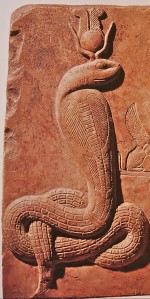

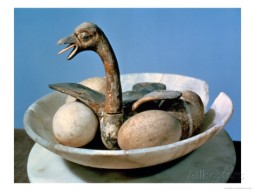

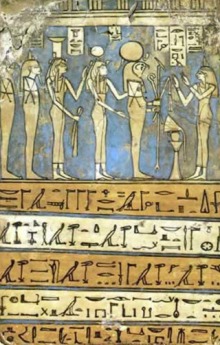

The ancient Egyptian amulet of the Tiet (also Tyet or Tet) is also known as the Girdle of Isis, the Buckle of Isis, the Knot of Isis, or the Blood of Isis. Appropriately, the amulet was often made of blood-red jasper, carnelian, or even red glass. (Red glass, by the way, is a precious material and quite difficult to make; the red color comes from the addition of gold to the molten glass.)

When paired with the Djed of Osiris, the Tiet can be seen as the feminine symbol of the Goddess’ womb just as the Djed can be seen as the masculine symbol of the God’s phallus.

The redness of the Tiet may represent the red lifeblood a mother sheds while giving birth. On the other hand, it might represent menstrual blood. Some say the amulet is shaped like the cloth worn by ancient Egyptian women during menstruation. Others have interpreted it as a representation of a ritual tampon that could be inserted in the vagina to prevent miscarriage. In this case, it would have been the amulet Isis used to protect Horus while He was still within Her womb. For a whole post on the Knot of Isis, click here.

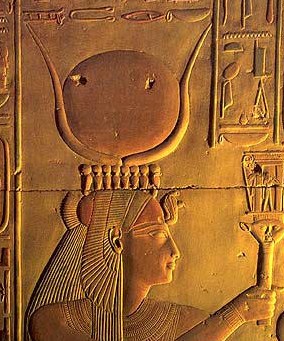

The Goddess’ blood that is our topic today is the red blood of menstruation, in Egyptian hesmen. A menstruating woman is a hesmenet. If the interpretation of the Knot of Isis as a menstrual cloth or tampon is correct, we may be well within our rights to consider Isis as the patroness of women during their monthly menstruation as well as a special patroness of women during the fertile period of their lives, this is, while they are still menstruating regularly.

A young woman’s first menstruation is a sign that she is now mature enough to become pregnant, thus the ancient Egyptians considered menstrual blood to be very potent. One of the methods a woman might use to encourage her own pregnancy was to rub menstrual blood on her thighs. The Ebers papyrus notes that the blood of a young woman whose menses have just come could be rubbed on the breasts, belly, and thighs of a woman whose breasts were too full of milk, “then the flow cannot be to her disadvantage.” Menstrual blood might also be used to anoint infants to protect them from evil. Could it be that the Tiet amulet was developed as a more convenient way to protect children, and by extension adults, from harm through the menstrual Blood of Isis?

We have very little from ancient Egypt about women’s menstrual customs. There is one precious mention on an ostracon (piece of pottery used as a writing surface) that scholars believe originated in Deir el-Medina, the workers’ village outside the Valley of the Kings. It says,

Year 9, fourth month of inundation, day 13. Day that the eight women came outside [to the] place of women, when they were menstruating. They got as far as the back of the house which […long gap…] the three walls …

From this reference, scholars infer that ancient Egyptian women, like many women throughout the ancient world (as well as some in the modern world) separated themselves from the rest of the village during their menstrual periods and went to “the place of women.” What’s more, at least eight women from this village were on the same cycle. But I wonder why this common, monthly event was significant enough for someone to write it down? As far as I can tell, no one has a guess.

None of the “places of women” have been found for certain, though there are several small structures on the outskirts of Deir el-Medina that could possibly fit the bill. Interestingly, at Deir el-Medina, the menstruation of wives or daughters is sometimes given as a reason for the man’s absence from work. The weird thing about this is that, if a man could be absent every time a wife or daughter had her period, he’d be absent at least two extra days per month…and we don’t find that many absences recorded. This has led some researchers to suggest that only in exceptional cases, for example if the woman was incapacitated by her period, could the man be absent to take care of the regular household chores.

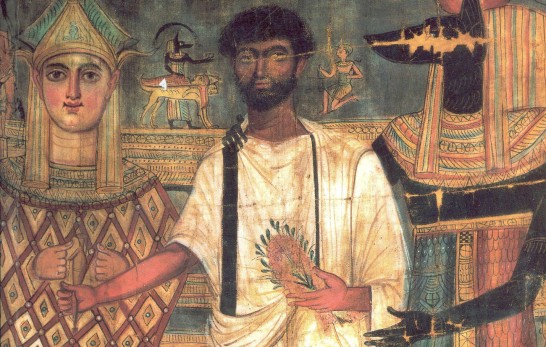

The other reference to a place of menstruation comes from much later—in the Ptolemaic period—when we find a reference to a “place beneath the stairs,” actually within the home, as the place of menstruation. This room must have been reasonably common for we find reference to it in a number of documents related to the sale or purchase of a home. I am imagining some ancient realtor noting the lovely little “place beneath the stairs” as a selling feature of the house. (It should be noted that a woman was the seller in at least one of these real estate transactions and in another, a woman was the buyer; more evidence of women’s relatively high status in Egypt.)

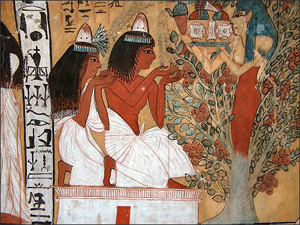

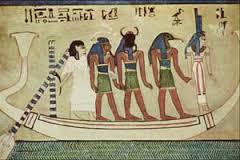

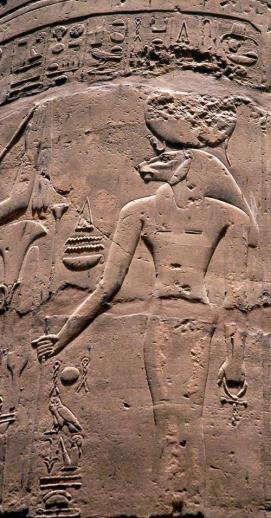

In a house in Amarna, in just such a place beneath the stairs, archeologists found two model beds made of clay, parts of two female figurines, and a stela depicting a woman wearing a cone on her head while leading a young girl before the Goddess Taweret. That all seems pretty clear to me; this is where women go to menstruate and where they celebrate the coming of age of young women, who are being introduced to Taweret, the hippopotamus-form Goddess of pregnancy and childbirth.

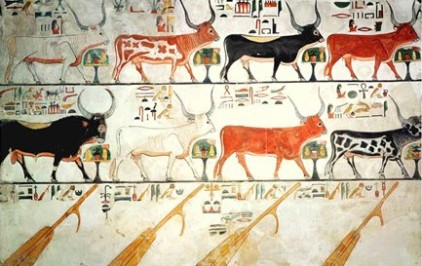

These special places for menstruating women seem to indicate a taboo around menstruation; the women absented themselves from the village or stayed in a special room. We also have lists of bwt, prohibitions or “evil”, in the 42 Egyptian nomes and some of them include menstruation and menstruating women—along with things like a black bull, a heart, and a head. We’re not sure in what way any of these things were to be prohibited; perhaps by keeping them out of the nome? At any rate, menstruation in these cases was seen as something negative.

There does not seem to have been a notion of actual pollution around menstruation or menstruating women, however. Contact with a menstruating woman was not dangerous to a man, even though she was bwt in some nomes. In fact, some scholars think it was the menstruating woman who needed protection during her period. Thus, in the case of the absent workers of Deir el-Medina, the workers stayed away from the death-touched tombs in which they were working in order to protect their menstruating female relatives. Conversely, the Egyptians may have wanted to prevent the non-pregnancy/fertility of a menstruating woman from touching the cosmic womb of the royal tomb through her male relative, and thus rendering it magically ineffective.

Interestingly, it may be that menstruation was also associated with cleansing. Hesmen is not only the word for “menstruation,” but is also found with the meaning “purification.” It was also a term for the ritual cleanser par excellence, natron.

From the evidence, menstruation in ancient Egypt had both positive and negative connotations. On the one hand, it was a sign that a woman could become pregnant—something most women desired—and it was used as a potent protection or cure. On the other hand, if one was menstruating, one was clearly not pregnant at the time, so menstruation might be incompatible with work on the magical womb of the tomb, which must be kept fertile at all times.

I think many women would agree with this ambivalent attitude toward their periods. Having a period is at once a beautiful confirmation of connection with the cycles of Nature and the Great Goddess, and it can be a painful and messy time, too. In whatever way we are currently experiencing those cycles, we can be sure that the protection, as well as the shared female experience, of the Holy Blood of Isis is with us. I don’t know about you, but I think I may put on my Tiet amulet today.