I have a new Isis accoutrement for you.

I love it when I find out new things—or new things about an old thing. This one is sort of an expansion on a previous thing.

Many of you may already be familiar with what are known as “black Isis bands,” which are needed in a number of rites in the Greco-Egyptian Magical Papyri (aka Papyri Graecae Magicae or PGM).

We can’t be sure, but I’ve theorized that these were made from the black cloth that had previously been used to clothe the sacred images of Isis, once the older robes had been replaced. Since the fabric was black, it would have been from Hellenized images of the Goddess. Egyptians did use cloth, both as offerings and to adorn their sacred images, but black cloth was not among the colors they generally favored.

What I’d like to share with you today is a different type of Isis band, an entirely Egyptian one. This band was given to Isis as an offering (see Offering to Isis, “Black Isis Bands”), and it was also worn by Her as part of one of Her various crowns. The information I’m working from is a dissertation by Barbara Ann Richter on The Theology of Hathor of Dendera. At Dendera, Isis is almost as prominent as Hathor. (And you’ll recall that Isis’ sanctuary at Philae also has a Temple of Hathor. Sisters!)

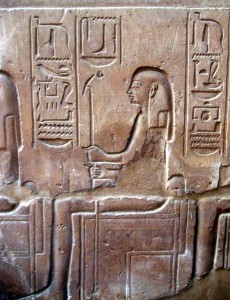

On the walls at Dendera, we see scenes with Isis wearing this particular crown, which consists of the Egyptian red and white Double Crown, one or two ostrich feathers, and the “seshed” band, which is wrapped around the base of the red crown—or sometimes around the headdress of Isis.

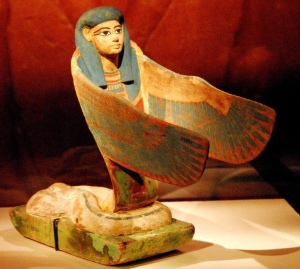

We even have a 3D image of what this crown with its seshed band may have been like. Near the sacred lake at the Dendera temple, archeologists found a cache of ritual items including a cult statue of Isis with the double crown and seshed band—except in this case, the seshed is around the Goddess’ wig rather than around the base of the crown. (Although, in this picture, it looks to me like there is something—possibly multiple serpents?—around the base of the crown.) There are also two holes in the white crown, which Richter suggests may have been meant to hold real (or separate) ostrich feathers.

The crowns and headdresses that the Egyptians represented the Deities wearing have specific meanings. The Double Crown represents rulership over the Two Lands, that is, Lower and Upper Egypt. The ostrich feather is the shut, the symbol of Ma’et—that which is Right, True, and Just. The seshed band is entwined by a uraeus serpent that is both protective and unifying, like the Double Crown.

In the Temple of Birth at Dendera (which I think is the Temple of the Birth of Isis), the king presents this crown to Isis and says, “Take for Yourself the seshed band. It has encircled Your forehead. The uraeus is united with Your head. The red crown and the white crown—they join together on Your forehead, the two feathers united beside them.” This crown emphasizes the unification of the land of Egypt as well as the powerful protection of the uraeus serpent. Since the crown is united with the Goddess, She embodies these qualities. And, of course, the Goddess bestows these same powers on the king in return, so we find the king wearing the seshed band at times, too.

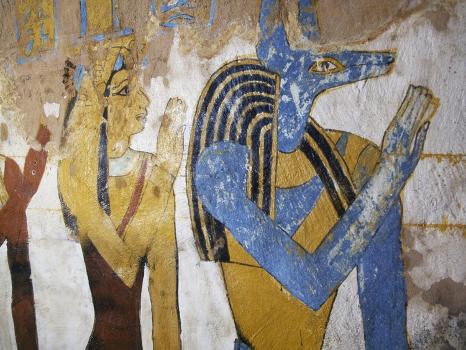

The feathers “united beside them” allude to Isis’ description as “Lady of Ma’et, the uraeus on Her forehead, appearing with Ma’et every day.” In this inscription, however, the word translated as “uraeus” isn’t “uraeus.” It’s Mehenet, which is the feminine version of the protective serpent Mehen, meaning “the Coiled One.” Mehen protects the God Re by encircling Him as He travels through the underworld; He also protects Osiris. Since Isis is a Goddess, She is united with the feminine serpent Mehenet. As a fiery Uraeus Goddess Herself, Isis protects Re and She is also the foremost protectress of Her husband Osiris as well as Her son Horus (and thus, the king). Mehen and Mehenet are sometimes shown with Their tails in Their mouths, making Them the prototype of the ‘serpent biting its own tail’ and later known as the oroboros.

In some of the Coffin Texts spells, Mehen is closely connected to Re. Coffin Text 760 tells us that after Isis brings Mehen, the Coiled One, to Her son Horus, Horus becomes “the double of the Lord of All,” that is, the Sun God Re. The serpents Mehen and Mehenet are solar powers and Their coiling and encircling protects.

There was a tradition at Dendera that Dendera is the birthplace of Isis. An inscription in the sanctuary there says that Isis’ “mother bore Her on earth in Iatdi [that is, the Temple of the Birth of Isis at Dendera; also another name for Dendera as a whole] the day of the night of the infant in His nest.* She is the Unique Uraeus . . . Sothis in the Sky, [female] Ruler of the Stars, Who Decrees Words in the Circuit of the Sun Disk.” Since Isis is also Sopdet/Sothis/Sirius, the heliacal rising of the Goddess in Her star, just before sunrise, is Her “birth.” Her birth precedes the rebirth of the falcon Re—”the infant in His nest”—as He rises in the sun on the first day of the New Year.

The birth of Isis is also connected with the seshed band. We learn that the “Ritual of Presenting the Seshed Band” takes place on “the Day of the Night of the Child in His Nest.” These seshed bands, presented to Isis for a happy New Year, included inscriptions like “A beautiful year—a million and a hundred-thousand times” and “A happy year, year of joy, year of health, eternal year, infinite year.” In addition to offering the seshed band on Isis’ birthday, it was also given on the first day of the New Year.

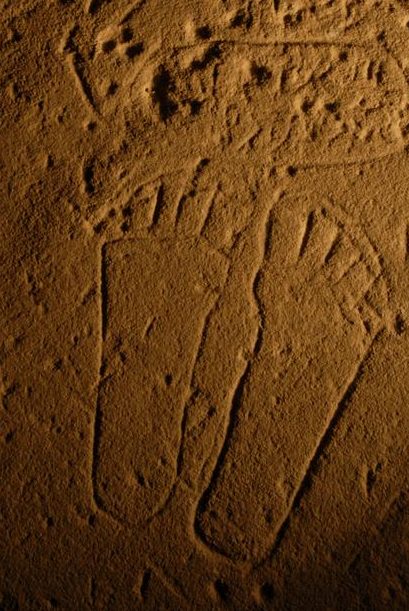

The seshed band must have been—at least originally—a fabric band, for it was tied around the head and knotted with the two long ends of the band hanging down in back. The knot at the back was surely intended to be magical, emphasizing the ability of magical knots to secure and protect, while the band itself surrounds and protects like Mehenet.

The Pyramid Texts mention a powerful red headband with which the deceased identifies. Another Pyramid Text mentions a red and green headband that was woven from the Eye of Horus. While some Egyptologists connect these headbands with the seshed, I can’t be sure because I’m only looking at the English translation of the texts.

However, from Dendera, we do have an inscription that specifically describes a seshed band made of electrum. It is also possible that the fabric headbands had metal pieces, suitable for engraving with blessings, attached to them. It seems likely that the serpent that entwined the seshed would have been made of metal.

Egyptian Egyptologist Zeinab El-Kordy suggests that the word seshed is the active participle of shed, meaning “to draw or pull out” or “to cause to come.” She therefore connects it with drawing the Inundation out from its source and causing the flood to come. This could mean that the seshed band, especially when offered at the birth of Isis and the New Year, is a magical tool for helping to bring the much-desired Nile flood.

The seshed band protects and unifies. It is given as a talisman for New Year’s prosperity—which I think we can easily extend to good luck and blessings in general. And it is associated with rebirth and renewal. We also have scenes that connect it with birth as well as rebirth. They show the birthing mother, her midwives, and protective Birth Goddesses like Isis, Taweret, and Hathor, all wearing seshed bands.

Given this, I would suggest that if we are working with Isis in any of these areas—protection, unification, birth, rebirth, renewal, and even good fortune and good outcomes in general—we would be eligible to wear the seshed as part of our ritual gear. Although a custom-made uraeus serpent is probably out of reach for most of us, a fabric band in red (power and protection) or green (growth, change, benevolence) with a piece of inexpensive serpent jewelry attached to it, would be a perfectly serviceable seshed band for our work with Isis.

* Sources such as the Cairo Calendar connect the Night of the Child in His Nest with the 5th epagomenal day and the birth of Nephthys, while Isis’ birth is on the 4th epagomenal day. But at Dendera, Isis must have been considered to have been born on the 5th and last epagomenal day, rising as Sothis just before the sun. When the sun rises, the 5th epagomenal day officially ends and the new day and New Year begins. As is so often the case with Egypt, the myths and traditions could vary from place to place.