When the Christian Empire forcibly forbade the worship of the Pagan Deities, the Goddesses and Gods did not die. But They did go underground.

One place They hid was euhemerism, which is the idea that the Deities are merely historical mortals who, because of their special talents or moral worth, eventually came to be worshipped as Goddesses and Gods as Their stories became exaggerated over time. The concept is named after Euhemerus, a 3rd century BCE Greek mythographer. It wasn’t his original concept, but it is his name that became associated with it and here we are.

Euhemerism turned out to be not such an awesome idea because emerging Christianity could use it to ridicule Pagans for worshipping mere human beings. On the other hand, it did preserve the stories of the Goddesses and Gods far into the West’s Christian-ruled centuries. Since these stories were not really about Deities, you see, the stories could be told without being a threat to Christianity.

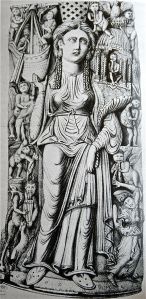

Churches and cathedrals of the Middle Ages were often decorated equally with images of Pagan Deities and Biblical characters. The sibyls of the Pagans and the prophets of the Bible were both considered people of wisdom from whom the churchgoer could learn. And while the Church wasn’t completely comfortable with this arrangement (and sometimes even railed against it) still the practice continued throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance.

In these stories, Isis is often seen as a culture-bearer and philosopher. In 1508, John Trithemius, the Abbot of Spanheim, lists Isis among the “men” who devoted themselves to the study of wisdom.

Verily in these times, as it evidently appears from the Histories of the Ancients, men more earnestly applied themselves to the study of wisdom, amongst whom the last learned and most eminent men, were Mercurius, Bacchus, Omogyius, Isis, Ianachus, Argus, Apollo, Cecrops, and many more, who by their admirable inventions, both profited the world then, and posterity since. (John Trithemius, De Septem Secundeis, A0-6)

Allegory was another refuge of the Pagan Deities. Allegory interprets the myths or attributes of the Pagan Deities as moral tales or philosophical concepts. Again, it was a method created by Pagans themselves to find additional meaning in their myths. The Neoplatonists of the late Pagan period used allegory as a method to refute the arguments of Christians who claimed moral superiority for their religion. Pagans could point to allegorical interpretations of the myths to show how Pagan myths taught honor, chastity, fidelity, and other virtues. Eventually, the myths of the Pagan Deities came to be used at least as often as Biblical stories to teach “Christian” values.

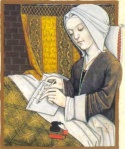

One of the writers who learned from the story of Isis was Christine de Pisan (1364—1430 CE). De Pisan was born in Venice, but spent her life in France. Writing in the Late Middle Ages, de Pisan was an early feminist (some say the first feminist, some prefer proto-feminist); her work challenged misogyny and the gender stereotypes of her day.

In a work called the Epistle of Orthea to Hector, de Pisan writes as the Goddess Orthea, a Goddess she created to represent the “Wisdom of Women,” to the young Trojan Hector, who represented the ideal knight. The Epistle consists of 100 stories meant to teach values to the young. All the stories are derived from Pagan texts from authors like Homer and Ovid. In one, de Pisan describes Isis (Ysys) as a planter and cultivator.

An illustration accompanying the text shows Isis grafting new branches on old trees. The knight is advised to follow the example of the Goddess and plant virtues in himself. The planting of these virtues is to be understood as similar to the conception of Jesus by the Blessed Virgin Mary, Whose “great bounties may be neither imagined nor said.” As was so frequently the case, here Isis is assimilated with Mary.

While we cannot claim that the worship of our Lady Isis is an uninterrupted tradition, I think we can rightfully claim that Isis never left human awareness. From the time when Her worship was forbidden to modern times when so many have returned to be sheltered in Her loving wings, Isis continued to live in myth, in allegory, in stories, in poems by first-feminist poets, in wisdom teachings, in alchemy, and in so many of the flowing streams of the Western Esoteric Tradition.

Isis is alive. The Goddess is alive. And yes, She always has been.