This is one of the most popular posts on this blog. I don’t really have an update on this one, except to say that I still don’t have a snake. Though I know people who do, so I can get my snake fix.

We are repelled by them. We are fascinated by them.

Beautiful. Elegantly simple. One long muscle sheathed in glossy scales, some like brilliantly colored living jewels, some darkly and dangerously camouflaged.

There was a time when I really, really, really wanted a snake. I did my research. I discovered which kinds were likely to make the best “pets,” if I can even call them that, and how to care for them. Heck, both my Deities have serpentine connections; I should have a snake.

But in the end, I didn’t get a snake. We already had a fierce black cat and I figured the cat and the snake would pretty much drive each other crazy. Plus, I didn’t want to keep frozen baby mice in the freezer as snake food. Eeesh.

While I may occasionally see a little garter snake in my backyard (and if I come upon it unaware, it can still give me a tiny shiver), the ancient Egyptians came across serpents much more frequently.

No doubt that’s why serpents of all kinds played important roles in Egyptian mythology—as well as in Egyptian daily life. In myth, serpents were known to be both protective and harmful. In daily life, they were most often frightening due to the many extremely poisonous snakes that make Egypt their home. Two of the most important of these are the Egyptian Cobra, a big, aggressive serpent that can grow to more than two yards in length, and the now-rare Black-Necked Spitting Cobra that can spit blinding venom into its victim’s eyes at a range of more than three yards.

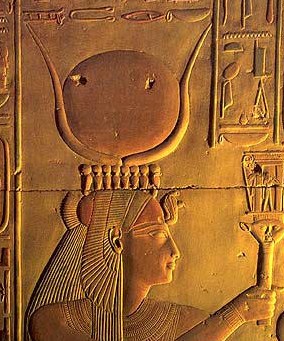

In ancient Egyptian art, the cobra is most often represented as the uraeus, the fiercely protective serpent seen guarding the foreheads of Deities, kings, and queens. As the uraeus, the cobra is a positive presence, a symbol of the power and protection of the Deities. Uraeus is a Latinized version of the Greek word ouriaos, which is itself a version of the Egyptian word uraiet, which indicates the rearing, coiled cobra. The root word has to do with rising up or ascending, so that uriet, a feminine word, can be interpreted as She Who Rears/Rises Up. The root word is also used to refer to the upward licking of flames. And indeed, the uraeus is often depicted spitting fire. This serpent fire represents both magical fire and the burning pain of the serpent’s venom.

In the Book of Amduat, an Otherworld guide, twelve cobras blast their fiery breaths to illuminate the paths of the Otherworld for the deceased. In other texts, huge cobras are seen spitting poison in the faces of enemies of the deceased. The uraeus cobras are usually Goddesses, which like the Hindu Shakti, are the active powers of the male Deity on Whose forehead They often sit. Uraei are also sent out as the Eye of the God; so to the cobra’s association with fire, we can add the symbolism of the powerful Divine Eye. With the Egyptian emphasis on transformation and renewal, the cobra’s ability to shed its skin and emerge renewed was symbolically important as well.

Although both Egyptian Goddesses and Gods wear cobras as part of their headdresses, mainly (but not exclusively) Goddesses have a cobra form. In fact, the cobra hieroglyph was often used as a determinative when writing the names of Goddesses or priestesses; and showing a cobra within a small enclosure could indicate the shrine of a Goddess. Cobra Goddesses are numerous in Egypt. The most prominent is Wadjet, the Green One. She is the tutelary Deity of Lower Egypt and one of the Two Ladies Who represent the Two Lands of Egypt. The Harvest Goddess, Renenutet, is a Cobra Goddess, as is Meretseger, She Who Loves Silence, the Goddess Who presided over the Theban necropolis.

As a fiery and protective Goddess, Isis also takes the form of a cobra. Sometimes She is the Eye of Re, the cobra-formed, solar power of the God. Sometimes She and Nephthys are shown as two cobras and replace Wadjet and Nekhebet as the Two Ladies of Egypt. Sometimes She is Isis-Thermuthis, a Hellenized form of Isis-Renenutet, the cobra harvest protector.

In Egyptian iconography, cobras are commonly found on Isis’ headdress, while in Greece and Italy, Isis could be shown holding a cobra, or with a cobra wrapped about Her arm. In the Graeco-Roman period, a cobra-formed Isis is paired with Her Graeco-Egyptian consort Serapis (and sometimes Osiris), also in a serpent form. As serpent Deities, Isis and Serapis are Agathe Tyche (Good Fortune) and Agathos Daimon (Good Spirit), and were considered the special protectors of Alexandria. Household serpents, called thermoutheis (pl.) from the name Isis-Thermuthis, were known to be the messengers of Isis.

Isis is also associated with the cobra in one of Her most famous myths. In the tale, Isis decides to gain power equal to Re’s. The Sun God is old and drools as He continues along His path in the sky. So the Goddess takes up some of His saliva, mixes it with Earth and forms from it a holy cobra which She places along Re’s path. The next day when Re passes by, the holy cobra bites Him. Re experiences pain like never before. He calls upon the Goddesses and Gods to help Him, including Isis. She reveals that She can cure Re if He tells Her His True Name, the most potent magical name in the universe. After much stalling, He eventually relents and tells Isis His Name. The Goddess heals Re and renews Him so that He can continue on His path through the heavens; meanwhile She gains power for Herself—through the magic of a holy cobra. (Please see my discussion of this important myth in Isis Magic and here.)

Have you ever handled a serpent, felt it coil about your wrists or up your arms, exploring with its flicking tongue? If you have, you have touched the beauty of Isis in one of Her most compelling and awe-striking forms.