Today’s post is a repost. I really just needed to offer something not topical (my brain and soul are a bit ragged right now), but which shows how very topical our Goddess Isis has been throughout Western history.

Have a bit of respite from the news and enjoy…

Did you know that Isis can be connected with Queen Elizabeth I—she for whom the “Elizabethan Age” is named?

It’s an interesting story…

It’s a story that speaks to the influence of Isis’ story throughout the ages. It is also a story that reinforces Isis’ importance as a feminist icon.

So let us start in 1558, the year Elizabeth, daughter of Henry VIII, became queen. Elizabeth never married, thus never shared her throne; she reigned for over 40 years. She was called “Gloriana” and “Good Queen Bess” and “the Virgin Queen”.

But this whole unmarried-queen-ruling-by-herself thing was problematic. If you think there’s sexism now, imagine 1558. Even queens were not immune. Elizabeth’s advisors were forever pestering her to marry. It was a given that women were inferior in all ways, from moral strength to intellectual strength to physical strength. “Frailty, thy name is woman,” sayeth the Bard in Hamlet to absolutely no one’s surprise. Women had virtually no rights under the law and were subject in all things to first father, then husband.

1558 was also the year that John Knox published his polemic against women rulers called The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regimen [that is, “rule”] of Women. It was specifically against the Catholic queens of Scotland and England (Knox was Protestant), but as Elizabeth came to the throne in the same year, you can be sure it was applied to her as well. Knox summed up the general attitude this way:

For who can denie but it repugneth to nature, that the blind shal be appointed to leade and conduct such as do see? That the weake, the sicke, and impotent persones shall norishe and kepe the hole and strong, and finallie, that the foolishe, madde and phrenetike shal gouerne the discrete, and giue counsel to such as be sober of mind? And such be al women, compared unto man in bearing of authoritie. For their sight in ciuile [civil] regiment, is but blindnes: their strength, weaknes: their counsel, foolishenes: and judgement, phrenesie, if it be rightlie considered.

As you might expect, Elizabeth took offense and she opposed Knox, successfully keeping him from being involved in his beloved “Protestant cause” in England. Queens do have some power after all.

What Elizabeth needed was some propaganda of her own. So she carefully constructed her public image, sometimes by portraying herself as the mother of her people, sometimes as a king or prince, and sometimes by having herself compared to various Goddesses—Goddesses Who were thought, by this time, to be safely in the past. This meant that Their myths could now be used to portray queenly and Protestant values without too much consternation.

Sir Walter Raleigh wrote a long poem that helped promote the cult of Elizabeth as the Virgin Moon Goddess Diana. During royal functions as well as in Elizabeth’s raiment, the liberal use of the symbols of the moon and moon-like pearls helped promulgate the idea.

As war leader of her people, Elizabeth would style herself after Minerva, a Goddess capable of war, but more known for Her wisdom and love of peace. While addressing troops who were preparing to repel the Spanish Armada, she wore an Minerva-like plumed helmet and steel cuirass over a white velvet gown. She turned sexism on its head with the most famous line of her speech: “I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too…”

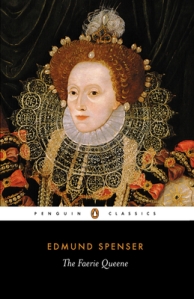

Then in 1590, Edmund Spenser wrote a long, highly allegorical poem called The Faerie Queene, which he dedicated to Elizabeth and in which he symbolically portrays his queen through various characters in the poem, including Gloriana, the Faerie Queene of the title. The poem is classic sword-and-sorcery, knights-and-damsels; Elizabeth liked it enough to award Spenser a pension for life.

It is in The Faerie Queene that we meet Isis as a symbol of Justice and equitable queenly rule. Spenser wanted to associate Elizabeth’s rule with an ancient Golden Age ruled over by another strong queen: Isis, the Divine Queen of Egypt. Spenser tells us that Isis was “a Goddess of great powre and souerainty” and that justice and equity were among Her blessings. So too are power, sovereignty, justice, and equity hallmarks of Elizabeth’s reign. Elizabeth is further associated with Isis—as well as with the famous Queen Cleopatra—by the fact that the Faerie Queene lives in “Cleopolis.”

In support of his Faerie Queene, Spenser writes that during recent history men had not properly recorded the deeds of women rulers, particularly their deeds of war. However, in ancient days (such as the time of Isis) female rulers were given the credit they deserved. He also explains that men’s jealousy of women caused them to “curb women’s liberty.”

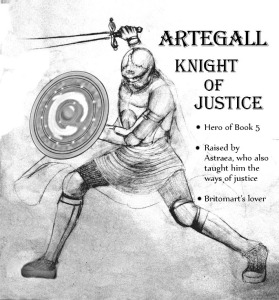

Scholars think that we are seeing the influence of the Hermetica as well as Giordano Bruno’s Egyptian-themed work on Spenser’s choice of an Isis-and-Osiris theme in Book V of the poem. Britomart, the female Knight of Chastity, is Isis-like, while the male Knight of Justice, Artegall, is Osiris-like. They are lovers, separated by various adventures, which require Britomart to search repeatedly for Artegall just as Isis does for Osiris.

We see Britomart at her most Isian in Book V, Canto VII of the poem as she sets out to rescue Artegall from the evil Amazon queen Radigund. (Yes, it’s not all that feminist a poem.) Along the way, Britomart stops to rest at a temple of Isis (also called “Isis Church” in the poem) and is received there by the priests. The long-haired priests, dressed in silver-trimmed linen robes and moon-shaped headdresses, are in the midst of their offering rites. Britomart is amazed by the beauty of the temple, gawking openly.

The priests take her to the sacred image of Isis, which is as beautifully wrought as the temple itself. The image is crowned with gold “to shew that she had powre in things diuine”, carries a wand, and with one foot treads upon a crocodile that represents both “forced guile and open force” and is being suppressed by Isis.

Britomart kneels down and prays at the Goddess’ feet. The wand in the hand of “the Idoll” moves, which Britomart takes as a sign of good fortune and falls asleep: “There did the warlike Maide her selfe repose, Vnder the wings of Isis all that night…” The priests, too, went to sleep and “on their mother Earths deare lap did lie.” They kept strict chastity and eschewed both meat and wine (especially wine).

Now Britomart dreams a dream that foretells her fate. She sees herself, as a priestess, making sacrifice to Isis. Then her linen robes becomes scarlet and her headdress becomes a crown of gold, like that of the Goddess Herself. She is in wonder, yet pleased by the change as she becomes merged in Isis. Suddenly, a wind arises that fans the altar flames and threatens to set the temple on fire. The crocodile beneath the foot of the sacred image of Isis comes to life, devours the flames and the wind, and starts toward Britomart. The image of Isis raises Her wand and beats him back.

Chastised, the crocodile now humbly comes to Britomart, begging her to love him. Which she does, becoming pregnant with and then giving birth to a great lion that subdues everything. (How’s that for a dream, eh?)

At that, Britomart wakes, confused and upset. The priests are already up, preparing for the day. Their leader notices Sir Knight’s dismay and asks her about it. She tells him the dream.

Immediately, he sees that she is of royal blood. He tells her that the crocodile represents Artegall and also the just “Osyris” Who sleeps forever beneath Isis’ foot, protected from those “cruell doomes of his.” The priest tells her that she and Artegall will have a lion-like son and start a dynasty. (Elizabeth, of course, is of this heroic line.) After rewarding the priests with gold and silver as gifts for their Goddess, the knight continues on her way.

According to Spenser’s tale, other heroes are also part of Elizabeth’s heritage, including King Arthur, the British warrior queen Boudicca, and the Anglo Saxon heroine Angela. Yet the story of Isis and Osiris, associated with Spenser’s greatest virtue, Justice, is especially important.

Though Britomart and Artegall reign with great justice for many years, eventually, Artegall is killed—by treachery—and taken from Britomart just as Osiris must eventually leave Isis to rule in the otherworld. Yet before he dies, they conceive a son, a Horus-Child who will begin the dynasty destined to lead to the reign of Elizabeth, the royal virgin who marks the glorious culmination of the Britomart-Isis and Artegall-Osiris line.