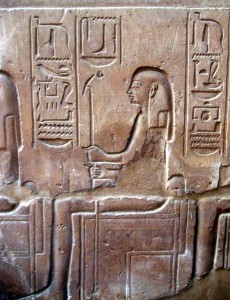

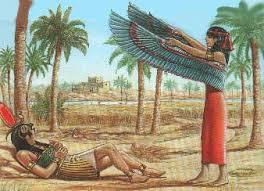

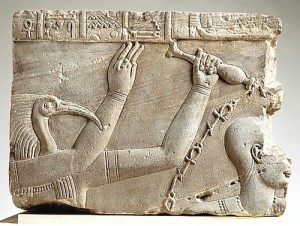

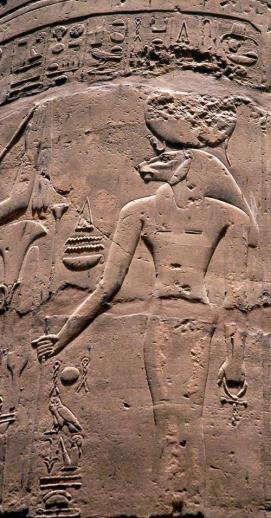

More from the Temple of Isis at Dendera.

In this one small, mostly destroyed temple, there are many Deities speaking.

They are everywhere, on every wall. Many are well known, like Tefnut and Hathor and Thoth; some more obscure. The king—always said to be beloved of Isis and Ptah—is ubiquitous as well as he makes many different offerings of many different kinds. And, as this is the temple of the birth of Isis, She Who is First Born Among the Goddesses, there is much rejoicing in this small temple.

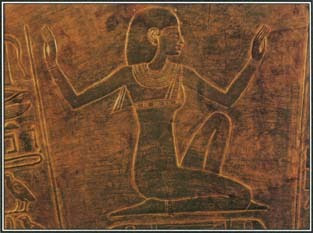

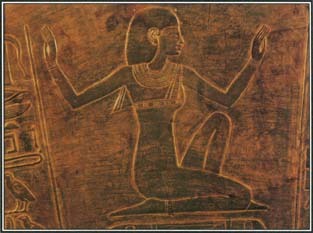

For example, the Goddess Merit, the Enchantress Who is here called “Lady of the Throat,” uses Her beautiful throat and voice to arouse joy and bring intoxication; She also leads the dances for Isis. Isis Herself is Mistress of Intoxication Who Arouses joy, Whose Heart is Satisfied with Revelry. Nuet declares that She “makes every person rejoice to see You [Isis].” Hor-Ihy, a combination of Isis’ son Horus with Hathor’s son Ihy, plays the sistrum “for the Mistress of the Sistrum-Temple, Isis the Great, Mother of the God.” The Gods dance for Her. The Goddesses are joyful for Her. The women play the tambourine for Isis the Luminous One. Hathor, Mistress of the Sweet Breath, sings for Her.

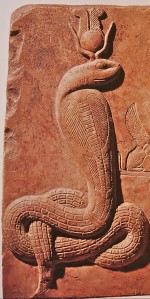

A lot of what we find in this temple, as we did in Hathor’s, are the various names of the Goddess Isis in other parts of Egypt. Interestingly, an inscription on this temple is also one source for our understanding of the Goddess Bast (or Bastet) as “the soul of Isis.” It comes from one of those inscriptions where Isis is being described as a Goddess of various names in other Egyptian locales. And one of those names is

“Nbt B3st (Lady Bast or the Lady of Bubastis) is the Heliopolitan. B3 n 3st [ba or “soul” of Isis] it is said of Her name. B3t is Her name in the mouths of human beings from ancient times of the Deities until now.”

We can be pretty sure that the Egyptians were engaging in some word play here—word play that is intended to reveal mysteries. If you look at the transliteration (writing the hieroglyphs in “latin” or “roman” letters; with the addition of some special characters) of Bast’s name and Isis’ name, you will see that the letters for Isis are within the name of Bast: B3st and 3st. The “3” here does not really represent a three, but is one of those special characters; it is sometimes called aleph, from Hebrew, because it is a consonant that is also “sort of” a vowel, as aleph is in Hebrew. For simplicity’s sake, we are usually told to pronounce it like an English long “a,” (ah). But it isn’t really an a. It’s a glottal stop. Here’s how that works in Isis’ Egyptian name.

So, what the Egyptians were telling us is that Bast and Isis are linked because from within the name Bast, Isis is revealed. This is expressed by writing that B3 n 3st [Ba/soul of Isis] it is said of Her name.” But “ba” in Egypt isn’t really what we usually mean by “soul” though that is a conventional translation. The concept of the ba is much, much more complicated—and I’ll post on that sometime, but not today.

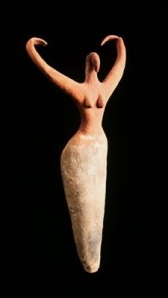

But in short, ba is one way that a Deity can express Themselves. Ba is an active manifestation of a Deity. So a better way to think about it would be that Bast can be a manifestation of Isis. Or that Isis can express Herself as Bast. This is very much in line with the very fluid way Egyptian Deities can flow into or become each other or express Themselves as each other.

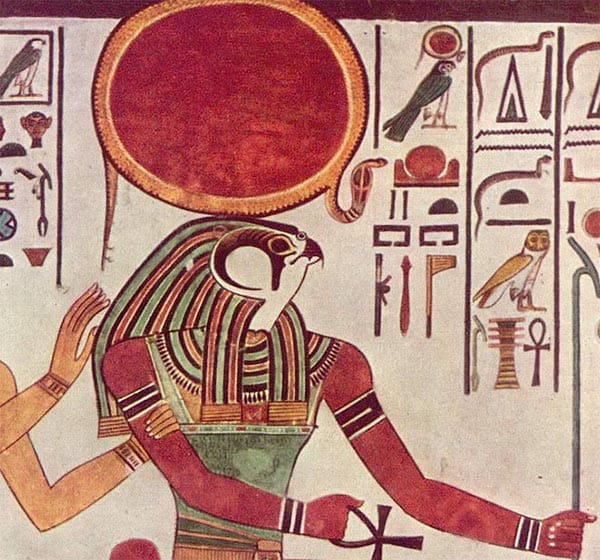

In the final line of this section of the inscription, it says B3t, or Baet, is Her—in this case, Isis’—name “from ancient times of the Deities until now.” This is not a reference to the Cow Goddess Bat or Ba-et. Instead, it is an expression of Isis’ immense power. The ba-power of a Deity made manifest is often written in the plural, bau, though often treated as a singular. The plurality not only intensifies the power, but also recognizes that the Deity is not limited to a single manifestation of power. For example, wind is the bau of Shu. The stars are the bau of Nuet. And both have other bau as well.

Thus to be the Goddess Baet, Whose very Name—from ancient times until now—IS this ba-power, is to be powerful indeed. We learn about Isis’ bau in other inscriptions at Dendera as well. She is said to be the One “Whose bau is great.” In fact, “Her bau is greater than all the Gods.” As a Baet Goddess, She shares this great might with only few other Goddesses, such as Hathor, Neith, and Nephthys. As a Baet Goddess, She shows Her power on earth, where humankind bows to it, and in the heavens, where She is B3t em pt, the Mighty One in the Sky.

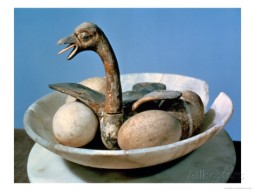

On another wall of Her temple, at least a dozen Deities “open the New Year” for the Daughter of Nuet, Isis the Goddess. We even have the founding date for the current temple: July 16, 54 BCE. That was the day of the heliacal rising of the Star of Isis, Sirius, and—the temple records—that for a brief time that morning, both moon and sun were seen in the sky. So both Re and Osiris were there to greet Isis at the foundation of Her Horizon or Akhet Temple. It is so called, no doubt, due to its orientation to the east and the rising of Her Star, as well as the regenerative power of the liminal space of the Akhet.

We also learn that,

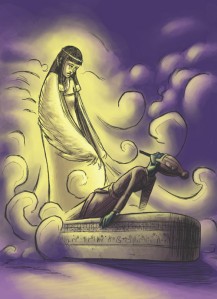

“On this beautiful day, the Day of the Child in His Nest, [there is] a great festival throughout the country, Isis is given birth at Dendera by Thoueris [meaning the Great One, in this case, Her mother Nuet] in the temple of the Venerable [Isis].”

And that Isis was born as

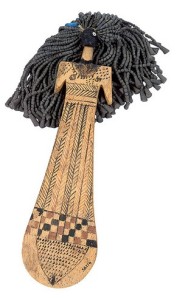

“a woman with black (kemet) hair and red (desheret) skin, full of life, Whose love is sweet.”

This must also be word play, for Isis is born with the colors of the Black Land and Red Land shown forth in Her Divine form and so She rules over both; She rules over all things.

Indeed, even from before Her birth, Isis was destined to rule.

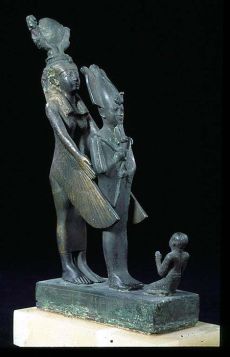

“Destiny distinguishes Her on the birthstones. Her heart is rich in all virtue. The south is given to Her until [that is, “as far as”] the [place of the] rising of the Disk, the north until the limits of Darkness. She is mistress of the sanctuaries of Egypt with Her son and Her brother Osiris.”

Isis is Queen of Upper and Lower Egypt and She rules the Two Lands “from the bricks of birth.” She is the ruler of cities and sanctuaries; indeed She is the Venerable One Without Equal, the Regent Who Governs the Universe.

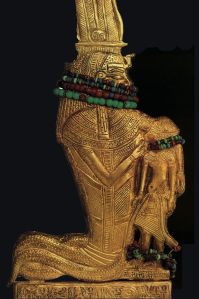

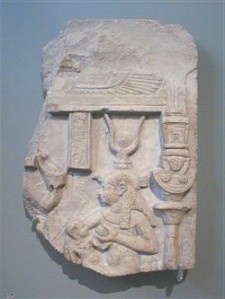

Just as Isis’ own birth is celebrated in this temple, so Her birth-giving to Horus is also celebrated. Isis is called “the Primordial, the First to Give Birth Among the Goddesses, the One with the Beautiful Face, Whose Milk is Sweet.”

I’ve just scratched the surface here. There’s definitely more. Next time, we’ll look into some of the birth-associated texts and images to see what we can learn there.