The Key to Egyptian Magic, Part 1

I admire the blogging work of John Beckett on Patheos. His recent post talks about the period of disruption we are in right now, which he (and some of his compatriots, I gather) call Tower Time, after the tarot card.

In this particular post, I was struck by his recommendation to magic workers to “take your magic up a notch” in response to current times. I do agree. As I said a couple weeks ago, this time of change, this time of flux, is precisely when magic can have an outsized effect.

So today I’m going to start a series on what I believe is THE key to Egyptian magic. It has no known Egyptian name, but you find it everywhere throughout Egyptian sacred written materials. It freaked out the Greeks when they learned about it from Egypt. And it still freaks out some modern magic workers.

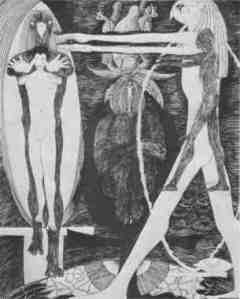

Here, let me demonstrate it:

I am Isis. I have gone forth from my house and my boat is at the mooring rope… O you who travel in the sky, I will row him with you, I will travel as Isis.

My name is Isis in the Sealed Place; I am in my name and my name is a god; I will not forget it, this name of mine.

I am Isis when she was in Chemmis, and I will listen like him who was deaf and who stared.

Go behind me for I am Isis!

These excerpts from the ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts show the technique precisely. Of course, those texts can often be a bit obscure. Here’s another example of the technique in a modern Neo-Pagan/Witchcraft/Wiccan context:

Cool moonlight streams into the Circle, falls upon the altar, glitters the silver jewelry upon the breast of the High Priestess. Her eyes are closed. Her arms and legs are flung wide—as if she would abandon her body by sheer human desire. She feels her heart radically alive. She breathes softly and deeply, praying in silence for the Goddess to come, to come.

Before her, the High Priest kneels, “I invoke Thee and call Thee, Mighty Mother of us all, By seed and root, by bud and stem, by leaf and flower and fruit, by life and love do I invoke Thee to descend upon this Thy servant and Priestess!”

The witches begin a low humming as the High Priest continues to invoke the Moon Goddess by Her many names, asking Her, praying Her to descend—now! now!—into the body of Her Priestess.

Then a sharp intake of breath. The High Priestess’ breathing has become ragged. Moonlight catches in her hair, illuminates her body. An electric thrill runs up her spine. The nape of her neck prickles with spirit fire. Her hair stands on end. Her dark eyes snap open, staring strangely. The atmosphere within the Circle is changed. Every one of us feels it. Excitement in the pit of the stomach. Anticipation. Truth.

The High Priestess looks into our eyes, into our hearts, and begins to speak the Charge of the Goddess, “Whenever you have need of anything, once in the month, and better it be when the moon is full, then shall you assemble in some secret place to adore the spirit of Me, Who am Queen of all the Witches…”

We have Drawn Down the Moon. The woman who was our High Priestess is—for this brief and sacred moment—the Goddess incarnate. And She gives us Her blessings.

Drawing Down the Moon

The name of the modern ritual practice of Drawing Down the Moon comes to us from ancient Greece, when it was a known practice of the famous Thessalian witches. The ritual was well known in even the highest intellectual circles of Greek and Roman society. Plato mentions it as do Lucan and Horace.

We have no evidence that the ancient practice was similar to the modern one. The scant clues we do have suggest that it was not. Nonetheless, the modern rite is not without ancient precedent. It is simply to be found somewhere else—in texts, some of which, are roughly contemporary with the height of the activities of the Thessalian witches: the Greco-Egyptian Magical Papyri. This collection of ancient magical workings is usually known as the Greek Magical Papyri (PGM) because they are written largely in Greek. Nonetheless, scholars are generally agreed that much of the magical technique to be found in them is Egyptian. (Yes, I’m finally getting to Egypt.)

As I said, we don’t have a sure Egyptian name for this powerful magical technique. I have called it Kheperu, “Transformations” or “Forms.” The Egyptian root of the word means “to be, to exist, to form, to create, to bring into being, to take the form of someone or something, and to transform oneself.”

Recognizing Kheperu

It’s relatively easy to tell when we are witnessing the technique of Kheperu. Most simply, whenever we find the deceased, the priestess, or the magician claim TO BE a particular Goddess or God and speaks in the first person, we are likely to be witnessing Kheperu. It is the voluntary taking on of the astral or imaginal form of a Deity that enables the ritualist to share, albeit briefly, in the powers and Divine energy of that Deity, usually for the purpose of enhancing the effectiveness of a ritual or for deep communion with that Deity.

A clear example comes from a Coffin Text about the Goddess Hathor. The deceased says:

I am in the retinue of Hathor, the most august of the Gods, and She gives me power over my foes who are in the Island of Fire. I have put on the cloak of the Great Lady, and I am the Great Lady. I am not inert, I am not destroyed, and nothing evil will come to pass against me.

The deceased “puts on the cloak”—the imaginal or astral form—of Hathor and becomes Hathor. Doing so enables him to use Her power to protect himself in the Land of the Dead.

The Egyptian Concept Behind Kheperu

There is a basic idea that must exist in a culture to make it possible for the idea of Kheperu to develop—and that is that human beings are not divorced from the Divine and that they have the ability to become even closer to the Divine.

And indeed, the idea that a human being could be god-like is found throughout Egyptian literature. In the Instruction for Merikare, wisdom literature from the First Intermediate Period, it is said that the deceased is “like a god” in the beyond and refers to humanity as the “likeness of God.” A human being with great knowledge is also said to be a likeness of God.

Deities are inherently godlike, but human beings who wish to partake of godlike powers have to make an extra effort—through ritual actions and by being in accord with Ma’et, “Rightness” or “Truth.” By proper words, deeds, and personal rightness, human beings may participate with the Divine.

Using Kheperu

The technique of Kheperu is a defining characteristic of Egyptian and Egyptian-derived magic. There are reasons to believe that it was more than a mere invocatory convention to the Egyptians and that a genuine connection with the Deity invoked was both intended and achieved. Kheperu was one of the key ways the ancient Egyptians empowered their spirituality—and it is one of the most important ways we can empower our own spirituality and our relationship with Isis, today.

Next time, we’ll look at some more background on this technique, then follow that up with some ways we can use it in our relationship with Isis and take our magic up a notch.