The Key to Egyptian Magic, Part 2

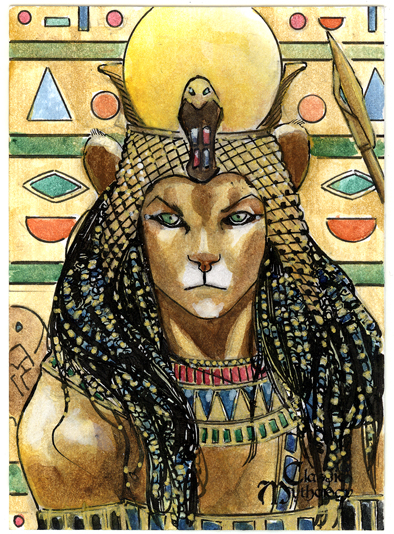

Last week, we talked about Kheperu or “Transformations” as the key to Egyptian magic. This is the technique by which a human magician, priest/ess, or other adept practitioner, may briefly partake of Divine powers through the use of sacred images, ritual speech, and right action. It is a way of empowering our magic.

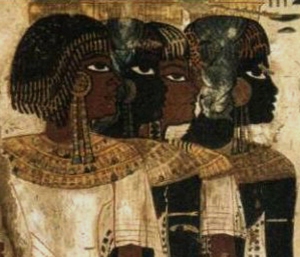

To develop this technique, a society would need to understand that human beings could become godlike—which ancient Egypt did—and further, that human and Divine beings naturally interact with each other and mutually affect each other.

This is a magical and participatory world. In Jeremy Naydler’s book The Temple of the Cosmos, he comments that the Egyptians believed human beings depended on the Deities, but that the Deities also depended on human beings—even to the extent of relying on human action to help mobilize heka (“magic”) in the universe through the temple rites. Both Deities and humanity must uphold Ma’et (“Rightness,” “Truth”) or the universe will be thrown into chaos. Thus human beings have an innate power and influence, although we cannot hope to match that of the Goddesses and Gods. In this world view, it is theoretically possible for a human being—especially one who had acquired a lot of heka, because one can acquire it—to cause change or even chaos in the universe. If humans are part of the universal order, we can affect the universal order.

This interconnectedness is why we sometimes find threats made against the Deities in Egyptian magical formulæ. This was one of the things that freaked out Greek magic workers when they encountered it. To them, claiming godlike power was hubris—and the Gods were sure to smack you down for it rather than help you out.

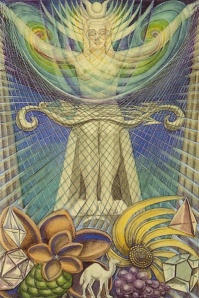

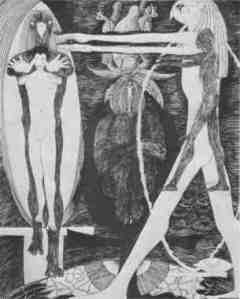

Nuet, the Heavens, joined to Geb, the Earth

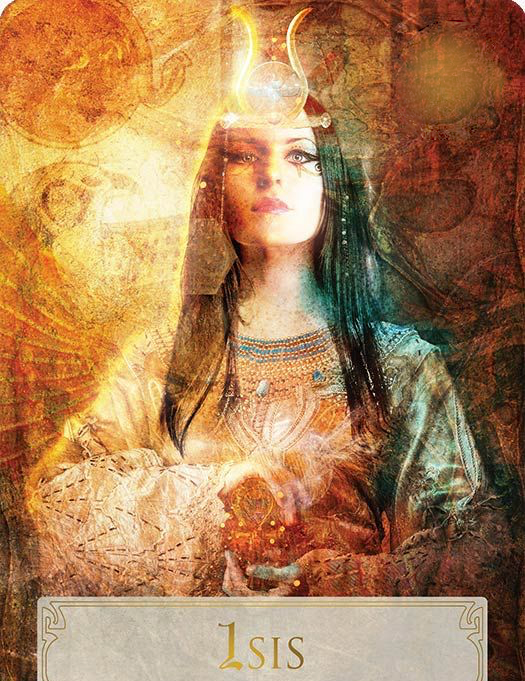

Yet the idea that human beings have the power to affect the universe stems from the interrelatedness and interdependence of the human and the Divine worlds in Egyptian tradition. In the same way that the Great Goddess of Magic, Isis, threatens to stop the Boat of the Sun in its tracks unless Her son Horus is healed, so the human magicians sometimes threatened the Deities with a similar upset to the cosmic order unless their desires were met. “The expertise of the magician lay in bringing together the spiritual and material levels in a deliberately engendered and powerful coalescence. Magic did not function exclusively on the physical or the psychic or the spiritual planes but on all three together,” writes Naydler. And a most effective way of joining all three worlds is through the technique of Kheperu.

Some Examples of Kheperu

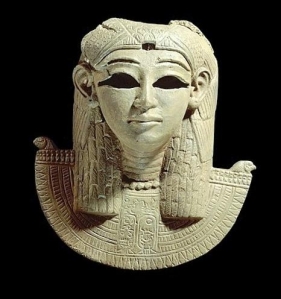

In his excellent study, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt, the One and the Many, Egyptologist Erik Hornung defines Egyptian Deities by three criteria: Onoma (the name of the Deity), Logos (words or knowledge about the Deity), and Eidolon (the image of the Deity). All three, combined with ritual, are also used in Kheperu as we see it expressed in Egyptian texts.

A longish passage from the Coffin Texts illustrates these principles and highlights some of the characteristics of Kheperu (CT Formula 484, Faulkner translation):

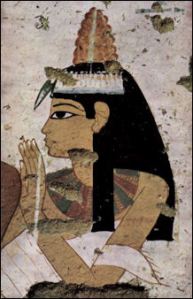

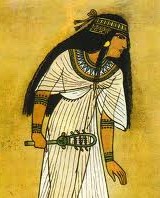

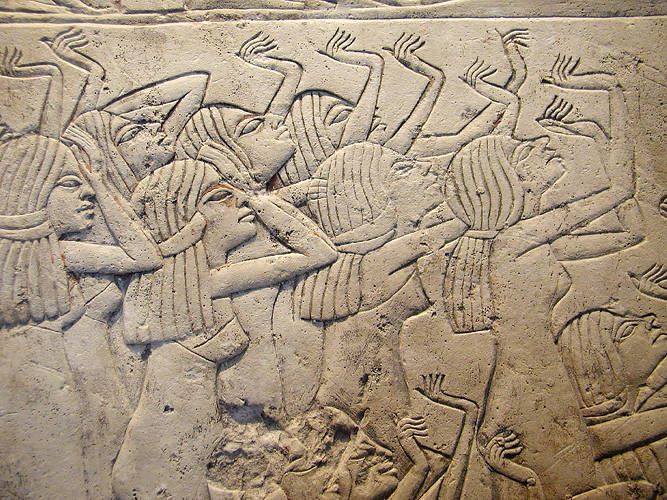

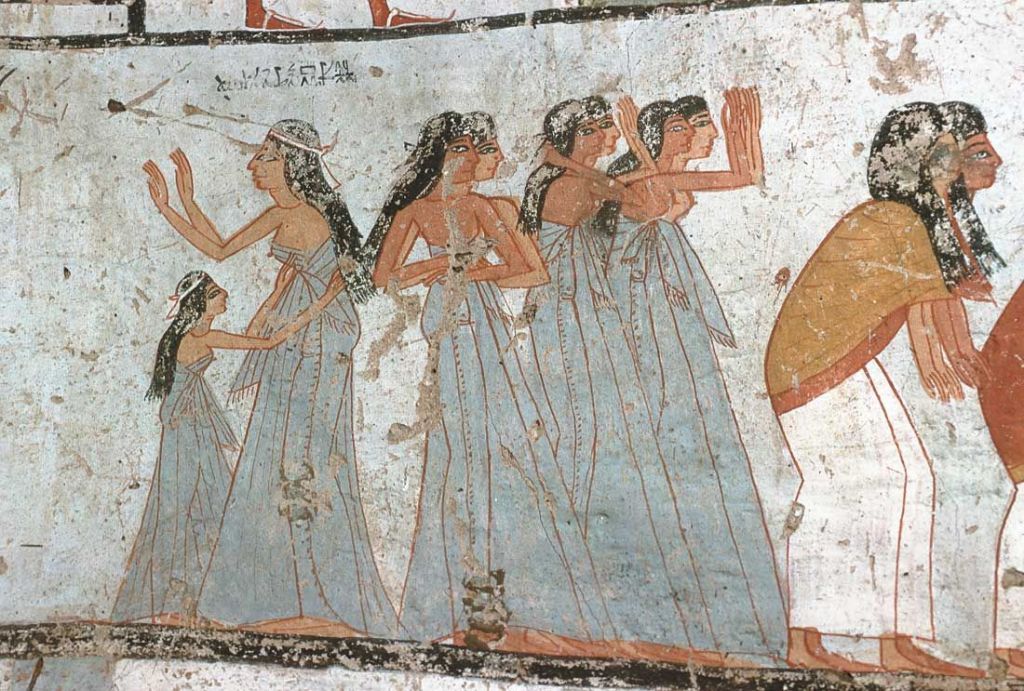

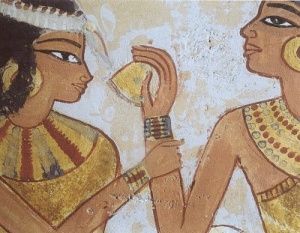

“The Sistrum-Player is in my body, the pure flesh of my mother, and the dress will enclose me. I don the dress of Hathor, my hands are under it to the width of the sky, my fingers are under it as living uraei, my nails are under it as the Two Ladies of Dep, and I kiss the earth, I worship my mistress, for I have seen her beauty. She creates the fair movements which I make when the Protector of the Land comes; the gods come to me bowing and praise is given to me by the gods, they see me at my duty, and I am initiated into what I did not know, I cross the retinue of this Great Lady to the western horizon of the sky, I speak in the Tribunal. [. . .]

“The god who protects the land comes,” say the horizon dwellers concerning me. “The god comes, having gone aboard the bark,” say they who are about the shrine, who sit in the sides of the bark, who eat their food. They see me as the Sole One with the secret seal. I don the dress, I wear the robe, I receive the wand, I adorn the Great Lady in her dignity. Her Sistrum-Player is on her lap, and he has built mansions among your great ones, he has presented offering cakes, so that he may live thereon and that he may celebrate the monthly festival in his hour in company of those who are in linen, for he has looked at his face. So says the occupant of the throne of the Great Lady concerning me.”

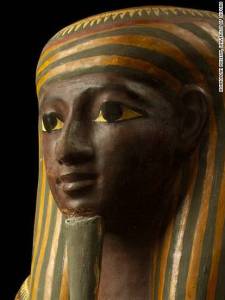

We can be sure that the deceased is intended to be in the Kheper of Form of the Goddess because when he “dons the dress of Hathor,” “the Sistrum-Player is in my body,” and it is She Who “creates the fair movements which I make,” and the horizon dwellers “see me as the Sole One with the secret seal.” He employs the Onoma, the names and epithets, of Hathor in his formula. He has knowledge of Her Logos for he describes Her place in the sacred barques of the Gods. He also uses Her Eidolon, symbolized as the dress of Hathor, building up the Goddess’ image through the description in the text and putting on Her dress or image.

As in this example, Kheperu is often characterized by a multiplied consciousness. Here, the deceased perceives as a human being, as Hathor, and as Her son, the Sistrum-Player. The deceased is at once the Great Lady, Her Divine Child, and Her worshipper. So can we be both human being and Divine Being, mediating between Heaven and Earth, partaking of and blending both.

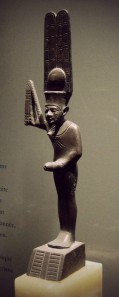

Another excellent example is a Coffin Text formula “for the Soul of Shu and for Becoming Shu” (CT Formula 228, Faulkner translation):

“I am the soul of Shu the self-created god, I have come into being from the flesh of the self-created god. I am the soul of Shu, the god invisible of shape, I have come into being from the flesh of the self-created god, I am merged in the god, I have become he.”

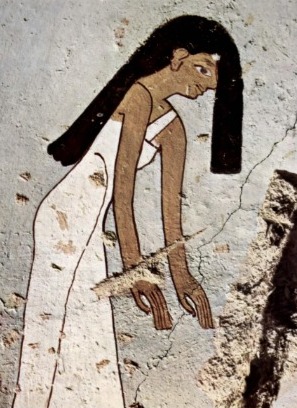

In the rest of this formula, the magician spends considerable time making statements that identify them with Shu. The magician recites the full myth of Shu, and beautifully ends the formula with “I am invisible of shape, I am merged in the Sunshine-God.”

In the following example, the deceased is identified with Re, quality by quality—which allows ample ritual time for visualization (Book of the Dead, Formula 181, Faulkner translation):

“His sun disk is your sun disk;

His rays are your rays;

His crown is your crown;

His greatness is your greatness;

His appearings are your appearings;

His beauty is your beauty. . .”

In Formula 78 of the Book of the Dead, the deceased says:

“Horus has invested me with his shape [. . .] I am the falcon who dwells in the sunshine, who has power through his light and his flashing. My arms are those of a divine falcon, I am one who has acquired the position of his lord, and Horus has invested me with his shape. “

Once the Kheper is assumed, the Deity could be perceived within: “Hail to you, Khopri within my body” states Formula 460 in the Coffin Texts.

I have no doubt that if you worked these spells today—as written and while in the proper frame of mind—you could indeed assume the Form of Hathor or Shu or Re or Horus…or, importantly for us, of Isis.

This is really a huge topic and, once again, I have taken up enough of your time for today.

One of the most important things about this technique is that it persisted. From ancient Egypt to the magic of the Greco-Egyptian Magical Papyri to the Hermetica to early Christian magic to Medieval magic to Qabalah and Christian mystics to modern ceremonial magic, Kheperu is there. And it is there because it works.

As the days grow longer, a certain soft joy fills me.

As the days grow longer, a certain soft joy fills me.