What does it mean to serve the Goddess Isis?

With a number of us gearing up to serve as ritualists in an upcoming Pacific Northwest Fall Equinox Festival, I’m re-running an older post on what it means to serve Isis as Her priest/ess. (Also, I’m scrambling to get the ritual written before our next Festival Crewe gathering, so bear with me.)

Of course, not all of our Festival ritualists will desire a relationship with Isis beyond the festival. Probably most won’t; they may already have important Divine connections in their lives. But for those who may, I offer these next few posts as starting thoughts for discovering a specific type of relationship with Her.

Oh, and another thing. As these are older posts, they used the gendered terms “priestess” and “priest.” As a community, we haven’t yet settled on a gender non-specific title for the intensely connected relationship with the Goddess that I will be talking about. So I’m going to try out a new one…and we’ll just see how that goes.

In ancient Egypt, the terms were very gendered; you really can’t get around that. One was either a Male Servant (hem) of the Goddess or one was a Female Servant (hemet) of the Goddess. So we’re not going to rely on ancient Egyptian terms, but English.

And now, here’s the older post with updates…

Of course, we can all have a deeply meaningful personal relationship with the Deity or Deities of our choice in whatever capacity we choose. But being a ministrant of the Deity is a particular kind of relationship; a particularly worthwhile one if you find yourself attracted to Isis.

If you already serve a specific Deity, you have likely already done some thinking on this topic. If not yet, you may decide, sometime in the future, that you’d like to have a deeper, more formal relationship with Isis as Her ministrant.

But what does it mean to serve Isis in this way? The easy answer is that it means different things to different people. The more difficult, and truer, answer is that we each have to figure out for ourselves what it means to us.

So how do we do that?

A good place to start is with what it has meant to serve the Goddess in this intensely connected manner. So over the next few posts, we’ll talk about some of the things we know about ancient Servants of Isis as well as some of the ways we can discover for ourselves what being Her ministrant may mean to us today.

Serving the Goddess

Service has been part of a ministrant’s job description as far back as we know. In one sense “one who serves” is the very definition of this role. This is true of our English word “minister.” To minister is to serve and, as you can see, it is the basis of the non-gender-specific word I’m trying out here. Generally, a ministrant’s service goes two ways: to the Divine and to the greater circle of worshippers.

For people in mainstream religions, which have very prescribed ways to serve, things are—in at least this way—easier. For example, if you are a Catholic priest (you can’t be a Catholic priestess), you would have a very clear idea of what it meant in your particular religion to “serve God.” You would have gone through specific training meant to teach you precisely this.

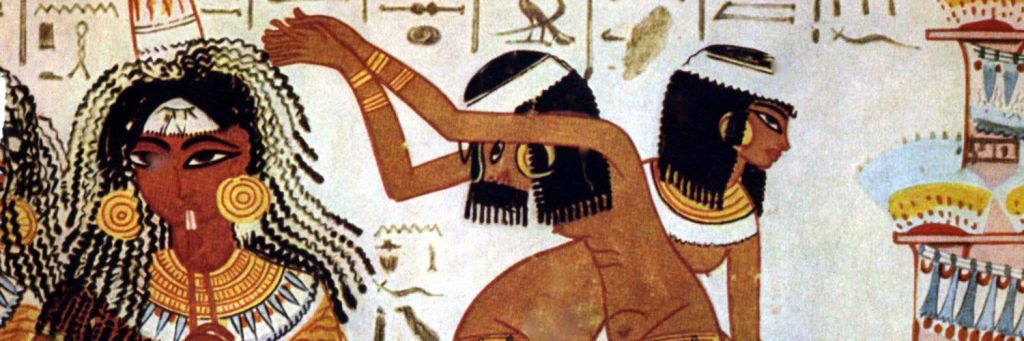

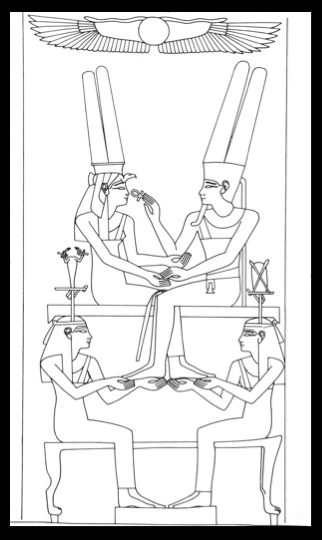

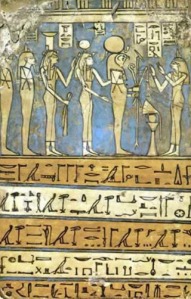

Having precise ways to serve was true in ancient temples of Isis, too. Besides the upkeep and maintenance of the temple complex, there were particular ritual acts that had to be performed every day; for example, opening the shrine of the sacred image of Isis each morning and “putting Her to bed” each night. And of course, there were offerings to be made, festivals to be celebrated, and funerals to conduct. A ministrant of Isis might play the role of the Goddess in certain rituals. The Servants of Isis would learn the words to the sacred songs and invocations and how to perform them properly in the rites. Some served as sacred musicians.

But this type of formal structure of service is not available to us today. In a non-mainstream, more informal type of spirituality—such as those of the modern Pagan-Polytheist-Wiccan-Witch-insert-your-identifier-of-choice-here communities—things are less clear. It means that this path, if truly and deeply followed, is more difficult than those of mainstream religions because we have to blaze our own trail. It also requires a significant degree of perseverance and self-honesty to be able to make the important decisions that we must make when creating a personal path.

To take this alternative path, we need perseverance because we will not always know which branch of the path to take…or it will be dark…or it will even be boring. We need self-honesty because we often walk this path alone. And walking alone, with no one to consult, we can sometimes take a wrong turn. We can delude ourselves into not seeing things about ourselves or a situation that we should be seeing.

On the other hand, this path can be extremely rewarding precisely because it is difficult. Whereas in mainstream religions there tend to be established answers to the Great Questions, we must find our own answers—fresh and new every time. What happens after death? What does it mean to serve Isis? Why is there evil in the world? What is the nature of reality? What is the nature of humanity? What is the nature of the Divine?

All these are important questions that spiritual people have tried to answer from the beginning of time, and for which we still seek answers today. It is worth our time, as lovers of Isis, to seek our own answers to these questions.

Some will define service as “doing Goddess’ will on earth.” That’s a valuable insight; but how do you know if you’re doing Her will? Is it as simple as listening to your inner voice? Perhaps. Yet how do you know you’re hearing correctly and not coloring it with your own personal psychology or desires? I can tell you for a fact, it will ALWAYS be colored by your own personal psychology and desires. That’s not a disaster; it just brings us back to that self-honesty thing.

So how do you get around yourself? Discovering how to do that is part of the work of a ministrant of Isis. For some, it may be the key part. So I’m going to come back and talk about this some more when I come to the topic of personal spiritual development in a later post. For now, back to service.

What about the other kind of service—service to the greater circle of worshipers?

You’ll find a wide variety of expressions of service in this area. Some ministrants are always available to help those in their circle, whether with spiritual or personal problems. Some take the responsibility of organizing a circle and keeping it running as their service, but don’t expect to be called on the solve personal problems. Some represent their tradition to the greater Pagan community by organizing large festivals. Some organize or moderate blog communities. Some teach. Some don’t.

Again, it is a personal decision as to how you might decide to serve. Yet I do think that we are obligated to do some service of this type. By serving other people in these ways, we acknowledge the importance—the value—of other people. By serving people, we integrate this knowledge in a deep, intimate, and personal way. (I hear some of you moaning right now. People are SO difficult. Yes. Yes, they are. And complicated. You bet they are. But they are also very worth your time and care. So very, very worth it.)

The same is true of service to others who are not a part of your circle; humanity as a whole. Many religions—most religions, actually—place value on helping those in need. Feeding the hungry. Clothing the cold. Sheltering those without shelter. This sort of service is appropriate for the ministrant of Isis as well. Caring in this way makes us aware of other people and their needs and problems. It encourages our compassion and discourages our ego-centered-ness. At the very least a Servant of Isis should give money to charity—anonymously, if possible. Do other good deeds. Help people. Help the earth. And be aware of doing whatever it is you are doing in the spirit of service—with an open, compassionate heart. In this, we do our best to imitate the compassion of Isis Herself when She healed the child of the woman who refused Her shelter or withdrew the spear from Set even as He threatened Her own son, Horus.

Ultimately, serving others makes this world a better place one person at a time. Spread kindness and you will serve Isis.

Live Your Life Mission (Free Workshop)

Live Your Life Mission (Free Workshop)

Offering to Isis: Fall EQ 2021

Yes!

The Pacific Northwest is ON for an Isis-themed Fall Equinox Festival (Sept. 24-26, 2021). This is not the same festival we were planning for 2020. That one was much more…involved…shall we say. This one is a gentle way of coming together once again as a community. So I’d like to share with you the write up for the festival, then I’ll repost something on Making Offering in the Egyptian way that will be related…

Offering to Isis: A Fall Equinox Celebration of the Goddess and of Community

If you asked the ancient Egyptians, the act of Making Offering was one of the things that maintained Ma’et, that which is Right and True. Offering helped keep the world in balance. Making Offering is part of the great reciprocal flow between the Divine and the human. It is one of the most important ways we communicate with our Goddesses and Gods. It is hallowed by tradition. It is empowered by magic.

As we turn the wheel at this Fall Equinox, let us come together in rituals of offering. Under the Wings of the Great Goddess Isis, let us gather in a celebration of our reentry into and reconnection with Community. In the presence of Isis Myrionymos, Myriad-Named Isis, Goddess of the Ten Thousand Names, let us gather with open hearts and generous spirits to Make Offering.

As we human beings have always done—from the First Time, the Zep Tepi—we shall give gifts to Isis and we shall receive gifts from Her.

We are living through extraordinary times. Many of us have gone through intense changes. There have been painful losses. And there have been surprising gains. Through Rites of Offering, we can give thanks, mourn losses, and ask for aid. We can find Divine connection and reawaken our hearts.

The Rites of Offering

Our rituals are inspired by the Daily Offering Rites worked in ancient Egyptian temples. We will come together four times, at the cross-quarters of the Holy Day and Sacred Night, to Make Offering to the Goddess in four of Her myriad names.

Yet, as a Community, we are many different people, on many different paths, who honor many different Deities. And so the Iset Weret— the Great Throne Altar of Isis—will welcome all our Divine Ones. If you wish, you are invited to bring an image or symbol of your own Divine One/s to add to the Great Altar that They may receive Offering as well.

Now, Let’s Celebrate

This festival is intended to give us plenty of open time so that we can be together…for feasting, drumming, dancing, and just relaxing. No formal workshops are planned.

Come join us in this Fall Equinox celebration as, under the Wings of Isis, we come together as a Community once more.

Now here’s a little something about Making Offering…

****************************************

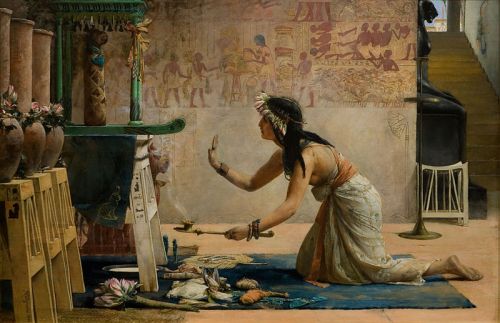

Can Isis smell the flowers we place upon Her altar? Does She eat the delicacies we so carefully arrange upon Her offering mat? Does She drink the wine we pour into a beautiful cup and lift to the smiling lips of our sacred image?

Well, no.

And, yes.

Although I have had weird phenomena happen with offerings—for instance, once an entire two-ounce packet of incense (you DO know how much two ounces of powdered incense is, right?) was apparently incinerated without leaving a whiff of scent in the air of our tiny temple space—usually, the flowers wither naturally, the food dries to inedibility, and the wine evaporates.

So did the Goddess receive Her offerings or not?

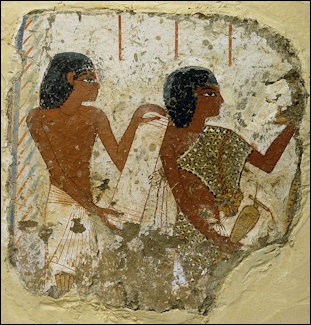

For the ancient Egyptians, the sacred images of the Deities were sacred precisely because they were filled with some measure of the Deity Her- or Himself. Offerings to Isis were received by this bit of the Goddess residing in the image, and through it to Her greater Being.

The main spiritual mechanism for the transfer of an offering from offerent to Deity was the ka, or vital, life energy. All living beings—Deities, human beings, animals, fish, plants, stars, mountains, temples—have a ka. The kas of the Goddesses and Gods are extremely powerful. In one Egyptian creation myth, the Creator Atum embraces His children, the God Shu and the Goddess Tefnut, with His ka in order to protect Them from the primordial chaos of the Nun into which They were born—and, importantly, to transfer His ka to Them, giving Them life. Ka energy exists before a being comes to birth, is joined to that being at birth, lives with them throughout life, then travels to the Otherworld after death. The tomb became known as the Place of the Ka (among many other designations) and to die was to “go to one’s ka.”

The ka “doubles” the person physically, yet the ka is not essentially personal. It is held in common with all living things—including the Deities. The ka was the ancient Egyptian’s connection to a vast pool of vitality greater than the individual person.

But that’s not the end of it. One meets one’s ka after death where it can continue to protect.

Utterance 25 of the Pyramid Texts says that the dead king “goes with his ka.” Just as a list of Deities “go with Their kas,” so does the king:

“You yourself also go with your ka.

O Unas, the arm of your ka is before you.

O Unas, the arm of your ka is behind you.

O Unas, the leg of your ka is before you.

O Unas, the leg of your ka is behind you.”

You might recognize this formulation. It is a common magical formula for invoking protection on all sides; similar to casting a circle or the Lesser Banishing Ritual of the Pentagram or part of the so-called Breastplate of St. Patrick (“Christ at my right. Christ at my left, etc.”)

Even though ancient Egyptians could experience the ka as separate from themselves, the ka also connected the person with the long line of humanity—for the ka was associated with the ancestors. In fact, the ancestors were thought to be the keepers of ka energy. Jeremy Nadler suggests that when people died, the Egyptians believed that they returned to the ka-group of ancestral energy to which each person naturally belonged. In other words, after death, the ka returns to its family.

This meant the living had several reasons for making offering to their ancestral dead. As we all do, they wanted to remember loved ones who had died. The offerings provided their ancestors’ kas with the nourishment required to keep the family spirit strong. But since the ancestors had ready access to the greater pool of beneficial ka energy and could bestow it on the living, people could also ask their ancestors to send them a blessing. A blessing of ka energy could nourish human beings, animals, and crops alike.

As usual in Egyptian society, the king was a special case. He could have multiple kas. He also had more intimate contact with the powerful ka energy of his royal ancestors than the average person had with their familial kas. The royal ka was especially connected with the power of the God Horus. By the time of the New Kingdom, the king’s ka was specifically identified as Harsiese, “Horus, son of Isis.”

In Egyptian, the word ka is related to numerous words that share its root. Egyptian words for thought, speech, copulation, vagina, testicles, to be pregnant and to impregnate, as well as the Egyptian word for magic (heka), all share the ka root. And all have some bearing on the meaning of ka. Ka is also specifically the word for “bull” and “food.” Connections such as these reveal mysteries. Ka is also the bull because it is a potent, fertile energy that contains the ancestral seeds that connect us with our families. Ka is also food for it is the energy that nourishes life, in both the physical and the spiritual realms. Ka is intimately connected with offering; the plural of ka, kau, was used to mean “food offerings.” Sometimes the ka hieroglyph replaces the images of food inscribed on offering tables.

Kau, food offerings, provide life-energy for the individual ka. When the Egyptians offered food to their Deities or honored dead, they were offering the ka energy of the food to the ka of the Deities or ancestors. The ka inherent in the kau nourished the ka of the spirit being. Offering thus feeds the kas of the Deities and ancestors and the great pool of ka energy to which all enlivened things are connected. Simultaneously, the great pool of ka energy is the source of the energy found in the offerings by virtue of the ongoing, archetypal connection with it. By making and receiving offering, a great reciprocal power system was set up and could be eternally maintained. No energy was ever lost; it was continually transformed and re-activated by being offered and received, received and offered. Ka energy may be considered the food that fuels the engine of the living universe.

Since offerings are given and received ka to ka, it is no wonder that the Egyptians who made offering before the sacred images in the temples, did not expect the Deity to physically consume the food or drink offered. Instead, they expected the Deity’s ka, residing within the image, to take in the energy from the kas of the offerings. Ancient texts are explicit about this. A text from Abydos says that the pure, Divine offerings are given daily “to the kas” of the temple Deities. Sometimes the Deities are said to have been “united” with Their offerings. It is the ka of the offering and the ka of the Deity that unite. In another text from Abydos, the king asks the Deity to bring His magic, soul, power, and honor to the offering meal. Clearly, the king is not expecting a physical appearance, but a spiritual one.

It is the same with our offerings. We offer the ka of the kau to Isis and Her ka receives it. We can open our awareness to this aspect of offering by envisioning the ka, perhaps as Light, move from the offering to our sacred image of Isis (if we are using one) or to an image of Her we hold in our mind’s eye. In this way, we can know that Isis has indeed received what we offer to Her.

Isis the Ass-Kicker

A little while ago, I had the opportunity to be in the same room with several other priestesses of Isis and we were talking about Her (as priestesses of Isis are wont to do).

All of us agreed with this statement: “Isis will kick your ass.” And each of us knew exactly what the others meant by that.

We had all experienced it, you see.

But just in case you haven’t yet had the opportunity to have your own sweet butt kicked by the Goddess, I’ll explain.

When you undertake a relationship with Isis, whether that be as a priestess, priest, or devotee, it is more than likely that She will ask something of you. For instance, She might want you to get your physical surroundings in order so that you can create a temple space for yourself. She might want you to quit smoking. She might want you to start a group to teach Her Mysteries. She might want you to create a ritual or a work of art. She might ask you to volunteer at a homeless center. She might insist you learn something particular—or finally see a doctor about that issue you’ve been having.

In my case, She wanted me to write for Her.

Now, I say, “She might want,” but what I really mean is, “She will demand.” Not in a whiny, naggy way, but in an insistent, just-keep-bringing-it-up-to-you way. Like a good mother teaching Her child, the Goddess makes sure that Her request just kinda seems to be in your face all the time…until you do it, or at least until you get started on it.

But that’s just the surface stuff.

The real ass kicking is what happens as you actually undertake your mission from the Goddess.

You grow—and growth can sometimes be painful. What Isis asks you to do usually has some value in terms of your earthly life (a cleaner house, cleaner lungs), but the secret is that this particular task has also been chosen by Her to help you grow spiritually. This means that it will usually bring up some soul issues (psychology is the study of the soul; you knew that, right?) that you need to deal with in order to be a competent priestess, priest, or devotee.

And while you’re trying to deal with those little tender spots in your psyche, She will also demand of you complete honesty. Honesty with yourself. You must accept your part in your own problems; and you must accept your greater part in the solution. There’s no hiding, no blaming other people, no whining. (Well, you might whine a little and, in that case, She will always, always comfort you.) This combination of Divine persistence and motherly comfort and kindness creates the space for each of us to truly grow in Her presence.

Personally, I’ve never been sorry when She kicked my ass. I think the priestesses with whom I spoke the other night would agree. How about you?

“Doing Things” for Isis

Those of you who have been following this blog for a while may be familiar with my small rants about The Old Gentlemen of Egyptology and their innate sexist attitudes. Well, today it’s time for another rant…just a little one…but this time it’s about the Even Older Gentlemen of Ancient Egypt and their innate sexist attitudes.

You see, I just came across a scholarly article by Carolyn Routledge entitled “Did Women ‘Do Things’ in Ancient Egypt? (c. 2600-1050 BCE)” at the same time as Academia.edu served me up a thesis by the same Carolyn Routledge about ancient Egyptian ritual practice, which was an in-depth study of two specific words having to do with ritual, one of which translates as “doing things” (iri ḫt).

Routledge explains that the Egyptians used ir ḫt (“to do things”) in several specific ways. In addition to its meaning as ritual performance, including funerary rites, it also has to do with the performance of work or duty, and even negative behavior. It was used particularly in relation to physical activity.

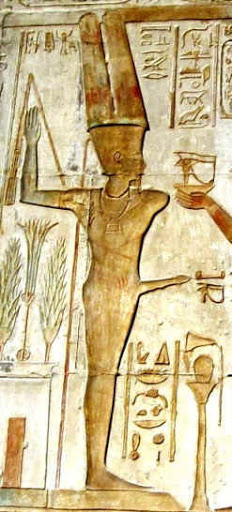

Of course I’m most interested in ir ḫt meaning “to do ritual.” The kinds of ritual activities that were Done included libating and censing and making offering: “you perform rites [iri ḫt]; bread, beer, and incense upon the flame.”

Interestingly, there also seems to be some emphasis on doing these things with one’s arms and hands. Makes me wonder whether, in addition to the sheer physicality of using a sacred vessel to libate, a censer to burn incense, or employing some other ritual object, there was also supposed to have been an accompanying gesture. There also seems to have been a connection to written instructions in the performance of ritual. So the lector priest, the sacred reader, was one who definitely Did Things.

If one wanted to be quite specific, one could also say he was iri ḫt nṯr, “doing God’s rites” or iri ḫt nṯrt, “doing Goddess’ rites.” But notice that pronoun I just used in relation to the person doing the Doing? Yeah. He. Sadly, Routledge answers the question posed in her article title with a resounding no; women did not Do Things. At least as far as we can tell from the evidence left to us, and I must admit it seems reasonably conclusive.

For example, the king has the title, neb ir ḫt, “Lord of Doing Things.” It is often used in connection with the king Doing Things that maintain Ma’et, including cultic functions as well as kingly duties and activities. The queen, however, does not Do Things. She has no title, Lady of Doing Things. Instead, she “says all things and it is done for her.” I used to think that was a nice expression of queenly power; now, I’m kinda thinking it’s the opposite: an expression of the perceived inability of women to Do Things themselves.

There are only two exceptions: Sobeknefru and Hatshepsut, both women who ruled as king, not queen. In Hatshepsut’s case, about half of the references to that title are in the masculine form, half in a feminized form: nebet ir ḫt. (We have no references to Tausert, a later woman ruler, having that title.)

The exclusion of women from Doing Things is, of course, the basis of my rant. Or maybe it’s not even really a rant. More of a whine. Or an exhausted, put-upon sigh.

The king, priests, and officials of all stripes Did Things. But when it came to women, the “things” part of the important phrase was avoided. There are instances of women iri irw, “doing doings” or “performing performances,” but not iri ḫt. Routledge gives an interesting example of a husband and wife, both named Djehutynakht, both with the same funerary text on their coffins, but hers excludes the word ḫt.

It’s practically impossible not to smell the old sexist weakness-of-women, unfitness-of-women-for-important-stuff stereotypes here. But we don’t know. Routledge suggests that it may be because iri ḫt was associated with educated, literate, and highly trained people, very few of whom would have been women in ancient Egypt. True enough. But the question underlying that conclusion is “why not?” Which, of course, refers us back to the first sentence in this paragraph.

So what can we do with this information? Why am I sharing it with you?

First, I enjoyed learning an important ancient term for doing ritual and reading about its specific connotations. Second, we sometimes tend to idealize the ancient Egyptians—we do so love their Deities, their art, their magic and mysterious ancient wisdom. It is important to know that every society—theirs, ours, everybody’s—has flaws, often significant ones, and we should not be blind to them. And in our own case today, we must work to fix them.

And third? Third, I hope to encourage all of us to Do Things for Isis. We all have the capacity for Doing Things in the ancient sense: with power, purpose, and effectiveness. Let us also be reminded that the physicality of ritual is important. For when we are fully engaged with what we are Doing—body, mind, soul, and spirit—ritual is far from being empty show. It is instead Right Action that can truly Open the Ways so that we may come, once more, to the Divine Heart of Isis.

Rose of the World

The Rose of the World festival, Rosa Mundi, begins the Fire and Rose season.

It is a time when the veil between the worlds is thin and magic is all around.

This festival is especially associated with the soul's quest for union with the Spirit our Mother.

Read more about Rosa Mundi

The Rose of the World festival, Rosa Mundi, begins the Fire and Rose season.

It is a time when the veil between the worlds is thin and magic is all around.

This festival is especially associated with the soul's quest for union with the Spirit our Mother.

Read more about Rosa Mundi Rose of the World

The Rose of the World festival, Rosa Mundi, begins the Fire and Rose season.

It is a time when the veil between the worlds is thin and magic is all around.

This festival is especially associated with the soul's quest for union with the Spirit our Mother.

Read more about Rosa Mundi

The Rose of the World festival, Rosa Mundi, begins the Fire and Rose season.

It is a time when the veil between the worlds is thin and magic is all around.

This festival is especially associated with the soul's quest for union with the Spirit our Mother.

Read more about Rosa Mundi Becoming Joined to Your Star

Perhaps it was coincidence or perhaps it was the hand of Isis, but twice in the past week, the idea of “being joined to one’s star” has been brought sharply to my attention. So today, let’s talk a bit of the Way of the Stars…and especially the way of our own personal star.

In Isis Magic, the Path of the Stars is the path of the Prophetess or Prophet of Isis. (In Egyptian, this would be Hem/et Nutjeret; the Servant of the Goddess.)

On this path, we deal with the important star Sirius (Sothis in Greek, Sopdet in Egyptian), which is the Star of Isis. The Goddess Herself may be seen in the star and sometimes the star is said to be the ba, the manifestation or soul, of the Goddess

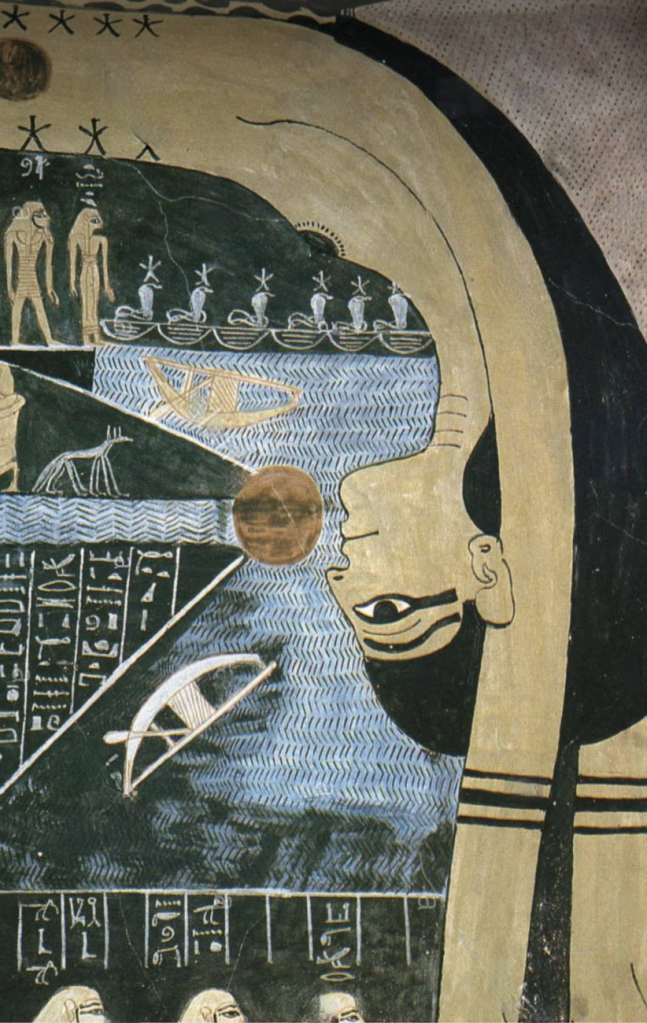

We honor Isis in Her singular and beautiful star, but on the Path of Stars, we also work with the idea of a universe filled with millions and millions of stars—stars that are, like us, within the body of Nuet, the Sky Goddess and Mother of Isis.

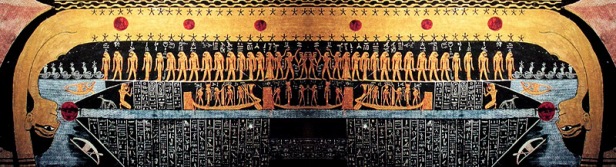

In the Pyramid Texts, it is clear that the deceased king ascends to the heavens and becomes a star. This ascension also makes him Divine, a god among Gods. He takes his place in the otherworld as a star, sometimes called the Lone Star or the Morning Star.

In Utterance 245 of the Pyramid Texts, the Sky Goddess says to the deceased, “Open up your place in the sky among the stars of the sky, for you are the Lone Star, the companion of Hu…” (Hu is one of the great creative powers of Re, “Creative Utterance.” It may be that the Goddess is likening the king to Sia, “Perception,” for indeed he specifically declares himself to be Sia in Utterance 250.) Utterance 248 reiterates the king’s star-nature. He is “a star brilliant and far traveling,” and he has “come to his throne which is upon the Two Ladies [Isis and Nephthys or Wadjet and Nekhbet] and the king appears as a star.” A text from the tomb of Basa, a priest of Min and mayor of ancient Thebes, says of the deceased, “your star be in heaven, your ba upon the earth.”

While the Pyramid Texts are concerned with the king, as time went on, the Egyptian conception of the otherworld got more democratic; everyone could participate and have their own Divine stars.

But if you’ve read any of the Pyramid or Coffin Texts or the Book of the Dead, you’ll know that those sacred texts are not intended just for the dead. The texts tell us that the knowledge they impart is also beneficial for living human beings. “As for him who knows this spell on earth . . . he will proceed to a very happy old age” says one text. Another states that anyone who knows the spell will “complete 110 years of life,” while yet another explains, “it is beneficial for anyone who does it.”

The same thing applies to being conscious of or joined to your star. It is not solely a post mortum activity. If our “star” is our Divine Self, the one we will hopefully become after death, then to know our star in this life means that its light can serve as a guide as we move through our current earthly lives. What would my star self do in any given situation?

One of the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri even has a specific ritual for learning about “your star,” and which is referred to as “an initiation.” There are quite a number of preparations, but in short, you purify yourself for seven days while the moon is waning. On the night of the dark moon, you begin sleeping on the ground each night for seven nights, waking every morning to greet the sun and to name the Deities of the hours of the day. On the eighth night, you rise in the middle of the night, perform a series of invocations and magical acts, recite the account of creation, and call upon the Great God. When the God arrives, you avoid looking in His face and ask Him about your fate. “He will tell you even about your star and what kind of daimon [spirit] you have…” (PGM XIII 646-734)

It is well for us to know “even about our star.” For it illuminates the individual life and spiritual path that is uniquely ours, but it also places us in the company of the Divine Ones.

I did a meditation, not too long ago, about the Child Horus in the stillness of the womb of Isis. It came to me that it may be there and then that we are first joined to our stars. But to truly benefit from this starry relationship throughout our lives, we must continually renew, strengthen, and deepen the connection so that our star’s holy light may always inspire and guide us.

We might think of our star as our Star Self or Isis Self. But, like the Goddess Herself, it has many other names as well. It can be called the Higher Self, the Augoeides (“Shining One”), the Holy Guardian Angel, the Higher and Divine Genius, Christ Consciousness, the Atman, the True Self, the Inner Teacher, and many more. And when we are joined to it, we will be our truer and more divine selves.

Living Your Life Purpose Today: 4 Quick Steps (Free Workshop)

Living Your Life Purpose Today: 4 Quick Steps (Free Workshop)

Isis the Scorpion

A friend living in the desert told me she’d been stung by a scorpion and that, in her words, “it royally sucked.” No doubt. The ancient Egyptians, as you may know, had the same problem…and often with much more poisonous scorpions than the one that got my friend.

Since much of Egypt is dry desert, it has plenty of scorpions to go around. It’s true today just as it was in ancient times. In fact, the danger of scorpion sting was ever-present; and because scorpions are smaller and harder to spot, the chance of getting stung by a scorpion outweighed that of snakebite.

Whether an Egyptian’s experience of scorpion sting merely royally sucked or took them to the afterlife depended on which scorpion did the stinging as well as the size and health of the victim. For instance, one of the most poisonous scorpions in the world, the Palestine Yellow—aka The Deathstalker—is found in Egypt today. Luckily, it is small and cannot deliver enough poison to kill an adult, though that has happened.

On the other hand, scorpions were a lethal threat to children, as well as to pets, especially cats. Picture a scorpion with its scuttling movement and raised and waving tail and you’ve pretty much got an irresistible cat toy.

Not surprisingly, we have a number of ancient Egyptian healing spells against scorpion sting, including this heart-rending one for a pet cat:

O Re, come to Your daughter for a scorpion has stung her on a lonely road! Her cries have reached heaven. Come to Your daughter! The poison has entered her body and it has spread in her flesh. She has put her mouth to the ground, See, the poison has entered her body! Do come with Your power, and Your rage, with your wrath! See, it is concealed from You, now that it has entered the whole body of this cat under my fingers…”

The rest of the formula has Re come to save His daughter, the cat, by identifying the various parts of her body with the Deities. (This is the same formula that was often used for human beings, by the way.) At the end of the formula, Isis and Nephthys join in the healing and weave Their protection: “Isis has spun and Nephthys has woven against the poison.”

Yes, of course, we have to circle around to Isis, for Isis is a formidable Scorpion Goddess Herself. In this guise, She is called Iset Ta-Wahaet, Isis the Scorpion. In other texts, Isis is joined with Serket Hetyt, the Scorpion Goddess, “She Who Causes the Throat to Breathe,” as Isis-Serket. (It is interesting to note that, since scorpion venom is a neurotoxin, death from a scorpion sting is by asphyxiation, that is, suffocating.)

At Isis’ sanctuary at Koptos, it was said that during the time when the women ritually lamented with the Goddess, they could walk through a mass of scorpions unharmed. Late legend had it that scorpions would refuse to sting any woman—or any worshipper of Isis, for that matter—out of respect for the Goddess.

Scorpions are the faithful companions, protectors, and guides of Isis in one of Her most famous myths.

In the tale, Isis is fleeing in an attempt to hide Her newborn child, Horus, from Set. Seven magical scorpions accompany her. In what smacks of a ritual formula, we are told that the scorpions Tefen and Befen walked behind Isis. On Her right was Mestet, on Her left, Mestetef. Before Her walk Petet, Thetet and Maatet.

Upon reaching a city at the edge of the papyrus swamps, Isis found She was weary and approached the home of the chief woman of the district for shelter. But seeing the scorpions, the woman was afraid and angry that anyone would dare approach her home with these dangerous creatures. She refused the Goddess. The scorpions became angry at the rejection and vowed revenge. While Isis found refuge with a poor woman, the scorpions gathered all their poison together and placed it in the tail of Tefen. Tefen entered the home of the chief woman and stung her young son who fell instantly from the terrible poison. But Isis took pity on the child and cured him. At this, the chief woman was ashamed of her behavior and filled the home of the poor woman who had sheltered the Goddess with beautiful gifts from her very own home.

This story about the seven scorpions and Isis is, in fact, from a healing spell to cure a scorpion sting. In another tale—also from a healing formula—the son of Isis, Horus the Child, is stung by Set in the form of a scorpion. Isis stops the Boat of the Sun in the sky so that Thoth can come down and cure the child. (It may seem odd that Isis Herself could not cure Horus, since it is She Who is called upon in other scorpion spells to do the healing—but that’s the story and I’m sticking to it. Perhaps additional magic was needed because this was no ordinary scorpion, but Set in disguise.)

Right after this story is another spell for healing a scorpion sting using seven magical knots (perhaps alluding to the seven Isiac scorpions?), and following that another one in which Isis invokes Re to heal a scorpion-stung Horus. Parts of that formula sound very much like the language used in the story of “Isis and Re” in which Isis cures Re of snakebite. There are also formulae in which Horus is the one Who cures the scorpion sting. There are yet others that are spoken to stop the scorpion from coming near by blocking or enwrapping it. I love this line from one of those spells:

A very small thing, a sister of the snake is the scorpion, a sister of Apophis [the great Enemy Serpent], sitting at a crossroads, lying in wait for someone who goes in the night, who goes in the night…

The association of Isis with the scorpion reaches far beyond ancient Egypt. Athanasius Kircher, a 17th century Jesuit scholar and philosopher, called the constellation of Scorpio “the Station of Isis” and identified the brightest star in Scorpio, the red star Antares, with the Goddess. According to a turn-of-the-century star guide by Richard Hinkley Allen, Antares was originally associated with the Scorpion Goddess, Serket.

Oh, and there’s an Isis comic book in which Isis teams up with The Black Scorpion, another female superhero, so the two Goddesses continue to be linked even in modern mythology.

The Keeper of the Pharos Lighthouse

I don’t know whether I believe in reincarnation; at least in the usual contemporary sense. Oh, I like the idea of it…and it’s quite true that there are some amazing stories people tell of past lives.

Egyptologists, however, are almost unanimously certain that the ancient Egyptians did not believe in reincarnation; presumably, they had enough going on in their afterlives already.

On the other hand, we do have ancient Greek reports of Egyptian belief in reincarnation or the “transmigration of the soul.”

Herodotus writes,

The Egyptians say that Demeter [that is, Isis] and Dionysos [that is, Osiris] are rulers of the world below; and the Egyptians are also the first who reported the doctrine that the soul of man is immortal, and that when the body dies, the soul enters into another creature which chances then to be coming to the birth, and when it has gone the round of all the creatures of land and sea and of the air, it enters again into a human body as it comes to the birth; and that it makes this round in a period of three thousand years. This doctrine certain Hellenes adopted, some earlier and some later, as if it were of their own invention, and of these men I know the names but I abstain from recording them. (Herodotus, Histories Book II, 123)

Diodorus Siculus also reported prominent Greeks who adopted Egyptian teachings, including the transmigration of the soul:

Lycurgus also and Plato and Solon, they say, incorporated many Egyptian customs into their own legislation and Pythagoras learned from Egyptians his teachings about the gods, his geometrical propositions and theory of numbers, as well as the transmigration of the soul into every living thing. (Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, Book I, 98)

Plutarch mentions it, too:

The Egyptians, believing that Typhon was born with red hair, dedicate to sacrifice the red coloured oxen, and make the scrutiny so close that if the beast should have even a single black or white hair, they consider it unfit for sacrifice; because such beast, offered for sacrifice, is not acceptable to the gods, but the contrary (as is) whatsoever has received the souls of unholy and unjust men, that have migrated into other bodies. (Plutarch, “On Isis & Osiris,” 31)

It may be that Herodotus misinterpreted the post mortum transformations of the dead (“Becoming a Hawk of Gold,” for example) as transmigrations of the soul. It may be that Diodorus and Plutarch, writing after Herodotus, just picked up his idea.

Empedokles, a contemporary of Herodotus, refers to “polluted daimons” who are forced to wander the world in many forms “changing one toilsome path of life for another,” though he does not refer to this as being an Egyptian conception. (Empedokles, Katharmoi)

In a number of his works, Plato mentions transmigration as punishment that souls suffer for bad deeds in life. The idea entered the Roman world as well. It can be seen in Virgil’s Aeneid, where reincarnation was seen as a reward for a good soul rather than a punishment for a bad one.

For the Egyptians, the transformations of the dead were simply part of an active and happy afterlife. The dead could become a hawk, a lotus, a serpent…and godlike. Louis Zabkar (an Egyptologist who made an important study of the Isis hymns at Philae) believes that this was a way of ensuring the ba of the person had unlimited freedom to come and go at will on earth and in the otherworld.

Several pharaohs took the name Repeater of Births, which sounds like a reference to reincarnation, but probably isn’t. For Seti I, it apparently meant that he intended to usher in an Egyptian renaissance of sorts. Or it may have referred to the pharaoh’s divine rebirths, which occurred at certain festivals of renewal, or to the the king’s connection to the Sun God Re Who is reborn daily.

All that said, I’d like to share with you one of my (possible?) past life stories.

During a vacation period a while ago, I had the luxury of frequent invocation of the Goddess. While working the Opening of the Ways ritual, I “saw” a flash of a scene that had a deju vu feeling about it, so I decided to follow up on that vision with Isis. Under Her wings, I traveled back in the Boat of Millions of Years to locate the life that included the scene that had touched me. Here is that tale…

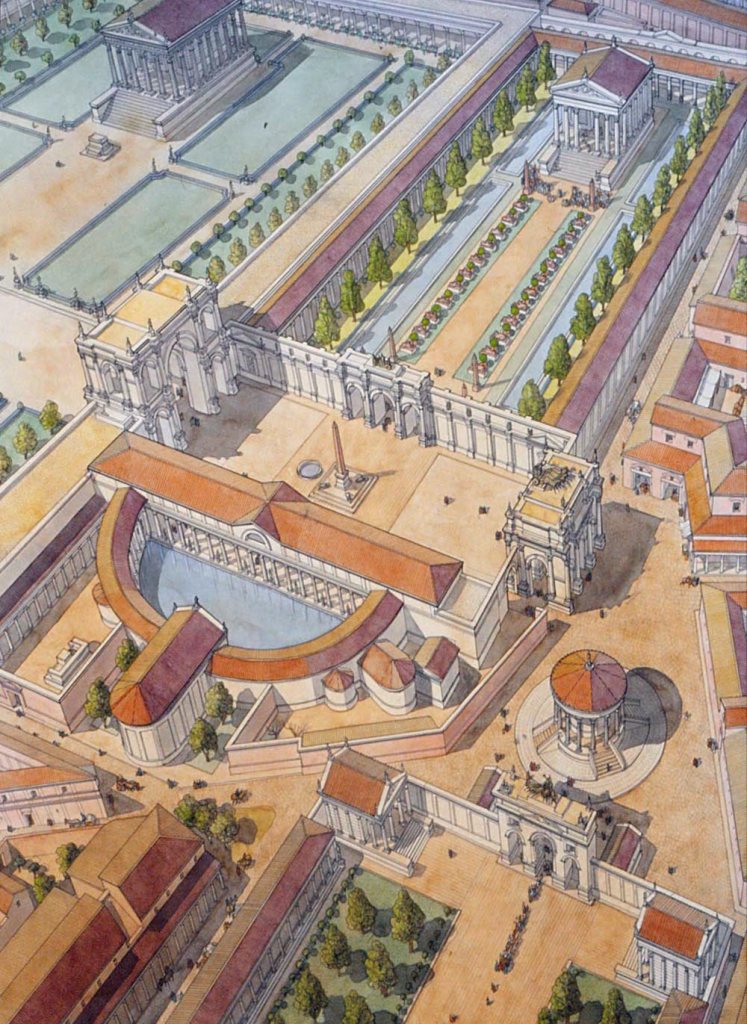

A woman of about 20 is looking out across the Alexandrian harbor. Her name is Ankesphilia and she is the priestess of the Pharos, the Lighthouse of Alexandria. Her duty is to perform something like the Opening of the Ways ritual—but for the opening of the Alexandrian harbor and for fair, “open” weather. This is done within the Pharos itself, about halfway up the structure. That’s where the scene that first caught my attention is from: halfway up the Pharos, overlooking the harbor.

And while Isis is the Goddess of the Lighthouse, it is not Isis who is in Ankesphilia’s heart. Instead, it is her duty to the city that occupies her. Ankesphilia has almost no personal freedom and must stay on Pharos Island at all times, except when there are great festivals in the city. Then she may go to see the processions. I have the feeling that she was “given” or vowed to the Pharos, though it was not her own vow; perhaps her parents? In a way, it reminds me of the later Christian anchorites.

The priestess is from a wealthy, but not noble, family. Her parents own a shipping business, but now her father has retired to the priesthood and her mother runs the business. Her father sometimes visits Ankesphilia at the Pharos. She rarely sees her mother. She has two brothers, both in the military. Though she has had no choice in her fate, I sense no rebellion or resentment in her. I have the feeling she is perhaps not very well educated, bright, or curious. She simply does the duty that has been given to her without complaint and with conscientiousness.

Ankesphilia died in her 30s after contracting a disease that came into the harbor city from overseas.

And that’s it. Past life? Fantasy? I don’t know, but either way, it tells me something about myself.

Isis the Lighthouse Goddess

As one of the most important Goddesses of the ancient seaport of Alexandria, Isis was closely associated with the sea. In that Greco-Egyptian city, She was known by the Greek epithet Pelagia, “of the sea.”

Across the Mediterranean from Alexandria, Roman Isiacs celebrated the festival of the launching of the ship of Isis, the Navigium Isidis, which marked the opening of the shipping season on the sea. It’s the festival described by Apuleius in his ostensibly fictional account of initiation into Isis’ Mysteries in The Golden Ass.

There is another epithet of Isis that connects Her with the sea, shipping, sailing, and the wind necessary for it. It is Pharia.

As Pharia, Isis is connected with the great lighthouse of Alexandria, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World and a famous symbol of the city of Alexandria. The lighthouse was called the Pharos after the small island on which it stood. Due to the lighthouse’s fame, pharos eventually became a general term for “lighthouse.” (This persists even in modern languages; in Italian and Spanish, lighthouse is faro and in French, it is phare.)

Isis Pharia is Isis the Lighthouse Goddess. Alexandrian coins frequently represented the Goddess and the Pharos together.

Roman inscriptions attest to the existence of an Isis temple or shrine on the island, very close to the lighthouse itself. Between 1994 and 1998, archeological divers in the bay of Alexandria discovered a huge, red-granite torso of a woman, the base of an Isis statue, pieces of the Pharos itself, as well as the remains of a rock-cut temple that may very well be part of the temple of Isis Pharia.

There are several legends about how the Pharos island got its name. One says that when Menelaus was returning from the Trojan War, his ship was blown off course and landed on the island. Not knowing where he was, he asked the first Egyptian he saw. The man responded, “Per Aoh,” meaning that the island belonged to the pharaoh. (Pharaoh is the Greek corruption of an Egyptian term for king, Per Aoh, which means “Great House.”) Menelaus heard it as “pharos.”

Another story derives the name from that of Menelaus’ helmsman, Phrontis, who died on the island. In Greek, the word pharos refers to a cloth or sail. In accordance with this punning meaning, images of Isis Pharia show Her with a billowing sail in one hand while Her cloak is blown backwards over Her shoulder and the famous lighthouse stands in the background.

In late legend, Isis was said to have invented the sail while searching for Her son, Horus. The early Christian writer Tertullian, writing against the Pagan religions, says that Pharia’s name “shows her to have been the king’s daughter,” (as opposed to being a true Goddess, of course). Tertullian is surely interpreting Pharia as a feminized version of pharaoh.

Just as the illumination of the Pharos lighthouse turned Alexandria’s dangerous seas and tricky harbors into commerce-friendly ports, the spiritual light of the Lighthouse Goddess serves as a guide for humankind. Isis Pharia is the guardian of navigation and safe harbors—of ships and of souls.

Intrigue & Scandal in the Temple of Isis

Have you heard the shocking—shocking, I tell you!—tale of Paulina and Decius in the Roman Temple of Isis? No? Well, then, as a well-educated Isiac you must, you must. And I’m just the gossip to tell it to you. Here’s the tale, then I’ll join you on the other side for some discussion…

In Rome, in the 1st century CE, there lived a young, beautiful, and rich Roman matron of high birth named Paulina. She was modest, of a most virtuous reputation, and completely faithful to her husband, Saturninus. He, too, was noble and of the very highest character, in every way the equal of his wife. Everybody loved Paulina and Saturninus.

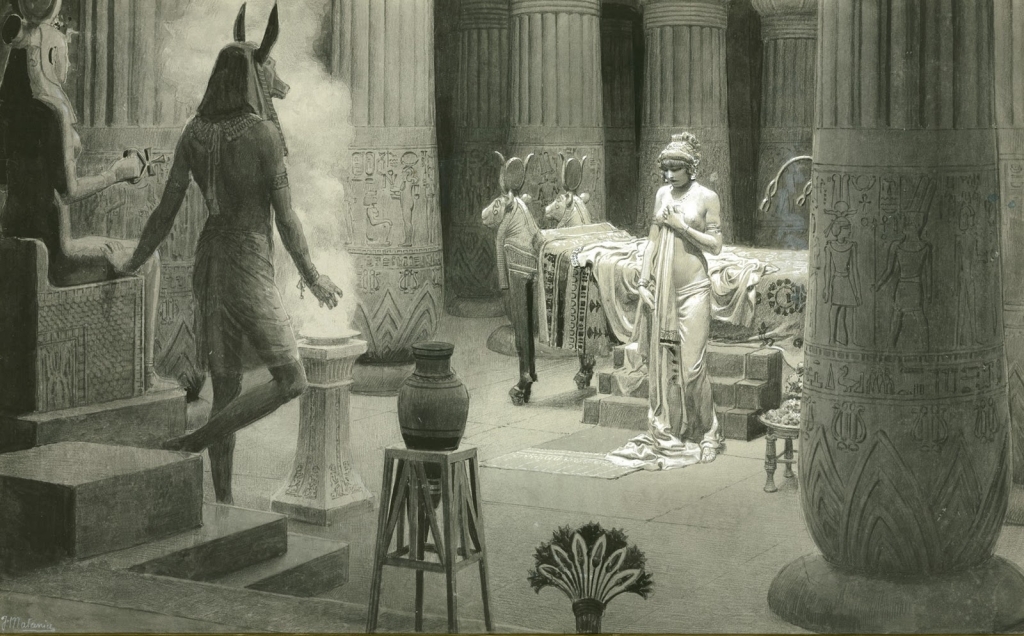

Paulina with pseudo-Anubis on the prowl; this art is by Fortunino Matania (1881-1963), Paulina in the Temple of Isis.

But now, another man enters the scene to disrupt this ideal couple. Of high equestrian rank—we could call him a knight, he “fell in love” with Paulina. I put that in quotes because it was more like “powerfully lusted after,” as we shall see. His name was Decius Mundus and he simply had to have her. He sent gifts. Paulina returned them. He sent more gifts. She returned those, too. Finally—and who knows why he thought this was the way to go—he offered her the outrageous sum of 200,000 Attic drachmae for one night with her.

Predictably, she turned him down.

Drama queen that he was, Decius decided to starve himself to death for want of Paulina. Apparently, he talked about it endlessly.

One of Decius’ servants, a freed woman named Ide, devised a plot that she proposed to Decius. For a mere 50,000 drachmae, she was sure she could get Decius the woman he so histrionically desired. You see, Ide happened to know that Paulina was a devotee of Isis. While lavish gifts and money were not the way to her bed, perhaps religion was.

Ide went to the Temple of Isis and bribed a couple of priests; 25k drachmae now, 25k when Decius succeeds. They agreed and immediately sent one of their number to Paulina. He told her Anubis had given him a message that He was in love with Paulina and wanted to dine and sleep with her. Paulina was flattered. She immediately told Saturninus what Anubis wanted. Apparently he was cool with it, too, so off Paulina went to the Temple of Isis.

Paulina was duly wined and dined without seeing pseudo-Anubis. Then the priests closed the temple and conducted Paulina to the sanctuary, where the lights were put out. Decius leaped out and under the cover of darkness had his way with Paulina. All. Night. Long.

She, rather pleased with the divine experience, went home and proudly told her husband and girlfriends all about it. Her girls were a bit skeptical given the nature of the thing. But since Paulina’s reputation was so immaculate, in the end, they had to believe her.

Three days later, Decius finds Paulina and, sneering at her, admits the whole plot and proves himself to be entirely the asshole we always knew he was. Paulina is pissed. She enlists her husband’s help and he goes straight to Emperor Tiberius. Tiberius has the matter investigated. Eventually the guilty priests and Ide are crucified. The Temple of Isis is razed to the ground. Isis’ sacred image is tossed into the Tiber. And Decius? Merely banished. It was a crime of passion, after all.

Well.

As you can see, this story has almost nothing to do with Isis, except for the venue, some lowlife priests, and, of course, Paulina’s devotion. Aside from its tragicomic-erotic nature, the Paulina story is famous mostly because of the entry right before it in a particular book. The book is Antiquities of the Jews by Flavius Josephus. Josephus’ book is held up as an early source for a historical mention of a certain Jesus, the Christ. (Josephus was ostensibly writing history, so it’s an important mention.) Naturally, there is controversy over whether this is an authentic historical record of Jesus or a later addition by zealous Christians.

Interestingly, the same has been said about the Paulina story. Some have called it a fabrication by Josephus to explain the real persecution of the Jews and the Isiacs by Tiberius in 19 CE. Others say that the gullibility of both Paulina and Saturninus seems more like the plot of a farce than reality. And indeed, there are several similar fictional tales. In the Roman playwright Plautus’ play Amphitryon, Jupiter is sleeping with Amphytryon’s wife, Alcmena, in the guise of her husband. A tricksy slave—who is really Mercury in disguise—confuses things in support of Jupiter’s lustful cause. After some romantic comedy twists, all is well and Amphytryon is okay with sharing his wife with a God.

Then there is the Alexander Romance, which is a highly fictionalized biography of Alexander the Great. Though we mostly know it from Medieval texts, the original has been dated by experts to anywhere from the 3rd century BCE to the 4th century CE. In this story, the Egyptian pharaoh, Nectanebo (both Nectanebo I and II were builders of Isis’ temple at Philae), is also a mighty magician. Basically, he seduces Alexander the Great’s mother, Olympias, by magic, convincing her that she is sleeping with the God Ammon (Amun). Hence the tale that Alexander is a true Egyptian pharaoh by virtue of his Divine father.

It seems likely that the expulsion of the Jews and the Isiacs in 19 CE (as well as other times in Roman history) was more of a political move than retribution for offenses against a Roman matron. During times of internal turmoil, the emperors would stir up the Romans against outsiders (foreign religions, oh my!) and then there would be expulsions or restrictions of some kind. A juicy sex scandal could be the perfect excuse. (For a broader look at Isis in Rome, go here.) On the other hand, it should be noted that Isis devotees in Rome were more known for their religious abstention from sex during periods known as the Chastity of Isis, and not for their licentiousness.

But let’s get back to our sex scandal…

As most of you know, in Egyptian tradition, one did not have temple sex, sacred or otherwise. On the other hand, Egyptian queens did have sex with Gods to produce future kings; it was part of the royal lore. Hatshepsut claimed Amun as her father, the God having come to her mother Ahmose in the form, no doubt, of her father Thutmose I. And Greek and Roman tales have plenty of Divine-human sexual encounters. Hercules is the result of the lovemaking of Jupiter and Alcmene in the play mentioned above.

I’m reading a paper by a scholar, David Klotz, who thinks that sex with Deities may have indeed been going on in temples of the Egyptian Deities during the Roman period. He starts his argument with a tomb painting from El-Salamuni, near Akhmim. Akhmim was known as Koptos to the Greeks. El-Salamuni has a rockcut chapel to Min. Isis and Min were worshipped together at Koptos. As you may recall, Min is the God with the very upright phallus.

So that I do not leave you in suspense, have a look at the tomb painting here. You should be able to click for a larger image. Based on other representations of Anubis in the tomb, they think the naked fellow with the woman on the couch is Anubis as well. Frankly, I can’t quite tell because the head is so destroyed. You?

Klotz mentions that jackals had a reputation for randyness and that an Egyptian dream manual counts it a good omen if a man dreams of his wife having sex with a jackal. In one of the many papyri found in the Oxyrhynchus (Egypt) cache, was an invitation “to dine at the banquet of the Lord Anubis in the oikos [household] of the [probably] Serapeum.” There are also some known stele, funerary in nature, that feature what appear to be dinner and drinking parties taking place with an image of Anubis in the room with the partiers. In some of them, a couple of people are nude or partially nude.

There is also a spell in the magical papyri (PGM) in which the magician first invokes Anubis, then asks Him to bring the local Deities in. Anubis sets up a banquet table for Them, entertaining them until one of the Deities is willing to give an oracle. Anubis is also invoked in some of the non-consensual “love” spells in the magical papyri. At Saqqara, the mudbrick Bes chambers, which featured large images of Bes with smaller images of naked women and in which erotic terracotta votive statues were found, were located in the precinct of Anubis. It is likely that women came there seeking fertility. We don’t know, but it is possible that priests in Godform helped Bes (Anubis?) out in cases like this.

Finally, there are references in Roman literature that connect Anubis with sexy doings. One is the name of a popular farce called The Adulterous Anubis. The other is one of Juvenal’s satiric poems that says priests in the guise of Anubis were the ones who interceded for wives who had not managed to maintain the Chastity of Isis…for a nice bribe, of course.

Klotz concludes that perhaps there was a tradition of priests dressed as Anubis having sex with women in a temple, likely in a quest to conceive a child. So it may be that the fiction of the Paulina story had some kernel of truth—even if the story as a whole does not.

And, you know…maybe. There is a story from the late Pagan period that a couple went to the temple of Isis and actually did come away with a child; a priestess allowed them to adopt her own child. All kinds of propagandistic hay was made over that incident. But it meant that people did continue to come to Isis in a desire for children. And—one way or another—it did happen.

Search For Meaning In Troubling Times

Search For Meaning In Troubling Times

Isis & the Ankh

The awesome scene from “The Mummy” when the statue of Isis raises the ankh to save Her reincarnated priestess from a lovestruck but murderous mummy

Of all the emblems of ancient Egypt, the hieroglyphic symbol of the ankh is probably the most familiar. Many people still wear it as an amulet and know that, in Egyptian, ankh means life.

The ankh was extremely popular in ancient Egypt, too. Egyptians made ankh-shaped vessels, fan bases, sistra, unguent jars, jewelry, mirror cases—in addition to wearing the symbol itself as an amulet. Special bouquets of flowers, formed into the shapes of ankhs and simply called Ankhs, were given as offerings to Deities and as sustenance to the dead. The ankh was carved into temple walls and used to decorate furniture.

In later times, the Coptic Christian church used it as the crux ansata, the handled or “eyed” cross, because of its resemblance to the Christian cross.

Egyptologists still aren’t sure what the familiar oval-and-cross shape originally represented. Some believe it has sexual symbolism because some ankhs have what appears to be a female pubic triangle painted just beneath the cross bar. Others believe it represents a sandal strap. Still others see it as a type of magical knot or bow—similar to the Isis Knot or Tyet, which it closely resembles. Since Egyptian magic frequently employed knots, this idea is not at all far-fetched. Indeed, in some examples of the symbol, you can see what could be folds in the fabric or rope used to tie the knot.

Yet another interpretation combines the knot concept with an idea that may have some merit since it actually connects with the meaning of the symbol itself: life. In this interpretation, the ankh is an umbilical cord that has been looped and tied to a short stick (the cross bar) to create the ankh-shaped amulet. Thus the ankh represents the way Life flows from the Divine to the human in the same way that life flows from the mother to the child through the umbilical cord. There are numerous references to Isis “cutting the navel string” of the reborn Horus. And there is even a myth that Horus recovers the birth cord of His murdered father, Osiris, in order to bury it safely. In a tale about the birth of three kings, the children’s birth cords are cut off, wrapped, and preserved. Clearly, the birth cord had significance.

Yet the life symbolized by the ankh is more than simple daily existence. It is also the sacred and ever-renewing principle of Life. It is the Eternal Life with which the Goddesses and Gods imbue humanity. It is the Life that is renewed after death. In funerary art, Deities such as Anubis and Horus pour streams of ankhs over the deceased to symbolize this eternal, regenerating life that flows from the Divine. Goddesses and Gods hold the ankh to the nose of the deceased to revive her or him in the Otherworld.

While the ankh is rightfully a symbol of every Deity, it is also especially appropriate to Isis. On an earthly level, Isis is the Great Divine Mother, the generatrix of all life on Earth. Isis is intimately connected with the fields that bring forth food, the waters that nourish and regenerate the land, and the life-giving air that fills our lungs.

Isis is a Green Goddess of Life, daughter of Earth and Sky. The Coffin Texts call Her She of Vegetation and Mistress of Herbage Who Makes the Two Lands Green. She is a Water Goddess for Her yearly tears for Osiris caused the Nile to overflow its banks, vivifying the land. She is the Queen of the Sea and the Lady Who brings rain. As a Bird Goddess, Isis is Mistress of the Skies and a Lady of Air.

On a spiritual level, Isis gives the gift of renewed life after death. Beating Her magical wings, the Goddess fans air—and ankh—into the nose and lungs of Her beloved Osiris. It is Isis’ vital breath that fills the nemset jars with which the deceased is dried after a purifying bath. And it is Isis Who brings the spiritual water that helps regenerate the dead.

As She is the Lady of Life, Isis is the Lady of Life Everlasting. She is the Green Goddess of life on Earth and She is the Divine Mother of each of us Who cuts our navel-string when we are transformed and reborn into Eternal Life.

Isis & Mother’s Day

Every year, about this time, I learn from various and sundry newspapers and journals across the land, that Mother’s Day originated in the worship of the Egyptian Goddess Isis.

The idea seems to be that Mother’s Day developed from the ancient worship of Mother Goddesses. And since Isis is THE most well known of these ancient Goddesses, then Mother’s Day had to be Hers, right?

Sorry. Nope. (You can learn the real story, at least as far as the US is concerned, here.)

But, of course, Isis is a Mother Goddess and many, many people have grown their relationship with Isis in Her motherly aspect. So today, in honor of Mother’s Day, I’d like to share with you some lines from a particularly interesting New Kingdom hymn to the Great Goddess.

See if you can guess which Goddess the hymn praises. (When you see […] in the text, it means that the words there could not be read because the source was too damaged.)

“…great of sunlight, Who illumines [the entire land with] Her rays. She is His Eye, Who causes the land to prosper, the glorious eye of Harakhti, the Ruler of What Exists, the Great and Powerful Mistress, life being in Her possession in this Her name […]

[…] in the circuit. The Gods are in […] Great of Might. Her Eye has illumined the horizon. The Ennead, Their hearts are glad because of Her, the Mistress of Their Joy, in this Her name of Heaven.

She is in their hearts, they being glad when She ascends to Her abode, Her temple. She has appeared and has shone as the Woman of Gold […] of best pure silver. All lands give Her their divine property in Her name, and their standards of their places. They rejoice for Her and Her beauty which belongs to Her. Everyone comes into existence through Her when he is created, say the Living in this temple.

There exists no one like Her on earth. She who lives by the might of Her word.

[…] the Great One of the Throne […] She is […] of forms, Great of Property, Mistress of That Which Exists. The papyrus flourishes.”

This Goddess is also called Mistress of the Gods, Queen of Heaven, Great Goddess, Mighty Goddess, Lady of the Two Lands.

While this hymn could well have been used to praise Isis, it wasn’t. It seems that all the Great Goddesses, at one time or another, were called by each other’s epithets and even by each other’s names. Louis Zabkar, who has studied the Isis hymns at Philae extensively, traced how a number of the texts at Philae were adapted from preexisting sources to suit both the space they had available at Philae and the Goddess they were praising.

Yet this particular hymn is in praise of Mut; and it is especially interesting because it is in the form of a crossword. Known as the Crossword Hymn to Mut (obviously enough), the instructions say to read it “three ways.” Indeed, it can be read horizontally and vertically. Scholars guess that the third way might be around the edges, but the artifact is too damaged to be sure that works.

Mut’s name means simply “Mother.” It is spelled with the vulture hieroglyph, which also connects Her with one of the Two Ladies of Egypt, Nekhebet the Vulture Goddess Who was the protectress of Upper Egypt.

According to Horapollo, supposed to be an Egyptian priest or grammarian of the fourth century CE, Egyptian tradition had it that there were no male vultures. Female vultures were thought to remain virgin, but to become pregnant by exposing their vulvas to the north wind. (The north wind was associated with the coming of the inundation and thus with fertility.) Thus Mut is a Virgin Mother. In Her Crossword Hymn, we see Her both as the maiden Daughter of Re and the Great Mother, since everyone comes into existence through Her.

But Mut also has a powerful lioness aspect. In this form, She is one of the Raging and Returning Goddesses, like Sakhmet, Hathor, and Tefnut. In the Book of the Dead, Spell 164, a magical image of Mut is described as having three faces: a vulture, a woman, and a lioness. Not only that, She has a phallus and wings and lion’s claws. The Crossword Hymn shows Her as a fierce and awesome Mother when protecting the dead. Yet it also calls Her Mistress of Joy, Mistress of Peace, and the Beloved One.

Of course, Isis, too, is a Mother Goddess. Specifically and significantly, She is the mother of Horus, Mut Nutdjer, “Mother of the God.” But She also reveals Herself as Mother of the Gods and as the Great Mother of All. As a Great Mother, Isis has inspired the devoted worship of people throughout history. During the Græco-Roman period, Isis’ motherliness toward humanity was expressed in the novel The Golden Ass by Her initiate, Lucius, who declared that Isis brings “the sweet love of a mother to the trials of the unfortunate.” This conception of Isis endures today when, for many, Isis is the very model of the Mother Goddess.

It should be no surprise then that Mother Isis and the Goddess Whose name is simply “Mother” would become identified. In Isis’ Roman-era temple at Shenhur, Isis is represented in four forms: as “Isis the Great, Mother of the Gods,” as “The Great Goddess Isis,” as Mut, and as Nephthys Nebet-Ihy (a festive form of Nephthys). In Mut’s Crossword Hymn, Mut is said to be “under the king as the throne,” just as Isis’ very name means “Throne.”

As Isis the Kite protects Osiris by enfolding Him in Her wings, so in one of the Books of the Dead, a vulture-headed Mut is shown enfolding Osiris in the same way. On a pectoral found in Tutankhamon’s funerary equipment, a vulture, labeled “Isis”, guards the king.

In the Book of the Dead, the “vulture of gold” to be placed at the neck of the deceased is associated with Isis. Both Isis and Mut wear the Vulture Headdress, though Mut wears over it the combined Red and White Crowns. Both are Eye Goddesses and Uraeus Goddesses and as such are assimilated with Bast and Sakhmet. Both, as Great of Magic, take the prominent place of the divine barque to defend and protect the Sun God. And of course, both are Divine Mothers; Isis of Horus and Mut of Khonsu. Isis and Mut are considered to be the mother of the pharaoh and They ultimately mother those of us devoted to Them.

I started this post because I wanted to share with you the amazing Crossword Hymn of Mut. But as I write, I am again struck by this idea of the correspondences between the Great Goddesses of Egypt (and the Great Gods, for that matter). They share mythology. They share epithets. And They share the ability to appear as each other “in Her name of fill-in-the-blank.” This capacity, along with the ancient Egyptian idea that the Deities could combine Their identities or be the Ba-soul of another Deity points at an underlying unity of the Divine in the midst of a thriving polytheism.

Isis, Lady of Fire

Happy May Day and Blessings of Beltane to all who celebrate. In honor of that Festival of Fire, I bring you this post about Our own Lady of Holy Fire…for Isis is a fiery Goddess indeed.

Just as it does at Beltane, in ancient Egypt, fire could represent life and renewal—both very Isiac concepts, as you know.

For examples, during his rejuvenating Sed festival, the king kindled a “new” fire that symbolized his magically renewed life.

The Sun was known to be a living fire Whose birthplace and home is the Isle of Fire. The protective uraeus serpent Who coils on the brow of Re, as well as other Deities and royals, spits poisonous fire and fiery light comes forth from Her throat. Many Goddesses took the form of this fire-spitting serpent, among Them, from an early period, Isis.

The Egyptians also considered fire to be purifying and protective. In Late Period funeral rites, torches were sometimes burnt to cleanse the deceased from any earthly defilement. Flame could be used to drive off evil and exorcise demons. The justified dead could harness the power of fire to protect themselves, or they might even become a living flame themselves. They could drink from the Otherworld lakes of fire without harm, and could even be refreshed by the fiery drink. The unjustified dead, however, had reason to fear fire. They could be plunged into the lakes of fire and eternally tormented by fiery demons. Goddesses and Gods of fire threatened them and fiery gates kept them away from the path to the heavenly realms.

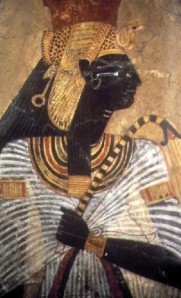

Isis is at Her most fiery when She is in Her aspects as Divine Protectress or as Avenging Goddess. At the entrance to the chapel of Osiris in the tomb of Seti I at Abydos, Isis is called Wosret, the Fiery One, and She protects Osiris from His enemies. At Philae, the king is shown adoring Isis in this fiery aspect; he calls Her his mother and the Lady Wosret.

In one of the hymns to Isis on the temple walls at Philae, She is Nebet Neseret, Lady (or Mistress) of Flame, and She is the fire-spitting uraeus cobra Who instantly destroys the enemies of Re with Her fire and Her potent magic. She is said to assault the rebels and to instantly slay Apophis, the enemy of Re. As the fiery uraeus of Re, She gives orders in the king’s ship.

Isis also partakes of the fiery fierceness of Sakhmet. On one of the gateways, or pylons, at Philae, She is “the mighty, the foremost of the goddesses, daughter of Geb, the sun goddess, the primeval one” and She is identified as “Sakhmet, the fiery goddess.” Yet another Philae hymn calls Her “Sakhmet, the fiery one, who destroys the enemies of her brother.” A papyrus from Oxyrhynchus praises Isis as the Lady of Light and Flames.

This fiery Isis is also connected with initiation, magic, and healing. In Plutarch’s rendition of the Isis myth, Isis nurses the child of Queen Astarte during the day, but at night magically sets the child aflame, making him immortal.

The Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri suggest an explanation for this fire magic Isis works on the queen’s son. The Charm of the Syrian Woman of Gadara says, “the most majestic Goddess’ child [Horus] was set aflame as an initiate.”

Initiation is here seen as purification by fire so that the mortal parts of the initiate are burned away, allowing her or him to more fully understand the ways of the Deities. Some scholars believe that this initiatory fire magic may have had its origins in Egyptian healing magic and what they call the “burning Horus” formula. This refers to an Egyptian convention that connects poisoning with fire. In the same way that the uraeus spits fire, when Horus is poisoned, he is also, in a sense, burned.

Burn-healing formulae identify the sufferer with Horus and say that “a fire has fallen into” Horus, that is, the sufferer. They invoke Isis to put out the fire and heal the burn. The initiatory connection may come from the fact that the poison-burned Horus experiences near-death before being healed by Isis. Mystery initiates, too, regularly undergo symbolic near-death experiences before being saved by the Goddess or God of the Mystery Rite.

Isis is Iset Wosret and the fire-spitting Cobra Goddess. She is the Mistress of Light and Flame Who slays evil and protects us all. And She is the one Who not only initiates us by fire, but also warms us by Her illuminating light.

The Queen of Heaven

The three titles of the Divine Daughter are Princess of the World, Priestess of the World and Queen of Heaven. The May Day festival, the final festival of the Easter season, celebrates the Daughter as Queen of Heaven. The crowning of the Queen of Heaven is often reflected in celebrations by the crowning of statues or of a chosen May Queen. Read more about the Exaltation of the Queen of Heaven

The Queen of Heaven

The three titles of the Divine Daughter are Princess of the World, Priestess of the World and Queen of Heaven. The May Day festival, the final festival of the Easter season, celebrates the Daughter as Queen of Heaven. The crowning of the Queen of Heaven is often reflected in celebrations by the crowning of statues or of a chosen May Queen. Read more about the Exaltation of the Queen of Heaven

Learning To Endure The Intolerable

Learning To Endure The Intolerable

Women as Priestesses in Ancient Egypt

Our topic today? Sexism in egyptology.

Well, it’s actually priestesses in ancient Egypt, but it was a bunch of sexist assumptions by previous generations of egyptologists that allowed the importance of priestesses to be overlooked or discounted and inspired me to choose this topic for the post.

What sort of sexist assumptions you say?

Many old-school egyptologists have assumed that women were not allowed to participate in the most holy—that is, most important—aspects of worship. They have assumed that the sacerdotal titles of high-status Egyptian women were simply honorary and the women did not actually perform the work of a priestess. Such assumptions are never made when it comes to Egyptian men with corresponding titles. Never. By translating the Egyptian term, Servant of the God—which was used of both men and women—as priest or priestess, the old gentlemen were allowing themselves a little mental sexism for, in their minds, a priestess was always of lower status than a priest because in their society women were of lower status than men. It was assumed that the religious involvement of women with priestly titles was not “professional” and when Egyptian religion became “more organized” in the New Kingdom, there was an effort to exclude women.

Sheldon Gosline, the author of a scholarly article I’m reading on this topic, believes this assumption is mainly based on Christian and Jewish exclusion of women from priestly activities rather than on any real evidence from Egypt. There has also been the assumption—less these days than it was, thank Goddess—that women’s roles in the temple were mainly sexual; that the female musicians were some sort of harem (because music is inherently sexual, you see) and that the God’s Wife, another priestessly title, was supposed to have sex with the priests of the temple who represented the God. Such assumptions were, no doubt, based on statements like this one from the Greek geographer Strabo, himself hailing from a supremely sexist culture. Says Strabo:

“To Zeus [Amun] they consecrate one of the most beautiful girls of the most illustrious family . . . She becomes a prostitute and has intercourse with whoever she wishes, until the purification of her body [menstruation] takes place.”

(We are always hearing tales of temple prostitution, are we not? It’s just so…so…well, pagan.) In fact, there is no evidence of Egyptian temple prostitution or that priestesses were expected to have sex—sacred or otherwise—in the temple. In fact, the opposite is true; one was decidedly NOT supposed to have sex in the temple. (None of this is to say that sex had no place in ancient Egyptian religion and culture; it did, and an important place. But that’s a topic for another day. And that other day has come. Here’s the article about that.)

Thankfully, more modern egyptologists are taking a less biased view.

So what’s the real story?

Unfortunately, due to the incomplete nature of the evidence, we can never be entirely certain. Yet we do have the opportunity to look at what evidence remains in a fresh way. When we do so, we notice that we have records of quite a large number of ancient Egyptian priestesses. These records come from all periods and regions of Egypt. We see that supposedly honorific titles were borne by some women who were not married to priests or who were married to men of lower rank. In other words, the woman’s status was her own and she did not derive it from her husband. From the fifth dynasty we have a record that shows that the sons and daughter of one noble family took turns being the Servant of the God of Hathor. The religious duties of the sister Servant of the God would have been the same as those of the brother Servant of the God or it would not have been possible to switch off like that. We also have records showing that lower-ranked priestesses and priests were paid exactly the same amount for their temple service, which must indicate the equal importance and likely equal duties the job entailed. We have evidence that the priestessly title of Meret, “Beloved,” may have been quite a high-ranking position. At least one Meret priestess was responsible for the financial security of the temple through care for its real estate and agricultural resources—a very important role and one that must have required a great deal of education and experience.