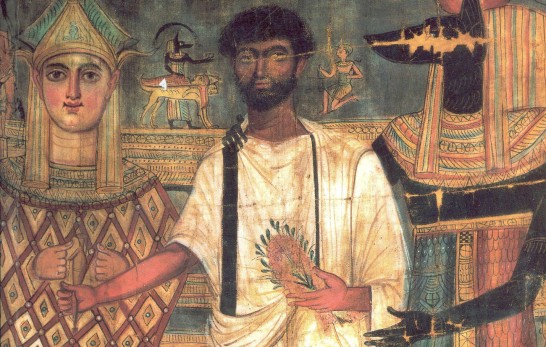

In ancient Egypt, it was a mourning custom for Egyptian women to dishevel their hair. They wore it long and unkempt, letting it fall across their tear-stained faces, blinding them in sympathy with the blindness first experienced by the dead. As the Ultimate Divine Mourner, this was particularly true of Isis. At Koptos, where Isis was notably worshipped as a Mourning Goddess, a healing prayer made “near the hair at Koptos” is recorded. Scholars consider this a reference to Mourning Isis with Her disheveled and powerfully magical hair.

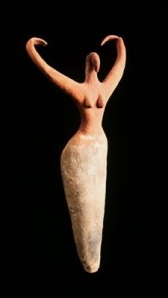

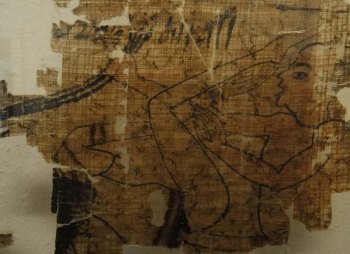

It is in Her disheveled, mourning state, that Isis finally finds Osiris. She reassembles Him, fans life into Him, and makes love with Him. As She mounts His prone form, Her long hair falls over Their faces, concealing Them like a veil and providing at least some perceived privacy for Their final lovemaking. As the Goddess and God make love, the meaning of Isis’ hair turns from death to life. It becomes sexy—remember those big-haired “paddle doll” fertility symbols?

This pairing of love and death is both natural and eternal. How many stories have you heard—or perhaps you have a personal one—about couples making love after a funeral? It’s so common that it’s cliché. But it makes perfect sense: in the face of death, we human beings must affirm life. We do so through the mutual pleasure of sex and, for some couples, the possibility of engendering new life that sex provides. The lovemaking of Isis and Osiris is the ultimate expression of this. Chapter 17 of the Book of Coming Forth by Day (aka the Book of the Dead), describes the disheveled hair of Isis when She comes to Osiris:

“I am Isis, you found me when I had my hair disordered over my face, and my crown was disheveled. I have conceived as Isis, I have procreated as Nephthys.” (Chapter 17; translation by Rosa Valdesogo Martín, who has extensively studied the connection of hair to funerary customs in ancient Egypt.)

There is also a variant of this chapter that has Isis apparently straightening up Her “bed head” following lovemaking:

“Isis dispels my bothers (?) [The Allen translation has “Isis does away with my guard; Nephthys puts an end to my troubles.]. My crown is disheveled; Isis has been over her secret, she has stood up and has cleaned her hair.” (Chapter 17 variant, translation by Martín, above.)

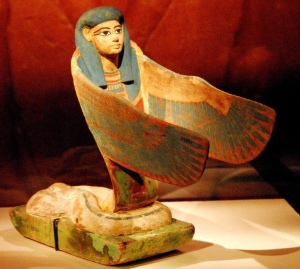

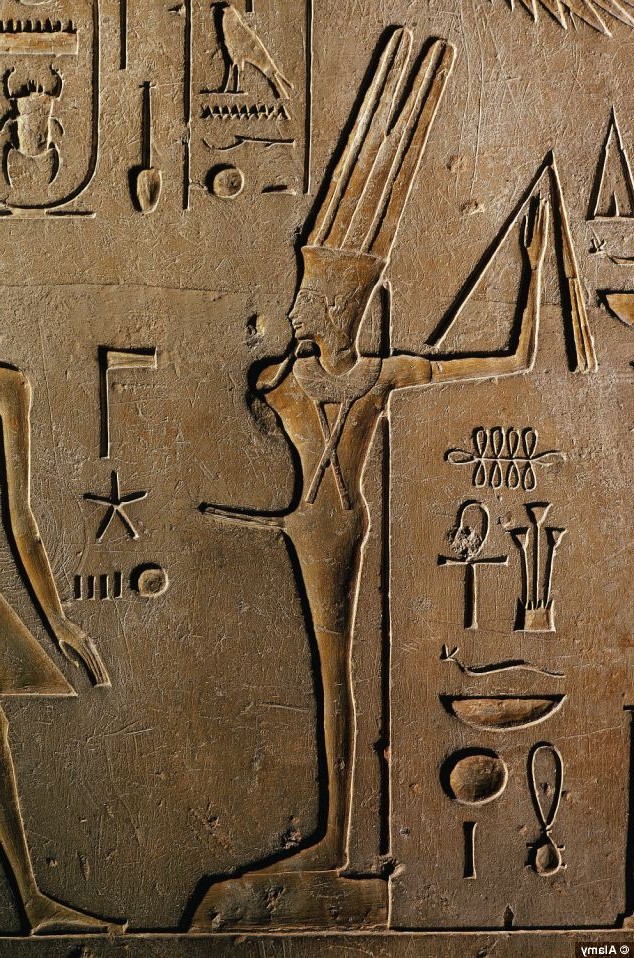

This lovemaking of Goddess and God has cosmic implications for its result is a powerful and important new life: Horus. As the new pharaoh, Horus restores order to both kingdom and cosmos following the chaos brought on by the death of the old pharaoh, Osiris.

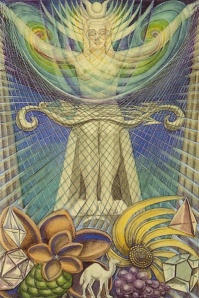

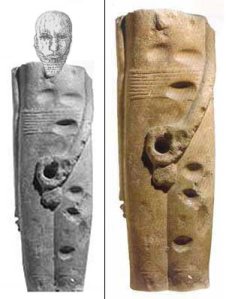

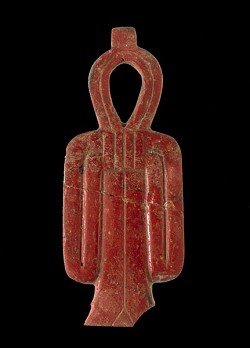

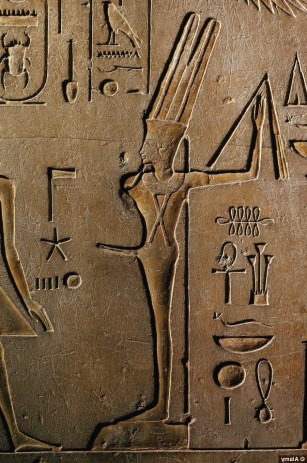

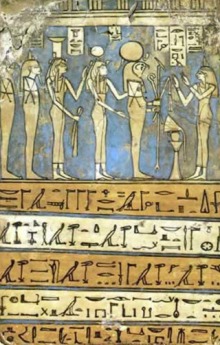

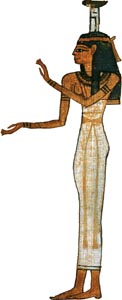

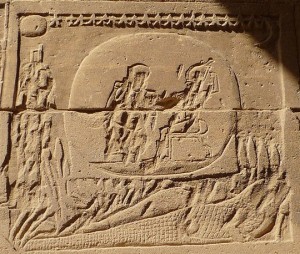

Not only is hair symbolic of the blindness of death and the new life of lovemaking; the hair of the Goddesses is actually part of the magic of rebirth. Isis and Her sister, Nephthys, are specifically called the Two Long Haired Ones. The long hair of the Goddesses is associated with the knotting, tying, wrapping, weaving, knitting, and general assembling necessary to bring about the great Mystery of rebirth. Hair-like threads of magic are woven about the deceased who has returned to the womb of the Great Mother. The Coffin Texts give the name of part of the sacred boat of the deceased (itself a symbolic womb) as the Braided Tress of Isis.

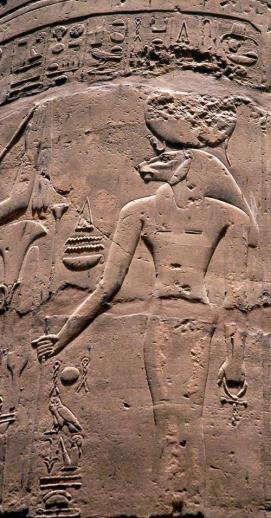

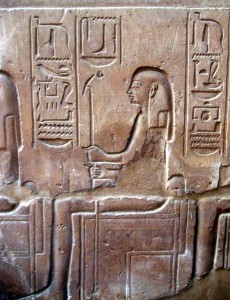

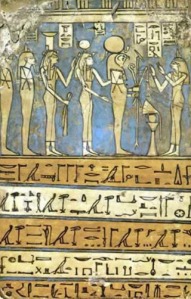

In some Egyptian iconography, we see mourning women, as well as the Goddesses Isis and Nephthys, with hair thrown forward in what is known as the nwn gesture. Sometimes they/They actually pull a lock of hair forward, especially toward the deceased, which is called the nwn m gesture. It may be that this gesture, especially when done by Goddesses, is meant to transfer new life to the deceased, just as Isis’ bed-head hair brought new life to Osiris. It is interesting to note that the Egyptians called vegetation “the hair of the earth” and that bare land was called “bald” land, which simply reiterates the idea of hair is an expression of life.

Spell 562 of the Coffin Texts notes the ability of the hair of Isis and Nephthys to unite things, saying that the hair of the Goddesses is knotted together and that the deceased wishes to “be joined to the Two Sisters and be merged in the Two Sisters, for they will never die.”

The Pyramid Texts instruct the resurrected dead to loosen their bonds, “for they are not bonds, they are the tresses of Nephthys.” Thus the magical hair of the Goddesses is only an illusory bond. Their hair is not a bond of restraint but rather the bonding agent needed for rebirth. Like the placenta that contains and feeds the child but is no longer necessary when the child is born, the reborn one throws off the tresses of the Goddesses that had previously wrapped her or him in safety.

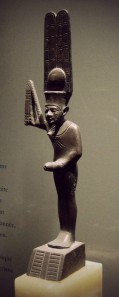

The Egyptian idea of Isis as the Long-Haired One carried over into Her later Roman cult, too. In Apuleius’ account of the Mysteries of Isis, he describes the Goddess as having long and beautiful hair. Her statues often show Her with long hair, and Her priestesses were known to wear their hair long in honor of their Goddess.

This little bit of research has inspired me to want experiment with the magic of hair in ritual. In Isis Magic, the binding and unbinding of the hair is part of the “Lamentations of Isis” rite (where it is very powerful, I can tell you from experience), but I want to try using it in some solitary ritual, too. I have longish hair, so that will work, but if you don’t and are, like me, inspired to experiment, try using a veil. It is most certainly in Her tradition. (See “Veil” in my Offering to Isis.)

If you want to learn more about the traditions around hair and death, please visit Rosa Valdesogo Martín’s amazing and extensive site here. That’s where most of these images come from…many of which I had not seen before. Thank you, Rosa!

I have her book on the subject on order, but the publisher has postponed its release several times. Here’s hoping it arrives sometime soonish.

As the days grow longer, a certain soft joy fills me.

As the days grow longer, a certain soft joy fills me.