I rarely post anything political on this blog. That’s not what it’s for. But sometimes—like when your city has been invaded by goon squads kidnapping citizens—it’s hard to write about anything else. And so, for a lead-in to today’s post about ancient Egyptian sexuality and Isis, I am proud to introduce you to “Naked Athena.”

THIS. This is why I love this city. This is the power of a vulnerable, naked human body. This is the power of Art.

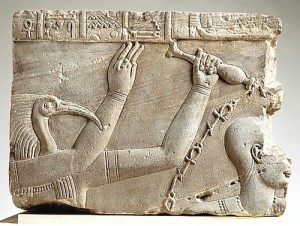

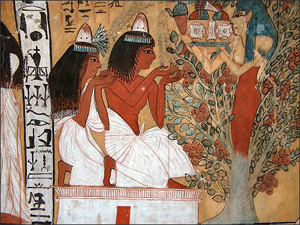

Now, here’s another photo of the same kind of vulnerable power:

What is the difference between the stories of these two photos taken four years apart? Naked Athena was not arrested for her protest (nudity is officially illegal in Portland, but court rulings have made exceptions for protests). Ieshia Evans was. It is blatantly obvious that there’s a lot of justice work to be done, folks. Ma’et calls us to it and Black Lives Matter.

Deep breath.

Of course, we do not always use our naked and vulnerable bodies for powerful protest. And so today I also bring you…

Sexuality, Sacred Sexuality & Isis, Part I

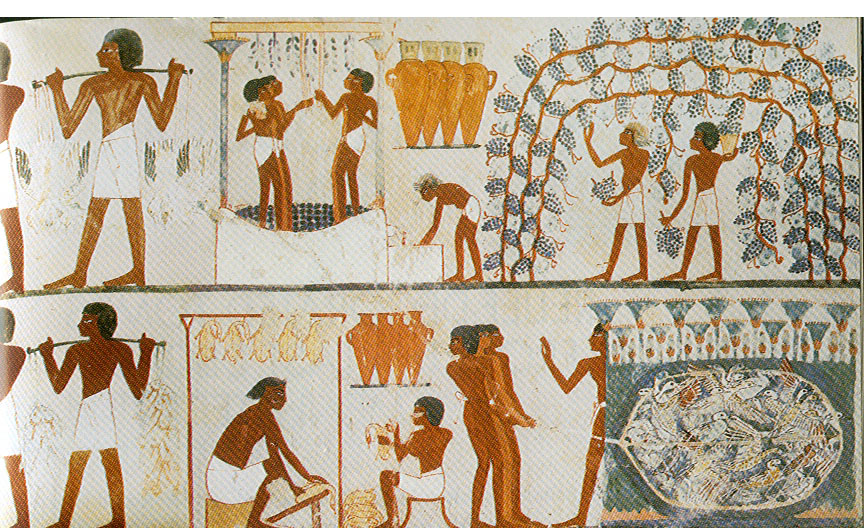

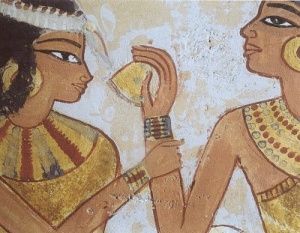

If you’ve ever looked into the topic of ancient Egyptian sexuality, you’ll know that they were pretty comfortable with sexuality. Sex was part of the great cycle of creation, life, death, and rebirth. You’ve no doubt read some of the famous ancient Egyptian love poetry with passionate lines like these:

“Your love has penetrated all within me, like honey plunged into water.” “To hear your voice is pomegranate wine to me—I draw life from hearing it.”

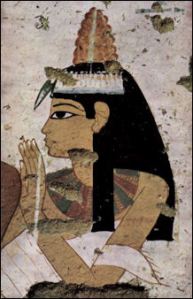

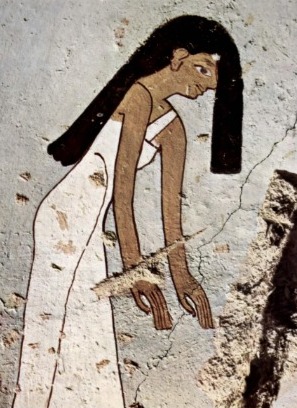

As well as some that are an appreciation of the sheer physical beauty of the beloved:

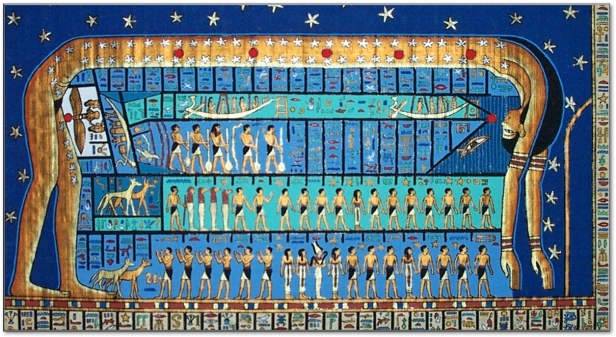

“Sister without rival, most beautiful of all, she looks like the star-goddess, rising at the start of the good New Year. Perfect and bright, shining skin, seductive in her eyes when she glances, sweet in her lips when she speaks, and never a word too many. Slender neck, shining body, her hair is true lapis, her arm gathers gold, her fingers are like lotus flowers, ample behind, tight waist, her thighs extend her beauty, shapely in stride when she steps on the earth.”

We have such poetic passion from the perspective of both the woman and the man. Before marriage, young men and women seem to have had freedom in their love affairs. After marriage, fidelity was expected, though it went much worse for the woman—including death—if she was caught in infidelity.

The ancient Egyptians present a puzzling picture when it comes to homosexuality. On one hand, we have copies of the negative confession in which the (male) deceased declares that he has not had sex with a boy. Because he had to declare it, can we assume that some men were having sex with boys? That I do not know. The only reference to lesbianism comes from a dream-interpretation book in which it is bad omen for a woman to dream of being with another woman. And most references to man-on-man sex refer to the rape to which a victor may subject the vanquished enemy.

And yet we have two instances of what seems to indicate a consensual homosexual relationship that seem to be okay: King Neferkare goes off with his general and it is implied that they do so for sex. We also have the tomb of what used to be called The Two Brothers. More modern researchers have suggested that the men, who were royal servants and confidents, were a gay couple. This is based on their tomb paintings, which show them embracing each other or in placements usually reserved for a husband and wife. The men are shown with their children, but their wives, the mothers of the children, are very de-emphasized, almost to the point of being erased. Some scholars say, yes, they probably were a gay couple, other say no.

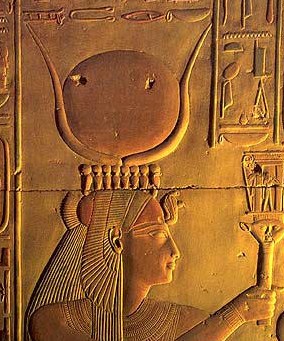

Yet I want to talk not about ancient Egyptian sexuality in general, but about sexuality and religion, and especially sexuality in relation to Isis.

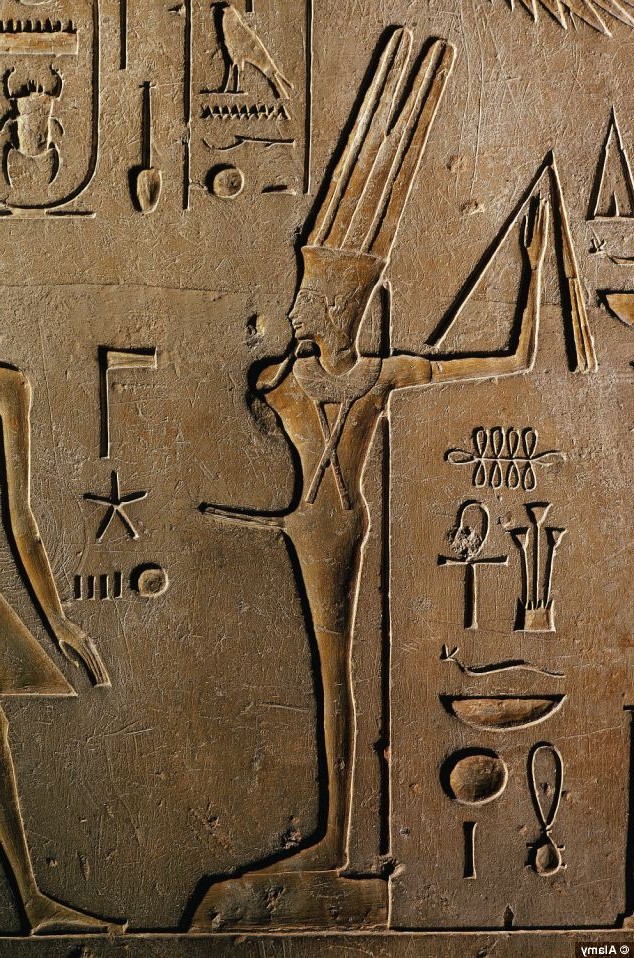

Temple Prostitution? Nope.

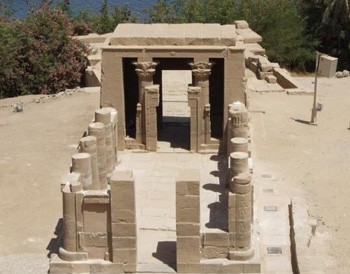

First, let us put the whole “temple prostitutes” thing right out of our heads when it comes to Egypt. There is no evidence of the practice in Egypt. Yes, I know. It was very exciting for the old gentlemen to contemplate the ever-so-Pagan goings on in those richly colored temples in days of old. But it may not have been quite how the old gentlemen envisioned it. (Please see my kindly rant on the old gentlemen of Egyptology here.) In fact, the one specific reference comes from the Greek geographer and historian Strabo (64 or 63 BCE-24 CE). Here’s the passage in its Loeb 1930s translation:

“…but to Zeus, whom they hold highest in honor, they dedicate a maiden of greatest beauty and most illustrious family (such maidens are called ‘pallades’ by the Greeks); and she prostitutes [or “concubines,” pallakeue] herself, and cohabits [or “has sex” synestin] with whatever men she wishes until the natural cleansing of her body takes place; and after her cleansing she is given in marriage to a man; but before she is married, after the time of her prostitution, a rite of mourning is celebrated for her.” (Strabo, Geographies, 17.1.46)

Well, it’s right there, ain’t it? But let’s take another look. The keys are the Greek word pallades that Strabo says the Greeks called such maidens, its relation to another Greek word, pallakê, and how it was translated, and the old gentlemen who did the original translating.

Pallades means simply “young women” or “maidens.” As in Pallas Athena. Virginity is often implied, but it doesn’t have to be. Pallakê originally meant the same thing; a maiden. However, pallakê had long been translated as “concubine” due to contextual evidence in some non-Egyptian texts. A highly influential scholar of near eastern and biblical texts, William Mitchell Ramsay—one of our old gentlemen, indeed—took the term to mean “sacred prostitute” and so-translated it when he first published these non-Egyptian texts in 1883. He based the translation on his own belief in ancient sacred prostitution and two Strabo passages: one about Black Sea sacred prostitutes and the one about the pallades we’re discussing. Ramsay was so influential that his definition became the reigning one. THE Greek-English dictionary, by Liddell and Scott, had “concubine for ritual purposes” as the first definition of pallakê. Now it is the second one.

A non-sexualized translation of the Strabo passage has been made by Stephanie Budin in Prostitutes and Courtesans in the Ancient World, edited by Christopher Farone and Laura McClure. Here it is:

“But for Zeus [Amun], whom they honor most, a most beautiful maiden of most illustrious family serves as priestess, [girls] whom the Greeks call ‘pallades’; and she serves as a handmaiden and accompanies whomever (or attends whatever) she wishes until the natural cleansing of her body; and after her cleansing she is given to a man (or husband); but before she is given, a rite of mourning is celebrated for her after the time of her handmaiden service.”

Sounds quite different, doesn’t it? Would it not be more likely that a highborn girl who has not yet had her period would serve as a handmaiden in the temple, attending whatever rites she wishes—perhaps even getting an education—until she proves herself marriageable by having her first period, rather than expecting an inexperienced girl to immediately start having sex with “whomever she wishes”? (And who would that be in the temple; the priests who were required to abstain from sex during their temple service?) Even the “rite of mourning” is explicable as a kind of farewell to childhood that the young woman would celebrate with her fellow handmaidens and priestesses as she left the temple to take up her married life.

What’s more, sex in an Egyptian temple was taboo. Even Herodotus knew of the prohibition against sex in Egyptian temples when he says that the Egyptians were the first to make it a matter of religion not to have sex in temples and to wash after having sex and before entering a temple. (Histories, 2.64)

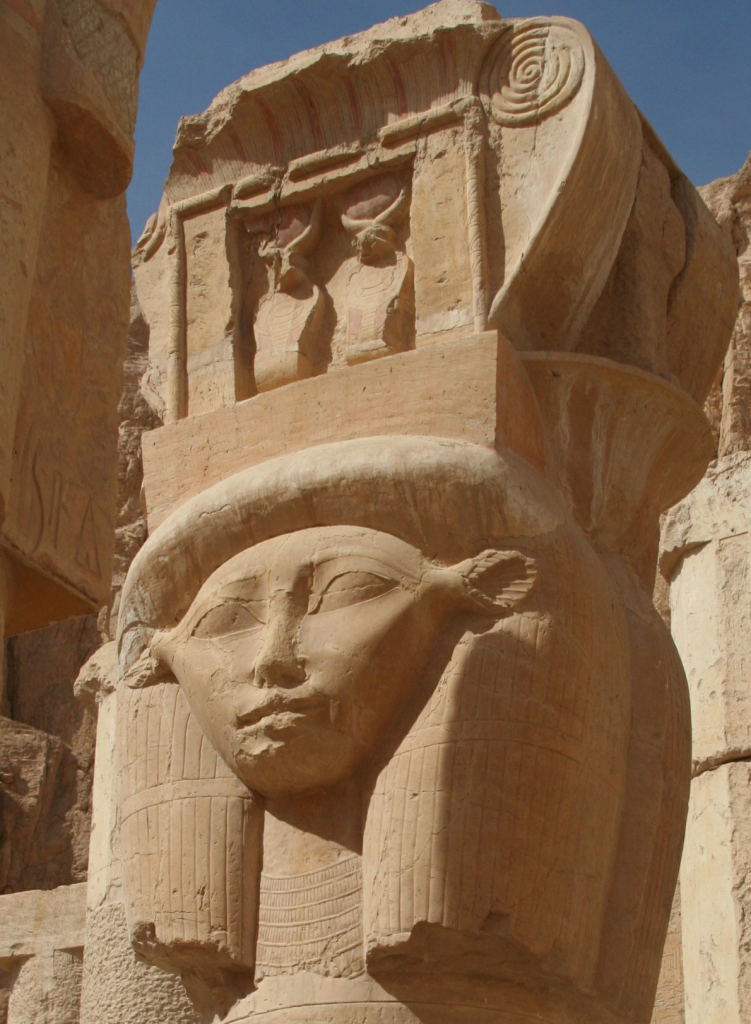

Alternatively, Budin wonders whether Strabo might have been hearing stories about the Divine Adoratrice or God’s Wife of Amun, powerful and high-ranking priestesses of the centuries before Strabo’s visit. But at least in the later dynasties, these priestesses were celibate and tended to rule long past their first menstrual period.

Sacred Sexuality? Yep.

Well. This post is long enough for today—and haven’t even gotten to Isis yet. So we’ll do that next time with more on sexuality in Egyptian religion…and we will indeed get to Isis.

As the days grow longer, a certain soft joy fills me.

As the days grow longer, a certain soft joy fills me.