I don’t know whether I believe in reincarnation; at least in the usual contemporary sense. Oh, I like the idea of it…and it’s quite true that there are some amazing stories people tell of past lives.

Egyptologists, however, are almost unanimously certain that the ancient Egyptians did not believe in reincarnation; presumably, they had enough going on in their afterlives already.

On the other hand, we do have ancient Greek reports of Egyptian belief in reincarnation or the “transmigration of the soul.”

Herodotus writes,

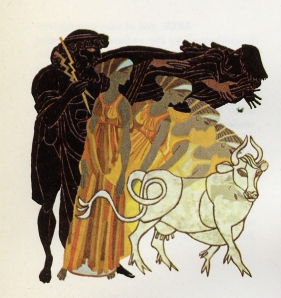

The Egyptians say that Demeter [that is, Isis] and Dionysos [that is, Osiris] are rulers of the world below; and the Egyptians are also the first who reported the doctrine that the soul of man is immortal, and that when the body dies, the soul enters into another creature which chances then to be coming to the birth, and when it has gone the round of all the creatures of land and sea and of the air, it enters again into a human body as it comes to the birth; and that it makes this round in a period of three thousand years. This doctrine certain Hellenes adopted, some earlier and some later, as if it were of their own invention, and of these men I know the names but I abstain from recording them. (Herodotus, Histories Book II, 123)

Diodorus Siculus also reported prominent Greeks who adopted Egyptian teachings, including the transmigration of the soul:

Lycurgus also and Plato and Solon, they say, incorporated many Egyptian customs into their own legislation and Pythagoras learned from Egyptians his teachings about the gods, his geometrical propositions and theory of numbers, as well as the transmigration of the soul into every living thing. (Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Book I, 98)

Plutarch mentions it, too:

The Egyptians, believing that Typhon was born with red hair, dedicate to sacrifice the red coloured oxen, and make the scrutiny so close that if the beast should have even a single black or white hair, they consider it unfit for sacrifice; because such beast, offered for sacrifice, is not acceptable to the gods, but the contrary (as is) whatsoever has received the souls of unholy and unjust men, that have migrated into other bodies. (Plutarch, “On Isis & Osiris,” 31)

It may be that Herodotus misinterpreted the post mortum transformations of the dead (“Becoming a Hawk of Gold,” for example) as transmigrations of the soul. It may be that Diodorus and Plutarch, writing after Herodotus, just picked up his idea.

Empedokles, a contemporary of Herodotus, refers to “polluted daimons” who are forced to wander the world in many forms “changing one toilsome path of life for another,” though he does not refer to this as being an Egyptian conception. (Empedokles, Katharmoi)

In a number of his works, Plato mentions transmigration as punishment that souls suffer for bad deeds in life. The idea entered the Roman world as well. It can be seen in Virgil’s Aeneid, where reincarnation was seen as a reward for a good soul rather than a punishment for a bad one.

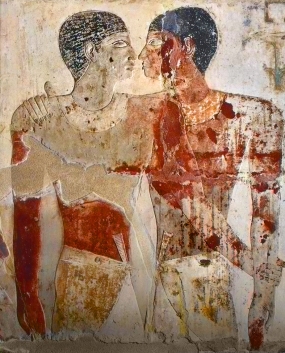

For the Egyptians, the transformations of the dead were simply part of an active and happy afterlife. The dead could become a hawk, a lotus, a serpent…and godlike. Louis Zabkar (an Egyptologist who made an important study of the Isis hymns at Philae) believes that this was a way of ensuring the ba of the person had unlimited freedom to come and go at will on earth and in the otherworld.

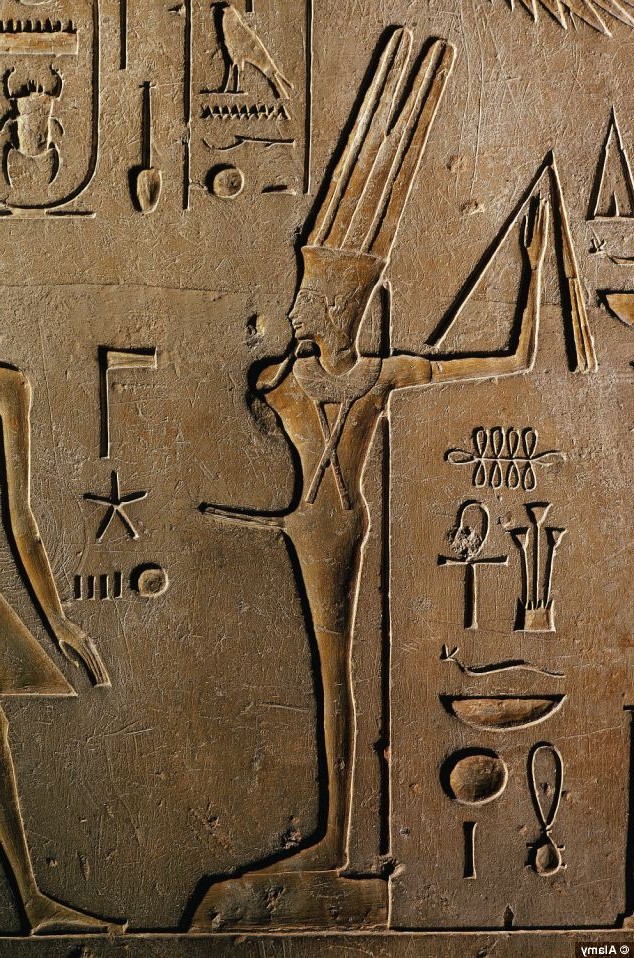

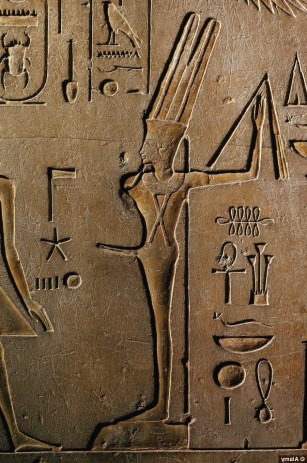

Several pharaohs took the name Repeater of Births, which sounds like a reference to reincarnation, but probably isn’t. For Seti I, it apparently meant that he intended to usher in an Egyptian renaissance of sorts. Or it may have referred to the pharaoh’s divine rebirths, which occurred at certain festivals of renewal, or to the the king’s connection to the Sun God Re Who is reborn daily.

All that said, I’d like to share with you one of my (possible?) past life stories.

During a vacation period a while ago, I had the luxury of frequent invocation of the Goddess. While working the Opening of the Ways ritual, I “saw” a flash of a scene that had a deju vu feeling about it, so I decided to follow up on that vision with Isis. Under Her wings, I traveled back in the Boat of Millions of Years to locate the life that included the scene that had touched me. Here is that tale…

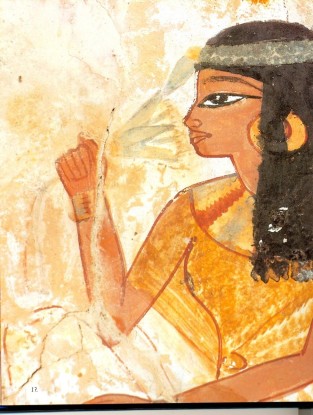

A woman of about 20 is looking out across the Alexandrian harbor. Her name is Ankesphilia and she is the priestess of the Pharos, the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Her duty is to perform something like the Opening of the Ways ritual—but for the opening of the Alexandrian harbor and for fair, “open” weather. This is done within the Pharos itself, about halfway up the structure. That’s where the scene that first caught my attention is from: halfway up the Pharos, overlooking the harbor.

And while Isis is the Goddess of the Lighthouse, it is not Isis who is in Ankesphilia’s heart. Instead, it is her duty to the city that occupies her. Ankesphilia has almost no personal freedom and must stay on Pharos Island at all times, except when there are great festivals in the city. Then she may go to see the processions. I have the feeling that she was “given” or vowed to the Pharos, though it was not her own vow; perhaps her parents? In a way, it reminds me of the later Christian anchorites.

The priestess is from a wealthy, but not noble, family. Her parents own a shipping business, but now her father has retired to the priesthood and her mother runs the business. Her father sometimes visits Ankesphilia at the Pharos. She rarely sees her mother. She has two brothers, both in the military. Though she has had no choice in her fate, I sense no rebellion or resentment in her. I have the feeling she is perhaps not very well educated, bright, or curious. She simply does the duty that has been given to her without complaint and with conscientiousness.

Ankesphilia died in her 30s after contracting a disease that came into the harbor city from overseas.

And that’s it. Past life? Fantasy? I don’t know, but either way, it tells me something about myself.