Last night, we held our All-Hallows Eve rite (a bit early, I know). As we welcomed our Honored Dead in the presence of the Dark Ones, many of us were very aware of the bright moon shining above, just two days past a full Hunters’ Moon.

The moon, the moon, the moon. And I am thinking now of the moon and Our Lady Isis.

When we first encounter Isis, we often first discover Her as a lunar Goddess, a Goddess of the Moon. But is She?

Well, that really kind of depends on when you ask.

If we’re asking for today, for now, then yes, She is. And She has been for more than a millennium. But She took a rather circuitous route to get there. So let’s follow that trail a bit and see how it happened.

Early in Egyptian history, Isis was firmly associated with the heavens—with the star Sirius in particular, and with the sun, too—but She was not considered a Moon Goddess.

Moon Gods were the norm for Egypt—Iah, Thoth, Khonsu, and Osiris are among the most prominent and the moon’s phases were quite important to the ancient Egyptians. Scholars generally agree that the first Egyptian calendars, like those of so many ancient people, were lunar based. The temples marked the moon’s changes and especially celebrated its waxing and full phases. But the face the Egyptians saw in the moon was masculine rather than feminine.

For example, the waning and waxing of the moon could be associated with the wounding and healing of the Eye of Horus. So, perhaps we can think of Isis as the Mother of the Moon. Indeed, She was called “Isis, Who Creates the Moon Eye of Horus by Her Heart.” In some myths, Isis is the one Who heals Horus’ Eye, in others, it is Thoth or Hathor and we see this reflected in Isis’ epithet as She “Who Heals the Left Eye.”

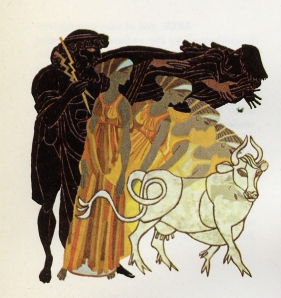

By the time of the New Kingdom, the beloved of Isis, Osiris, becomes prominent as a lunar God. We have a number of examples of statuettes of Osiris-Iah—Osiris assimilated with Iah, a Moon God—or simply as Osiris the Moon. So in this case, Isis is married to the Moon. But She’s not really a Moon Goddess Herself.

On the other hand, the Greeks and the Romans were all about the Moon Goddess. In fact, the moon itself was simply called “the Goddess.” People spoke of doing something “when the Goddess rises.” They would kiss their hands, extending them toward the rising moon, “to greet the Goddess.” Magical texts give instructions for performing a certain ritual “on the first of the Goddess,” meaning at the new moon. When they saw Isis with Her horns-and-disk crown, they saw a Moon Goddess.

And because we have so much information about Isis from these Moon Goddess-loving people, today when many people think of Isis, the moon is one of the first things they associate with Her. Yet, interestingly, it seems to have been a third century BCE Egyptian priest named Manetho who first connected Isis with the moon. By the following century, when Plutarch recorded the most complete version of the Isis-Osiris myth we have, the tradition of Isis as a Goddess of the Moon was firmly established—even in Egypt.

Of course, it was easy to associate the fertility-bringing moon with the fertile Mother Isis. The ancient world also associated love affairs with the moon (the romance of moonlight, you know) and, in Her passion for Osiris, Isis was a famous lover.

Of course, the moon and the obscuring darkness of night were connected with magic, too—and Isis was one of Egypt’s Mightiest Magicians from the beginning. She was called Lady of the Night. One Egyptian story told how a particular magical scroll—which the tale calls a “mystery of the Goddess Isis”—was discovered when a moonbeam fell upon its hiding place, enabling a lector priest in Isis’ temple to find it.

Today, we also connect the moon with emotions, the deep, the waters, the feminine (taking our cue from the ancient Greeks and Romans), the home, Mystery, and change (to name but a few). And Isis can definitely be associated with all of these things—from the emotional passion of Her myths to Her ancient Mysteries and Her enduring role as the Goddess of Regeneration and Transformation.

So is Isis a Moon Goddess? She certainly has been for a very, very long time. Whether we choose to honor Her in this form has more to do with us than with Her. Many contemporary Pagans will probably be quite comfortable working with Isis as a Moon Goddess; a strict Kemetic Reconstructionist, not so much. But Isis is a Great Goddess; She is All, and so, for me, She is unquestionably to be found in the deep and holy Mysteries of the Moon.

And yet, and just for myself, while I do find Her in the moon, I resonate most strongly with Isis of the Stars and Isis of the Eternities of Space and Isis the Radiant Sun Goddess. Nevertheless, I still feel the call to explore Her important lunar aspects. What about you?