Those of you who have been following this blog for a while may be familiar with my small rants about The Old Gentlemen of Egyptology and their innate sexist attitudes. Well, today it’s time for another rant…just a little one…but this time it’s about the Even Older Gentlemen of Ancient Egypt and their innate sexist attitudes.

You see, I just came across a scholarly article by Carolyn Routledge entitled “Did Women ‘Do Things’ in Ancient Egypt? (c. 2600-1050 BCE)” at the same time as Academia.edu served me up a thesis by the same Carolyn Routledge about ancient Egyptian ritual practice, which was an in-depth study of two specific words having to do with ritual, one of which translates as “doing things” (iri ḫt).

Routledge explains that the Egyptians used ir ḫt (“to do things”) in several specific ways. In addition to its meaning as ritual performance, including funerary rites, it also has to do with the performance of work or duty, and even negative behavior. It was used particularly in relation to physical activity.

Of course I’m most interested in ir ḫt meaning “to do ritual.” The kinds of ritual activities that were Done included libating and censing and making offering: “you perform rites [iri ḫt]; bread, beer, and incense upon the flame.”

Interestingly, there also seems to be some emphasis on doing these things with one’s arms and hands. Makes me wonder whether, in addition to the sheer physicality of using a sacred vessel to libate, a censer to burn incense, or employing some other ritual object, there was also supposed to have been an accompanying gesture. There also seems to have been a connection to written instructions in the performance of ritual. So the lector priest, the sacred reader, was one who definitely Did Things.

If one wanted to be quite specific, one could also say he was iri ḫt nṯr, “doing God’s rites” or iri ḫt nṯrt, “doing Goddess’ rites.” But notice that pronoun I just used in relation to the person doing the Doing? Yeah. He. Sadly, Routledge answers the question posed in her article title with a resounding no; women did not Do Things. At least as far as we can tell from the evidence left to us, and I must admit it seems reasonably conclusive.

For example, the king has the title, neb ir ḫt, “Lord of Doing Things.” It is often used in connection with the king Doing Things that maintain Ma’et, including cultic functions as well as kingly duties and activities. The queen, however, does not Do Things. She has no title, Lady of Doing Things. Instead, she “says all things and it is done for her.” I used to think that was a nice expression of queenly power; now, I’m kinda thinking it’s the opposite: an expression of the perceived inability of women to Do Things themselves.

There are only two exceptions: Sobeknefru and Hatshepsut, both women who ruled as king, not queen. In Hatshepsut’s case, about half of the references to that title are in the masculine form, half in a feminized form: nebet ir ḫt. (We have no references to Tausert, a later woman ruler, having that title.)

The exclusion of women from Doing Things is, of course, the basis of my rant. Or maybe it’s not even really a rant. More of a whine. Or an exhausted, put-upon sigh.

The king, priests, and officials of all stripes Did Things. But when it came to women, the “things” part of the important phrase was avoided. There are instances of women iri irw, “doing doings” or “performing performances,” but not iri ḫt. Routledge gives an interesting example of a husband and wife, both named Djehutynakht, both with the same funerary text on their coffins, but hers excludes the word ḫt.

It’s practically impossible not to smell the old sexist weakness-of-women, unfitness-of-women-for-important-stuff stereotypes here. But we don’t know. Routledge suggests that it may be because iri ḫt was associated with educated, literate, and highly trained people, very few of whom would have been women in ancient Egypt. True enough. But the question underlying that conclusion is “why not?” Which, of course, refers us back to the first sentence in this paragraph.

So what can we do with this information? Why am I sharing it with you?

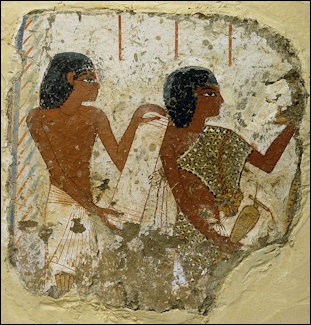

First, I enjoyed learning an important ancient term for doing ritual and reading about its specific connotations. Second, we sometimes tend to idealize the ancient Egyptians—we do so love their Deities, their art, their magic and mysterious ancient wisdom. It is important to know that every society—theirs, ours, everybody’s—has flaws, often significant ones, and we should not be blind to them. And in our own case today, we must work to fix them.

And third? Third, I hope to encourage all of us to Do Things for Isis. We all have the capacity for Doing Things in the ancient sense: with power, purpose, and effectiveness. Let us also be reminded that the physicality of ritual is important. For when we are fully engaged with what we are Doing—body, mind, soul, and spirit—ritual is far from being empty show. It is instead Right Action that can truly Open the Ways so that we may come, once more, to the Divine Heart of Isis.