This summer, we’ll be celebrating a festival for the Wandering Goddesses, Hathor and Sakhmet. The myth of the Wandering Goddess is one of the most important myths of ancient Egypt. Almost every locality had their own version of the story and their own Wandering Goddess. So, I’m going to repost my Wandering Goddess series—while I work on new posts and attend a Board meeting today. I hope you find it interesting.

Part 1

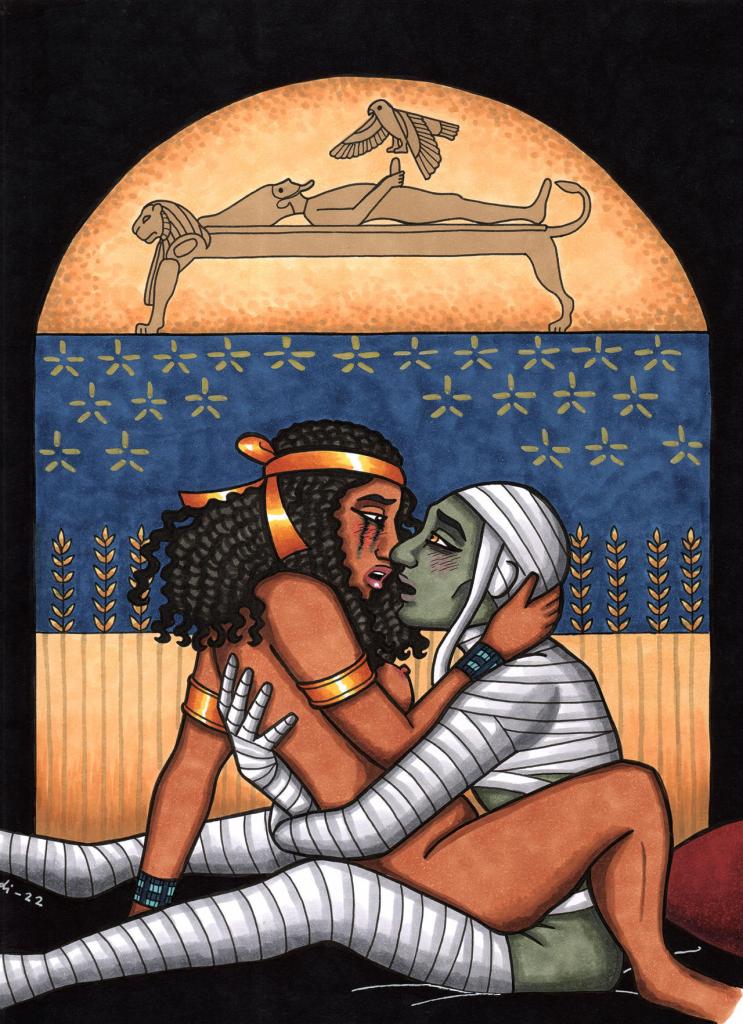

If your first reaction is, “Well, heck yeah; She wandered all over looking for the bits of Osiris,” you would not be wrong. But I’m thinking of a different wandering Goddess motif—and not one that is usually associated with Isis.

This mythic theme is also known as the tale of the Distant Goddess, the Wrathful Goddess, or the Returning Goddess. Most people are familiar with it from the Egyptian text known as the Book of the Heavenly Cow.

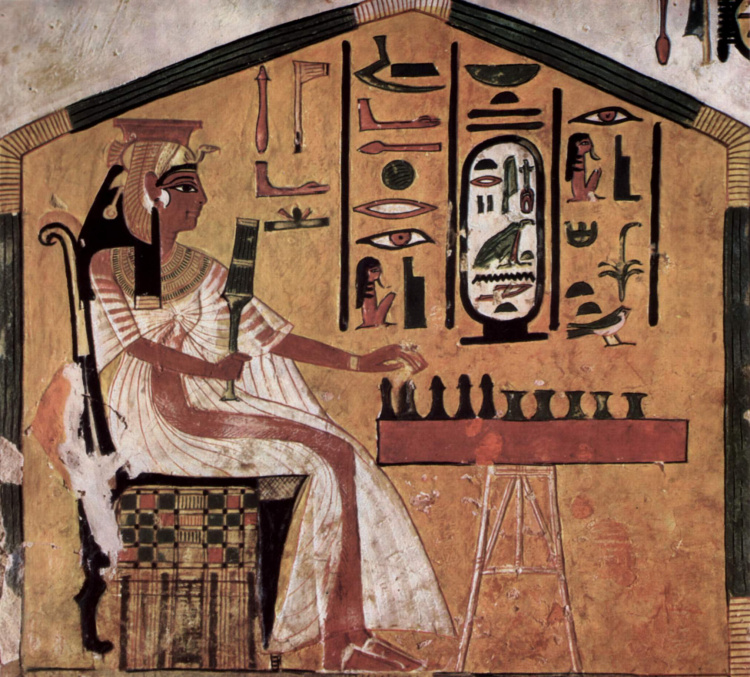

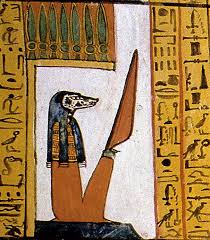

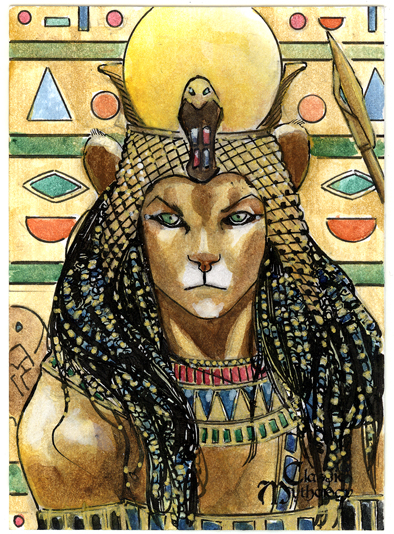

In that story, humanity has rebelled against Re and He sends Hathor—Who becomes the much-more-violent Sakhmet—to punish them. She enjoys Her work so well that Re is afraid She might wipe out all of humanity. To quell Her berserker rage, beer is colored red. Lioness Sakhmet laps it up like blood, becomes drunk…and is thus “pacified.” Egyptian festivals celebrated Her peaceful return to Her father Re with all-around drunkenness—and not a few hookups on one hand and mystical communions with the Goddess on the other.

But there are many other Goddesses Who share this mythic motif. While the details—to the extent that we have them—are different in the different tales, let’s take a brief look at Who-all-else may have been involved.

In the second most well known of these tales, it is Tefnut Who is our Wandering Goddess. We have a Demotic (late Egyptian) version of the tale and a Greek folktale-ish one. Both are spotty as the papyri are quite damaged and neither has been translated into English, so I’m working from paraphrases.

As our story begins, Tefnut—one of the Fiery Feline Goddesses of the Eye—is angry. She is the Eye of Re, Who, in this version, is Her father. We don’t know why She is angry, but She leaves, heading south, possibly to Nubia or to some other place That Is Not Here.

Without His powerful daughter, Re is vulnerable, so He sends Shu, Tefnut’s husband and brother, and Thoth, Who is particularly clever at pacifying angry Goddesses, to fetch Her back. Eventually, They track Her down. It takes some doing, but with entertaining stories, promises of offerings and festivals, jars of beer, and the wensheb, the symbol of ordered time (and general ma’et-ness), the Fiery Goddess is persuaded to return to Egypt and Her father.

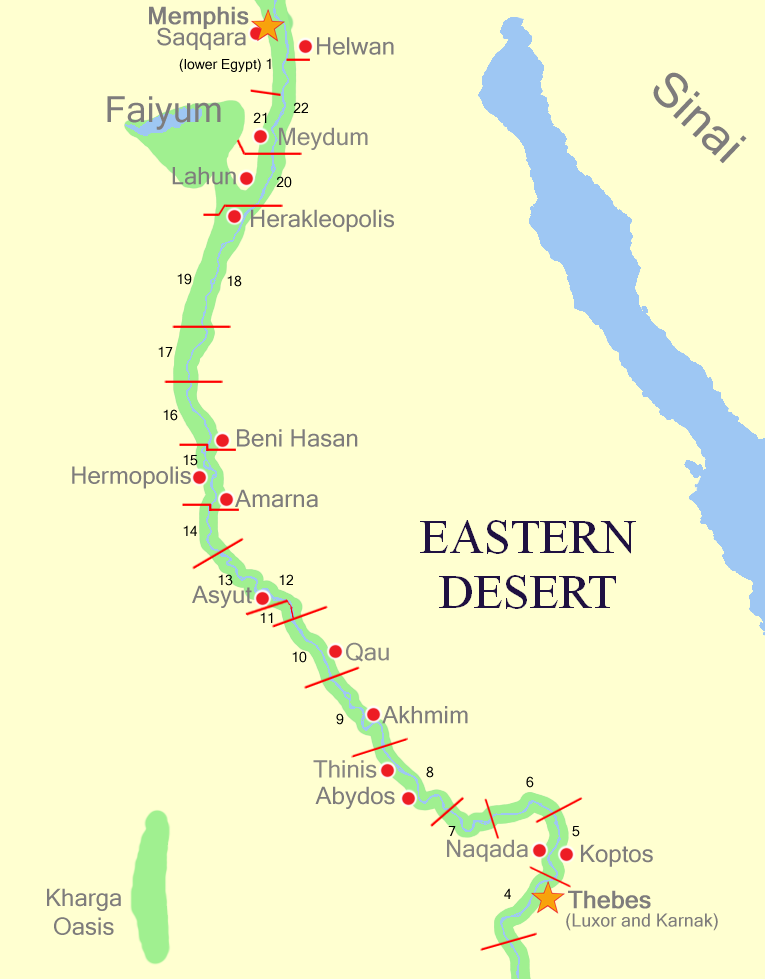

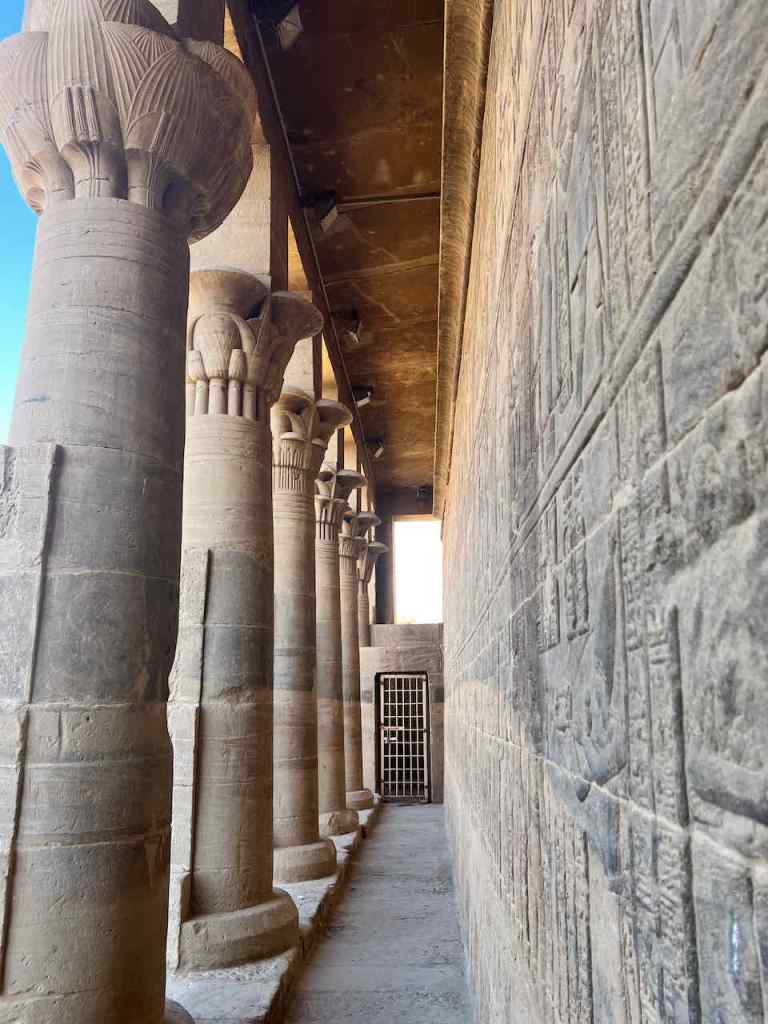

The first place She stops on Her way back into Egypt is the southern Egyptian temple of Isis at Philae. There, She is purified and transforms from Her Burning Lioness form into a lovely woman. On the nearby island of Biggeh, where a tomb of Osiris and an Isis-Osiris temple were located, we find also a temple to Tefnut-Hathor, our angry/joyful Goddess. Perhaps this temple was Her starting point as She traveled from southern Egypt to northern, stopping at temples and towns along the way.

At each stop, a joyous welcome-home-and-restoration-of-order festival of music, dancing, drinking, and feasting ensues. (I am reminded that in cultures throughout the world—often—festivals of license are required in order to usher in a renewed period of order.)

Warning: references to rape in myth upcoming.

Another of Tefnut’s Wandering Goddess myths is darker. We have bits of it from papyri found in the Faiyum and the Delta and on a naos from the 30th dynasty. From these sources, we learn that Geb has raped His mother Tefnut and taken the kingship from His father Shu, recently deceased, though we’re not sure how Shu died. Another version of the myth says Geb “hurt His father Shu as He copulated with His mother Tefnut.” In the next sentence, Tefnut leaves—surely blazing with anger, though what we have says nothing of Her state of mind. During Her absence, the text says, “the lance was placed in His [Geb’s] thigh,” in punishment. Another version has Geb taking up the royal Uraeus of Shu and placing it on His own head, but it burns Him ferociously with a wound that won’t heal. (And we recall that the royal Uraeus is yet another form of the fiery Eye Goddess.)

There are many confusing details in these myths that I won’t go into here. But I do want to again call out the reason why the outraged Goddess leaves, going as far away as She can: She has been raped by Her son.

In a different post, we looked at another raped-Goddess myth, the story of Horit. We don’t hear of Horit leaving for somewhere That Is Not Here. While being identified with Tefnut, She is instead imprisoned—in Sebennytos, the Lower Egyptian capital of the nome where Isis’ temple complex at Isiopolis was located. Eventually, She is freed. So, the Return of the Goddess, in this case, is a return from imprisonment…with the same joyous welcome from the people.

From Upper Egypt, there is the story of Mehyt and Onuris. Onuris, the desert hunter, is the consort of the Lioness Goddess Mehyt. His name means something like “Bringer of the Distant One” and Her name means something like “the Full One.” It may relate to Her identification as the Udjat Eye of Horus, that is the full Eye or the full moon. Mehyt, like all Eye Goddesses, is a protective Goddess, and protects both Osiris and Re. She is also a Fierce Goddess wielding arrows or hoards of demons as needed. As Onuris is involved in a hunt for the Eye of Horus, His heart is said to ache for the Sacred Eye, which certainly seems to make The Eye less of a thing to be procured and more of…well…a Goddess to be desired. Mehyt and Onuris were also honored in Lower Egypt; there was a temple to Them at Sebennytos.

There were many local versions of the Distant Goddess theme. Frequently, the raging Goddess goes by one name and the pacified one by another—like Sakhmet/Hathor in the Heavenly Cow. At Hermopolis, the fiery Goddess is Ai or Tai, while the peaceful one is Nehemant. Demotic inscriptions from Herakleopolis, where these Goddesses were also honored, show evidence of a festival of drunkenness for Her, as it seems there may have been for all our Returning Goddesses.

Inscriptions tell us that “when they are drunk, they will see . . . by means of the vessel” and that people make love before the Goddess and celebrate Her with feasts. From Tebtunis (in the Faiyum), Wenut (Who we met here) is the Raging Goddess and Nehemtua is the Returning One. Nehemant/Nehemtua (and other, similar renderings of Her name) is, predictably, identified with Tefnut, Horit, and Hathor.

Instead of Nubia, Nehemtua has fled to Naunet, the Great Goddess of the Hermopolitan Abyss, and settled Herself within Naunet. Here, we do know why She fled: because Set wants to possess Her, both sexually and as a symbol of His father Geb’s kingdom. So again, the Goddess is fleeing either post-rape or to prevent it. In this tale, it is Thoth and Nephthys Who go to bring the Goddess back.

Upon Her return, Nehemtua is said to have been “initiated” (bsi) to Shu (reinforcing Her connection to Tefnut) in the great (sacred) lake at Hermopolis. Frequently, water is required to cool down the fiery Goddess.

The Great Goddess Mut, Whose name means simply “mother,” is also associated with this theme. She is the Lady of the Isheru,* the crescent-shaped sacred lake in which the Raging Goddess is cooled and, no doubt, purified upon Her return. Part of Her ecstatic festival of return was called the Navigation of Mut and was enacted upon the cooling isheru. Some semi-recently come-to-light texts have made Mut’s festival of drunkenness rather famous. A very fragmentary text about these festivals refers to “the Distant One” and to pacification of the Goddess. We learn of singing, dancing, drinking, feasting, and “sexual bliss” in honor of Mut. Pharaoh Hatshepsut is recorded as having built a “portico of drunkenness” for Her.

Also of note is Mut’s ability to renew Herself; She is both mother and daughter. Her consort is Amun, Who is capable of self-renewal, too, for He bears the epithet Kamutef, Bull of His Mother. And yes, the bull part refers to sex. So we have Mut and Amun (and Re, as possessor of the Eye, is in there somewhere, too) as mother and daughter and son and father to each other. The God Min of Koptos is also called Kamutef—with Isis as His mother/sexual partner. With the Isis-Horus connection so strong, Min eventually takes on the name Horus as well.

And this is by no means the end of the Egyptian Goddesses associated with the myth of the Wandering Goddess, but it is enough to get a picture of its widespread nature. Egyptologists’ explanations for its origins include: the sun’s movement southward from summer to winter; the heliacal disappearance and return of the star Sirius to herald the Inundation; the waning and waxing of the moon during its cycle; the Inundation itself as its waters quench Egyptian fields and cool the red-hot Goddess; the hunter bringing back a tamed animal to his tribe; the maintenance of royal power; the return of ma’et after a period of disorder; and a young woman’s first menstrual period—wherein she leaves as an immature girl, but returns as a sexually mature being, a possibility I find intriguing. Oh, and let’s not forget (in some cases) rape as the reason for the Goddess’ departure and the “sorry, come back home, baby” nature of the persuasions—to put another human face on it. All of these make some sense and there doesn’t have to be just one answer.

As I said in the beginning, we don’t usually connect Isis with this myth. We have no stories left to us in which Isis rages off and has to be persuaded to return, from Nubia or anywhere else. We know of no festivals of drunkenness for Her. And yet, I feel almost certain that there used to be just such a tale. We’ll talk about that next time and I’ll lay out my case.

*As you might guess, Sakhmet and Bast, both feline Deities, were known to have isheru…but Wadjet had one, too. Usually, we think of Her in the form of the Uraeus Goddess, but She also had a lioness form—and is thus among our Fierce and Fiery Felines, too.