Every year, about this time, I learn from various and sundry newspapers and journals across the land, that Mother’s Day originated in the worship of the Egyptian Goddess Isis.

The idea seems to be that Mother’s Day developed from the ancient worship of Mother Goddesses. And since Isis is THE most well known of these ancient Goddesses, then Mother’s Day had to be Hers, right?

Sorry. Nope. (You can learn the real story, at least as far as the US is concerned, here.)

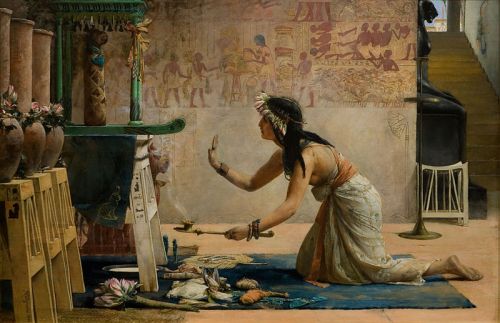

But, of course, Isis is a Mother Goddess and many, many people have grown their relationship with Isis in Her motherly aspect. So today, in honor of Mother’s Day, I’d like to share with you some lines from a particularly interesting New Kingdom hymn to the Great Goddess.

See if you can guess which Goddess the hymn praises. (When you see […] in the text, it means that the words there could not be read because the source was too damaged.)

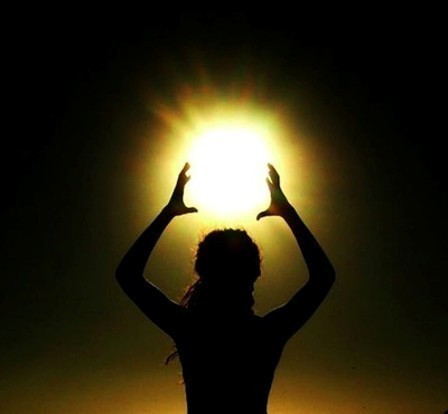

“…great of sunlight, Who illumines [the entire land with] Her rays. She is His Eye, Who causes the land to prosper, the glorious eye of Harakhti, the Ruler of What Exists, the Great and Powerful Mistress, life being in Her possession in this Her name […]

[…] in the circuit. The Gods are in […] Great of Might. Her Eye has illumined the horizon. The Ennead, Their hearts are glad because of Her, the Mistress of Their Joy, in this Her name of Heaven.

She is in their hearts, they being glad when She ascends to Her abode, Her temple. She has appeared and has shone as the Woman of Gold […] of best pure silver. All lands give Her their divine property in Her name, and their standards of their places. They rejoice for Her and Her beauty which belongs to Her. Everyone comes into existence through Her when he is created, say the Living in this temple.

There exists no one like Her on earth. She who lives by the might of Her word.

[…] the Great One of the Throne […] She is […] of forms, Great of Property, Mistress of That Which Exists. The papyrus flourishes.”

This Goddess is also called Mistress of the Gods, Queen of Heaven, Great Goddess, Mighty Goddess, Lady of the Two Lands.

While this hymn could well have been used to praise Isis, it wasn’t. It seems that all the Great Goddesses, at one time or another, were called by each other’s epithets and even by each other’s names. Louis Zabkar, who has studied the Isis hymns at Philae extensively, traced how a number of the texts at Philae were adapted from preexisting sources to suit both the space they had available at Philae and the Goddess they were praising.

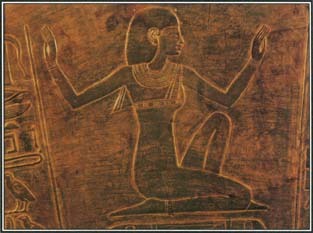

Yet this particular hymn is in praise of Mut; and it is especially interesting because it is in the form of a crossword. Known as the Crossword Hymn to Mut (obviously enough), the instructions say to read it “three ways.” Indeed, it can be read horizontally and vertically. Scholars guess that the third way might be around the edges, but the artifact is too damaged to be sure that works.

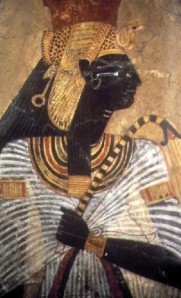

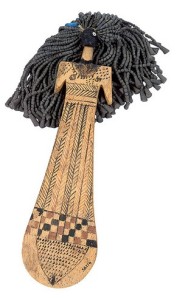

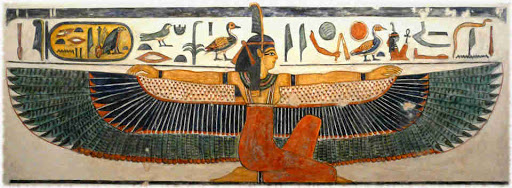

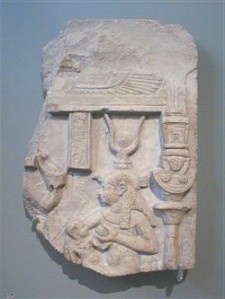

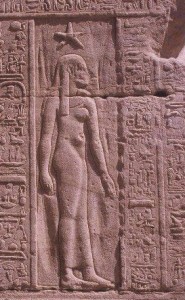

Mut’s name means simply “Mother.” It is spelled with the vulture hieroglyph, which also connects Her with one of the Two Ladies of Egypt, Nekhebet the Vulture Goddess Who was the protectress of Upper Egypt.

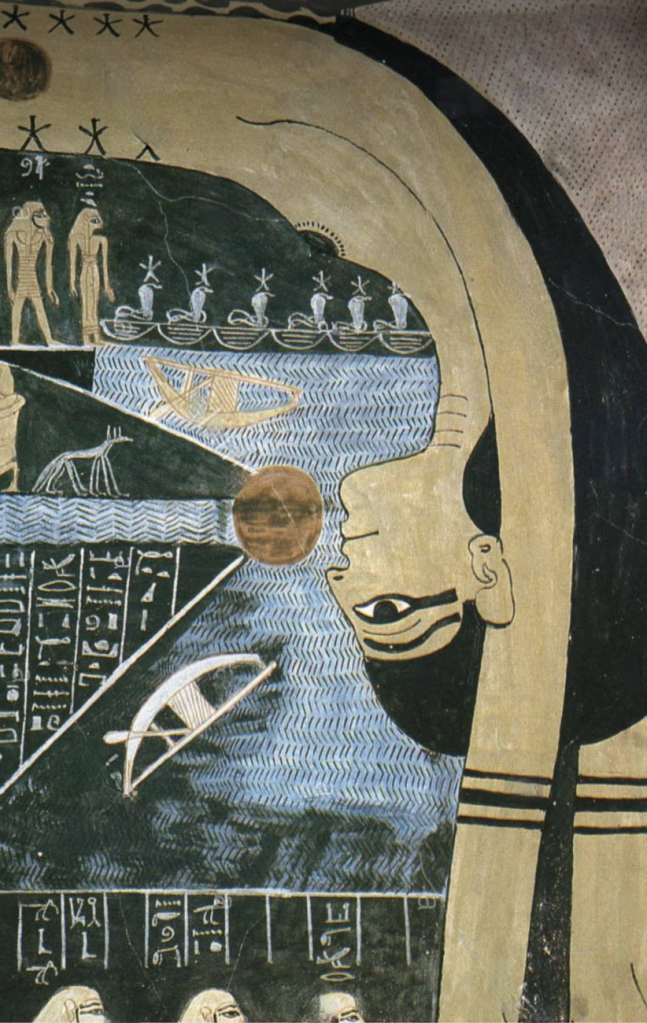

According to Horapollo, supposed to be an Egyptian priest or grammarian of the fourth century CE, Egyptian tradition had it that there were no male vultures. Female vultures were thought to remain virgin, but to become pregnant by exposing their vulvas to the north wind. (The north wind was associated with the coming of the inundation and thus with fertility.) Thus Mut is a Virgin Mother. In Her Crossword Hymn, we see Her both as the maiden Daughter of Re and the Great Mother, since everyone comes into existence through Her.

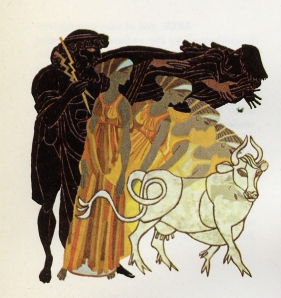

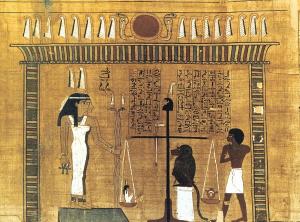

But Mut also has a powerful lioness aspect. In this form, She is one of the Raging and Returning Goddesses, like Sakhmet, Hathor, and Tefnut. In the Book of the Dead, Spell 164, a magical image of Mut is described as having three faces: a vulture, a woman, and a lioness. Not only that, She has a phallus and wings and lion’s claws. The Crossword Hymn shows Her as a fierce and awesome Mother when protecting the dead. Yet it also calls Her Mistress of Joy, Mistress of Peace, and the Beloved One.

Of course, Isis, too, is a Mother Goddess. Specifically and significantly, She is the mother of Horus, Mut Nutdjer, “Mother of the God.” But She also reveals Herself as Mother of the Gods and as the Great Mother of All. As a Great Mother, Isis has inspired the devoted worship of people throughout history. During the Græco-Roman period, Isis’ motherliness toward humanity was expressed in the novel The Golden Ass by Her initiate, Lucius, who declared that Isis brings “the sweet love of a mother to the trials of the unfortunate.” This conception of Isis endures today when, for many, Isis is the very model of the Mother Goddess.

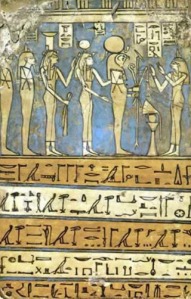

It should be no surprise then that Mother Isis and the Goddess Whose name is simply “Mother” would become identified. In Isis’ Roman-era temple at Shenhur, Isis is represented in four forms: as “Isis the Great, Mother of the Gods,” as “The Great Goddess Isis,” as Mut, and as Nephthys Nebet-Ihy (a festive form of Nephthys). In Mut’s Crossword Hymn, Mut is said to be “under the king as the throne,” just as Isis’ very name means “Throne.”

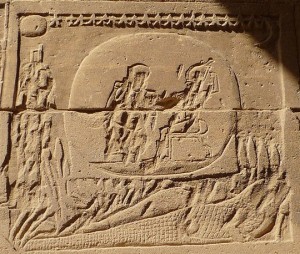

As Isis the Kite protects Osiris by enfolding Him in Her wings, so in one of the Books of the Dead, a vulture-headed Mut is shown enfolding Osiris in the same way. On a pectoral found in Tutankhamon’s funerary equipment, a vulture, labeled “Isis”, guards the king.

In the Book of the Dead, the “vulture of gold” to be placed at the neck of the deceased is associated with Isis. Both Isis and Mut wear the Vulture Headdress, though Mut wears over it the combined Red and White Crowns. Both are Eye Goddesses and Uraeus Goddesses and as such are assimilated with Bast and Sakhmet. Both, as Great of Magic, take the prominent place of the divine barque to defend and protect the Sun God. And of course, both are Divine Mothers; Isis of Horus and Mut of Khonsu. Isis and Mut are considered to be the mother of the pharaoh and They ultimately mother those of us devoted to Them.

I started this post because I wanted to share with you the amazing Crossword Hymn of Mut. But as I write, I am again struck by this idea of the correspondences between the Great Goddesses of Egypt (and the Great Gods, for that matter). They share mythology. They share epithets. And They share the ability to appear as each other “in Her name of fill-in-the-blank.” This capacity, along with the ancient Egyptian idea that the Deities could combine Their identities or be the Ba-soul of another Deity points at an underlying unity of the Divine in the midst of a thriving polytheism.