How many of us were Egyptophiles from very early on in our lives, even as children? That’s true of me. You, too?

The power of ancient Egypt is magnetic, irresistible. And our Goddess Isis is perhaps THE most well known—and for some of us, most magnetic and irresistible—of the representatives of Her ancient homeland.

We are not alone in our attraction to Egypt and to Isis. We’re not alone today, and we’re not alone historically. Fascination with Egypt and devotion to Isis spread far beyond the borders of ancient Egypt. In the beginning, Isis was a local Deity. Eventually, Her worship and that of Osiris spread throughout much of Egypt. By the 5th century BCE, the Greek historian Herodotus said Theirs was the only pan-Egyptian worship. (This isn’t so, but it shows how widely their worship had spread within Egypt.)

Even during archaic times (as early as 800 BCE), we see traces of devotion, such as inscriptions or votive images, outside of Egypt. By the 4th century BCE, Isis and Her family were adopted into Nubia to the south of Egypt and Greece to the north. Then, from the beginning of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt (305-30 BCE) through the Roman Empire, devotion to Isis spread very quickly.

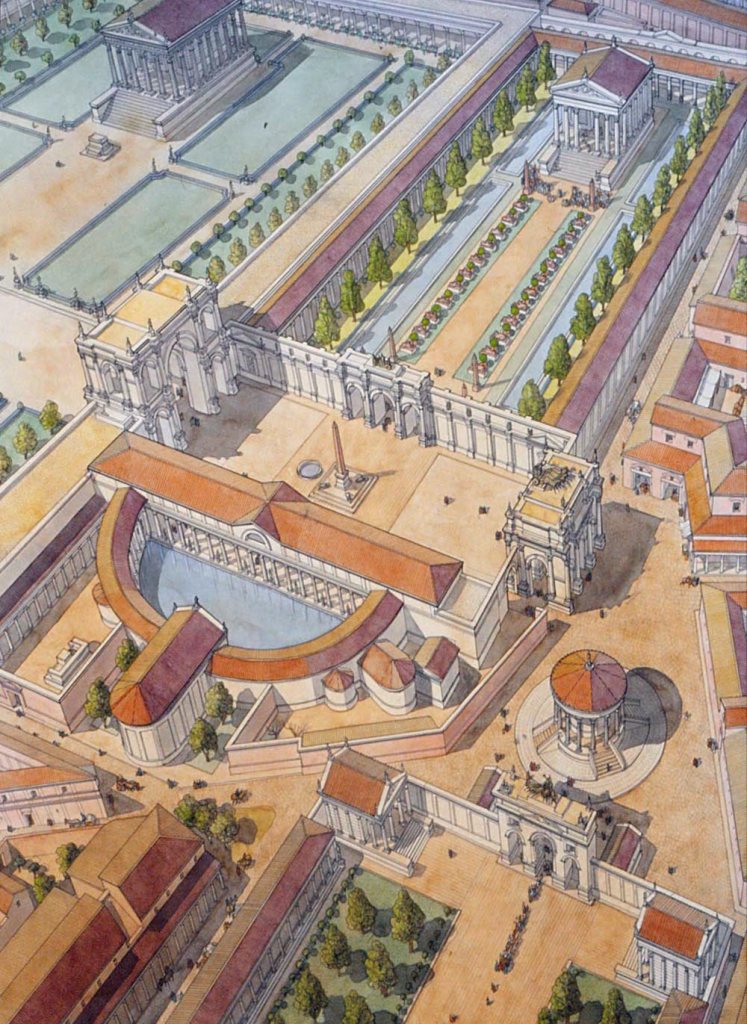

Due to some ancient documents we still have, we can know that the first temple of Isis was built in Greece, in the Piraeus, Athens’ port city, by the late 4th century BCE. I found an article detailing how that may have come about.

The first thing we hear of it is in a legal document that the folks who had received said document had carved in stone and set up in the Piraeus. They wanted to make sure there would be no mistake that they had proper permission. The people who had it carved were from Cyprus and they had gained permission to set up an Aphrodite sanctuary. The interesting thing for Isiacs is that they had done it on the precedent of Egyptians having built a sanctuary of Isis in the same area. The document is dated to 333/2 BCE. So this means that the formal worship of Isis was established in the Athens area sometime before 333/2 BCE. On the Greek holy island of Delos, sometime about this same period, an altar dedicated to Isis is the oldest of the inscriptions related to the Egyptian Deities.

The person who had proposed that Athens grant this permission to the Cyrians was a guy named Lycurgus who was in charge of Athenian finances, and so was quite powerful. At least one scholar has suggested that he had something of a personal interest in the previous Isian sanctuary. His grandfather, also named Lycurgus, may have been the one who proposed that the Egyptians be allowed to build their sanctuary. If it was Lycurgus senior who was connected with the Egyptians and their sanctuary, then that would put the establishment of an Isis temple at Athens about the late 5th century BCE.

However, getting foreign sanctuaries built was not an easy thing. And in fact, Lycurgus senior was thoroughly mocked for his promotion of the Egyptian Deities. He was nicknamed “Ibis” in Aristophanes’ comedy, The Birds. An ancient scribe commenting on this nickname opined that he was called that either because he was Egyptian by birth or due to “his Egyptian ways.” A fragment from another comedian pictured Lycurgus wearing a kalasiris, the long, form-fitting sheath dress of an Egyptian woman. Yet another suggests that Lycurgus might be carrying messages home to “his fellow countrymen” in Egypt.

Most scholars are pretty sure Lycurgus senior wasn’t Egyptian—and are certain that he was an Athenian citizen—but it seems that he may have indeed been an Egyptophile. What we don’t know for certain is whether Lycurgus the younger was actually the grandson of Lycurgus the Ibis. So there may be no connection at all and the names merely coincidental. The author of the article I’m reading suggests that grants to both to the Isis and Aphrodite devotees may have been more political than religious. Athens had suffered some defeats during this time period. The author suggests that Lycurgus the younger was welcoming sanctuaries from other areas so that he could help build up Athens’ trade and thus its economic power. So it’s always money.

While it may have been money for Lycurgus the financial administrator, it wasn’t just money for other Isis-interested people in the Mediterranean. For instance, we see more Greek parents giving their children names that included Hers at about these same times. Scholars generally agree that when we see an upswing in what are known as theophoric names (“Deity-Bearing” names; for instance, “Isidora” is a theophoric name), we are witnessing an increase in the Deity’s popularity as well. In Greece, we see a few Isis-bearing names in the 3rd century BCE, many in the 2nd century BCE, then an absolute explosion of Isis names from the 1st century BCE through the Roman Imperial period.

Perhaps even more interesting is that people may have taken names that included Hers as a sign of their devotion. This is not so different today. My own theophoric name is a taken name that I legally changed to permanently connect me with Her. And I know I’m not the only one.

Isis may have been especially important in Miletus, an ancient Greek city in what is now Turkey. There are five women, known from their funerary reliefs, who all bore the name Isias (or Eisias) and had come to Athens from Miletus. Some scholars have suggested that these women may have been former slaves who were freed in the name of Isis and therefore took the name of their deliverer. Others have suggested that they were initiates of Isis who took Her name—or that they may have been both.

The five Isis-named women were shown on their grave reliefs in the famous “dress of Isis,” that is, the fringed mantle with Isis knot, and holding the sistrum and situla. But theirs were not the only examples. In fact, we know of 108 such Attic reliefs of women and some men with Isis attributes; the women wear the Isis-knotted dress, while the men hold the sistrum and situla. During the Roman period in Athens, this number makes up one-third of all the known (and published) grave reliefs. If that number reflects true percentages rather than just chance, that’s an awful lot of Isiacs.

In addition to the possibility that these Isis-accoutered people were initiates of Isis, it has also been suggested that they may have either been priest/esses, had a priest/essly function, or may simply have been especially enthusiastic devotees; for example, volunteers who helped maintain the sanctuaries and participated in the rites.

Or they may have been members of religious associations that were connected with the sanctuaries and served both a religious and social function. We know of one such group in particular that was connected to one of the Isis-Sarapis sanctuaries on Delos. It seems likely that enthusiasts would be members, or even founders, of such associations.

People could also stay for a time at the temples. In Apuleius’ tale of initiation into Isis’ Mysteries, prior to deciding to be initiated, his character Lucius simply spends time in Isis’ sanctuary:

I took a room in the temple precincts, and set up house there, and though serving the Goddess as layman only, as yet, I was a constant companion of the priests and a loyal devotee of the Great Deity.

Apuleius, the Golden Ass, Book XI, 19

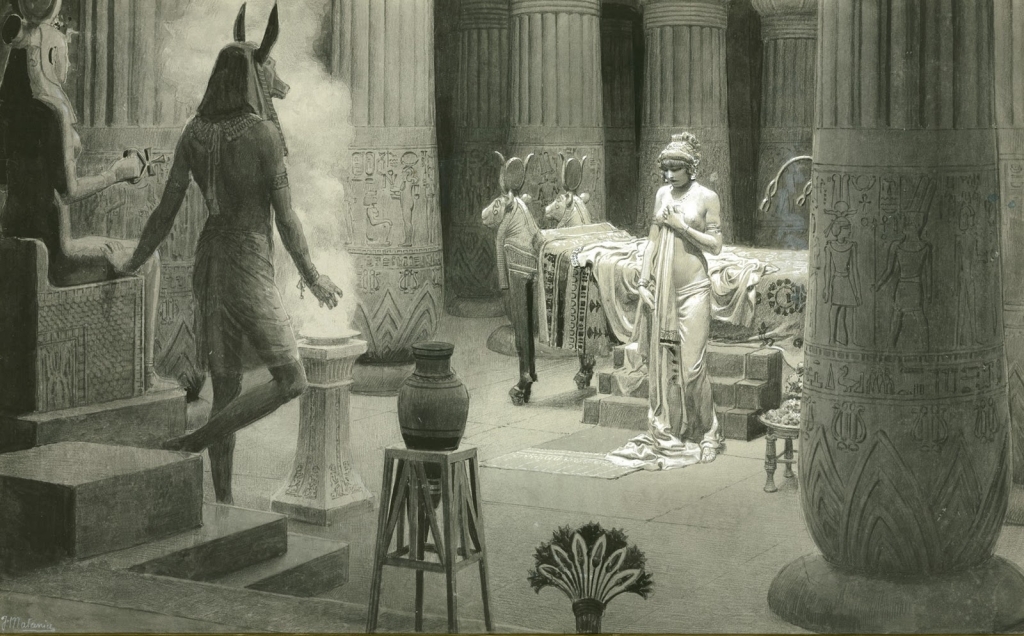

I wish he had described what specific things he, as a layperson, was allowed to do to serve the Goddess. He does describe, in part, the morning rites to which the public seems to have been welcomed:

I waited for the doors of the shrine to open. The bright white sanctuary curtains were drawn, and we prayed to the august face of the Goddess, as a priest made his ritual rounds of the temple altars, praying and sprinkling water in libation from a chalice filled from a spring within the walls. When the service was finally complete, at the first hour of the day, just as the worshipers with loud cries were greeting the dawn light…

Apuleius, the Golden Ass, Book XI, 20

From the evidence we have from Greek Isis sanctuaries, it seems that the Greeks used priest/essly titles they were familiar with, but with adaptations to fit Isis’ mythos. We have records of a hiereus, a priest, a stolistes, one who adorns the sacred image of Isis, a zakoros, an attendant, a kleidouchos, a key bearer, and a melanophoros, a bearer (or wearer) of the black garments—Isis’ black garments of mourning. We can expect that Isis received offerings of food and drink, as did native Greek Deities.

We have mentions from several Roman writers about devotions to Isis. The poets Propertius and Tibullus complain of the period of sexual abstinence their mistresses undertook for Isis. Ovid writes of the crowds of penitents at the temple of Isis. Tibullus also mentions a ritual called votivas reddere voces in which devotees could join in the singing of the virtues (aretai) of Isis in front of Her temple twice a day. (I wonder if they used any of the aretalogies of Isis we know of.)

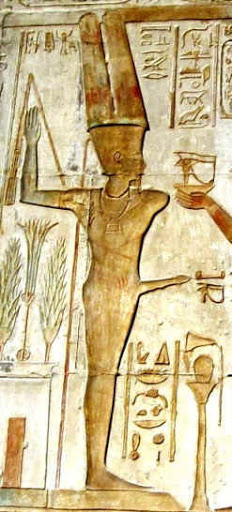

Interestingly, when Isis comes to Rome, Her Roman worshipers seemed to have tried to make Her worship more “Egyptian” than did Her Greek worshipers. For instance, Roman Isis temples celebrated the rising of Sothis. They added back Egyptian symbols, such as the divine animals: crocodile, baboon, and canine. We see the development of lifelong priesthoods, something done in Egypt, but not done in Greece. Some Roman emperors may have especially appreciated the Egyptian relationship between Isis the Throne and the pharaoh. And it is in Italy that we first see priestesses of Isis rather than just priests.

For modern devotees, knowing the ways in which our spiritual ancestors—whether in Her homeland of Egypt or outside of its borders— honored Isis can inspire us in developing our own ways to honor Her. Whether we make offerings of food upon Her altar, pour libations of milk and wine, or sing of Her virtues before our shrines, we honor the Goddess Who fills our hearts and we connect with those who have gone before us.