Part 2

Last time, we wondered whether Our Lady Isis might be one of the Wandering/Distant/Returning Goddesses of ancient Egypt. And while we don’t have myths of an angry Isian departure or a festival of drunkenness for Her, I still think there are enough traces left to connect Isis to this important Egyptian mythic theme.

Let’s start at Philae, the location of Isis’ great Upper Egyptian temple, located near Egypt’s border with ancient Nubia. As you might recall, Philae was Tefnut’s first stop upon that Goddess’ return to Egypt following Her angry flight to Nubia. An inscription on Isis’ temple there says that when Tefnut arrived, there was a great flame around Her, but then She went up into the sky 10,000 cubits and immediately became peaceful.

Egyptologist Joachim Quack suggests an astronomical solution to the burning lioness’ aerial ascent: the heliacal rising of the star Sirius, which twinkles red close to the horizon, but as it rises higher takes on a calmer, blue-white color, and which—thousands of years ago—heralded the beginning of the vital Egyptian Inundation. The temple at Philae, in ancient Egypt’s far south, would have been one of the first places observers could have witnessed the heliacal return of the star.

The star’s behavior, apparently leaving the sky for a period of about 70 days each year while it is in a too-close conjunction with the greater light of the sun, works well with the myth. The Goddess disappears for a while, then returns to the rejoicing of the people, for as She returns, She brings with Her the floods that ensure the fertility of the land. What’s more, some of these festivals for the Returning Goddess seem to have taken place around the summer solstice. Depending on when in time and where on earth you were or are, the summer solstice could coincide roughly with the rise of Sirius.

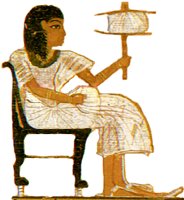

So…here in Isis’ temple on the border of Nubia, we have Isis’ own grandmother Tefnut, identified with the star Sirius, which is itself personified as the Goddess Sopdet, a Goddess Who has been identified with Isis since at least the time of the Pyramid Texts. If we appreciate the Sirius solution as a possible origin for the myth of the Wandering Goddess, it’s a pretty easy, pretty clean Distant/Returning Isis connection.

Of course, if you’ve looked into Egyptian myth, you know that most of it doesn’t come in clear, narrative form. The only reason we have a narrative-ish version of the Isis and Osiris story is that the Greek priest Plutarch wrote it down like that.

As a source for the story of Tefnut as the Returning Goddess, we have the Demotic and Greek versions I mentioned last time, but mostly what we have are bits and pieces from temple walls, monuments, funerary texts, and texts like the Delta and Tebtunis mythological manuals. And while the overarching theme is the same—Goddess goes, bad; Goddess returns, good—the details are different enough that no one has tried to put together any such thing as a definitive version of the myth.

So, to track down our Wandering Isis, I’ll try to pull together some of the pieces of Her story that seem to relate to the main features of the myth/s as we know them.

The Angry Goddess

One of the first things you may have noticed is that our Distant Goddesses all have a lioness form. Most people are familiar with the lioness forms of Sakhmet-Hathor and Tefnut, but the other Distant Goddesses are lionesses, too. As the pride’s main hunters, lionesses are decidedly fierce. Even lions back off in the face of an angry lioness; you’ve seen the videos.

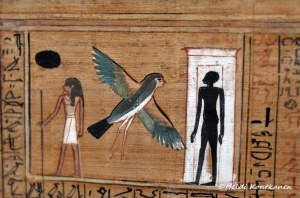

And yes, even glittery Sopdet has a lioness form. If you’ve been following along with this blog, you already know that Isis Herself can appear as a lioness and is frequently identified with Sakhmet or Bastet, just to name two of our most prominent Feline Goddesses. Isis’ Philae temple entrance is guarded by two lion statues and She is often shown seated upon a lion-throne.

Horit (read about Her here and here) is lioness connected, too. Like Isis, She is repeatedly identified with some of our fierce feline Goddesses. One of Her children is killed by a lioness. The lioness is hunted down by Nephthys and Thoth and flayed. The remains of the child are wrapped in the lioness’ skin and the child is reborn.

Another part to Horit’s myth makes Her a duplicate of Isis. One of the children She bears to Osiris is Horus of Medenu. When Osiris is killed by Seth, Horit hides Her Horus in the marshes, raising Him to be an avenger of His father Osiris—just as Isis did with Her Horus, Harsiese “Horus, son of Isis.”

Further, Horit is imprisoned in Sebennytos where She is connected with Tefnut, Sakhmet, Bastet, and Hathor. Sebennytos also had a temple of the lioness Meyht and Her consort-hunter Onuris. Just a few miles from Sebennytos is the location of the Lower Egyptian temple of Isis known (later) as Isiopolis with its focus on the resurrection of Osiris. So right here, in this part of the Egyptian Delta, we find temples and myths that incorporate both the Returning Goddess and Isis-Osiris themes. What’s more, we have a duplicate Isis—Horit—Who forms a kind of bridge between these two important motifs.

Another characteristic of our Distant Goddesses is that They are angry when They leave. In some cases, we know why; in others, we don’t. And while many people think of Isis as an exclusively kind and motherly Deity, She can also show an angry-burning-lioness side and be kick-yer-ass insistent from time to time.

Warning: discussion of rape in myth upcoming

You may recall that in several fragments of the myth, the reason Tefnut leaves in anger is that She has been raped by Her son Geb. Isis, too, suffers rape by Her son Horus. A stele from the Middle Kingdom refers to Horus violating Isis while He “inclined His heart toward Her”(!?!). From the Harris Magical Papyrus, we have this heart-rending account of Isis’ reaction:

Isis is weary on the water; Isis lifts Herself on the water; Her tears fall into the water. See, Horus violates his mother Isis and Her tears fall into the water.

Harris Magical Papyrus, VIII, 9-10

In Koptos, where Min has the epithet Bull of His Mother and is the consort of Isis, the God eventually came to be assimilated with Horus—again sexually pairing Isis and Horus. So much so, that They formed the very unusual cross-sex combination form of Isis-Horus. In a papyrus from the Ramesseum collection, another falcon God, Hemen, a form of Horus, has sex with Isis and impregnates Nephthys with a daughter, and we again have reason to think this was not consensual. Of course the Goddess is angry.

Even in Plutarch’s rendition of the story of Isis and Osiris, Isis displays anger. As Isis is bringing Osiris’ body back to Egypt from Byblos by ship, the wind makes for rough sailing, so Isis dried up the river with an angry look. When She stopped to mourn Osiris, a prince of Byblos who had accompanied Her, became unwisely curious and observed Her in Her grief. She turned a terrible gaze upon him and he died instantly.

In Demotic (late Egyptian), we find a term hyt, that would be pronounced something like khyt, which could mean anything from divine inspiration and ecstasy to doom, fury, or curse. Interestingly, it was usually “cast” on or against someone or something—just as heka, magic, was (and is) cast. A graffito from Isis’ temple at Philae says that “the hyt of Isis is upon any man who will read these writings.” The person had written their name on the temple and was calling down the hyt of Isis on anyone who might remove the writing. A graffito at Aswan makes this clearer:

The hyt of Isis the Great, Chief of the Multitude/Army is upon every man on earth who will read these writings. Do not let [him] attack [the writings], to not let him disparage the writings. Every man on earth who will find these writings and erase or disparage the writings, Isis the Great, Chief of the Multitude/Army will decrease his lifetime because of it, while every man who will give praise and respond regarding them, [he will be praised(?)] before Isis the Great, the Great Goddess.”

Graffito Aswan 13, ll. 6-13; Appendix, no. 2, in Robert Ritner’s “An Eternal Curse upon the Reader of These Lines”

From Saqqara, a Demotic inscription forebodingly says that, “the hyt of Isis is upon you.” While Isis is not the only Deity having hyt (most did), we can at least see the fearsome power of Isis’ fury or curse. From the later Greek Magical Papyri, we still find a fierce Isis Who is called upon in an erotic spell of compulsion:

For Isis raised up a loud cry, and the world was thrown into confusion. She tosses and turns on her holy bed and its bonds and those of the daimon world are smashed to pieces because of the enmity and impiety of her, [name of the woman who does not desire the spell caster] whom [name of her mother] bore.

PGM XXXVI, 134-160

We’ve not come to the end of our exploration of Isis as a Wandering-Distant-Returning Goddess…but this post is long enough for now. So we’ll take it up again next time to see what else there might be to be seen.

For now, we know that Isis has a fierce lioness form, that She has reason to be angry in a manner similar to at least some of our Wandering Goddesses, and that, in Lower Egypt—around Her temple at Isiopolis—this myth was not only particularly important, prevalent, and widespread, but most of the Goddesses participated in some version of the myth in one way or another.