If so, how did that happen?

Did you do a specific ritual? Did it slowly gain its living quality over time?

Following the inspirations of ancient Egyptian cult, for me, the ones that are alive are so because of ritual. I’ve used versions of “Enlivening the Divine Image” from Isis Magic on several of them. But my main image—my BIG Isis—was enlivened long before Isis Magic existed.

To enliven Her, I invited a circle of friends to come over for an Isis birthday party. There was ritual around everything, of course, but the main event was that each participant cradled the image in their arms, as if holding a baby, and breathed their living breath into the sacred image…then passed Her to the next person. And it worked; She has been quite lively ever since.

But what exactly do I mean by “is alive,” anyway?

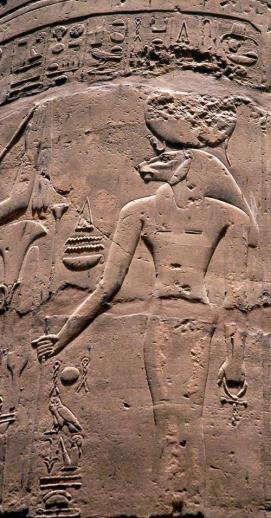

Let me give you an example. Several years ago, one of the traveling Egyptian museum shows came to our local museum and a group of us went. Of course, there were many wonderful things. But one image—smallish, broken, a head of Sakhmet in yellow alabaster—hummed with magical power. I felt Something in its presence. Mind you, not everything in the show felt like that. But this piece did. I think what I felt was the magic of the ritual that had “opened the mouth and eyes” of this sacred image of Sakhmet so that something of the Goddess was still within the image. The priests who worked that rite, those guys were good. This Sakhmet had power; it had life.

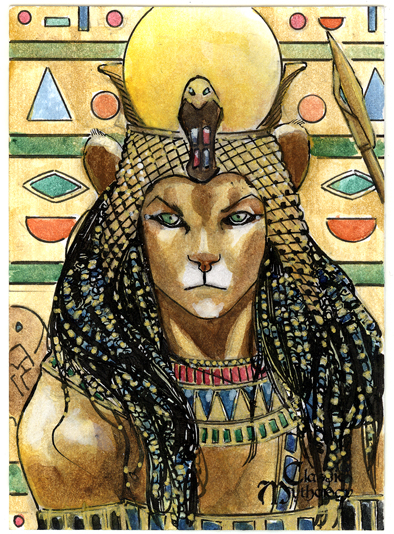

That’s what I want from my sacred images of Isis, too. When someone visits my Isis shrine, I hope they feel Something. A little buzz. A little hum. A little magic that says, “yes, I’m here.”

From the very start of the artistic process of making such a sacred image, the ancient Egyptians knew they were creating something that would be alive. Sculptors sometimes referred to their work as “giving birth.”

We are used to thinking of Egyptian statuary are gargantuan. But the main cult image in each temple—the one kept in the holy of holies and cared for each day—was likely no more than about a foot in height for anthropomorphic images. We know this due to the size of the shrines that enclosed these images. So this means that the size of the images many of us have on our own home altars are very much in harmony with the most important Egyptian temple images. I like that. A lot.

The oldest texts we have that provide information on what the ancients thought about their divine images come from the New Kingdom (1570-1069 BCE), but the ideas in them are likely much older. We find this information in ritual texts for the Daily Ritual, which cared for and fed the Deity and the Opening of the Mouth rite used to enliven the images, as well as some additional temple texts that mention the relationship between the Deities and Their images.

At core, what these texts make apparent is that some part of the essence of the Deity was considered to be alive in the sacred image. In the Daily Ritual, the sacred image is awakened, clothed, praised, and anointed as a living being. Each step in the ritual re-enlivens the statue each time the ritual is performed. Toward the end of the rite, the priest can finally say to the Deity in the image, “oh living ba who smites His enemies, Your ba is with You and Your sekhem is with You.” In this case, the ba of the Deity is Their manifestation (ba also has connotations of power) and sekhem is the word for power. The priest then says that he, too, is a ba and embraces the sacred image.

So at this point, the ba of the Deity is in the image. Ba is a complicated term and I won’t go into all its complications here. (Besides, I’m still learning about some of them.) For our purposes here, we can think of the ba of a Deity as Their Presence or Manifestation. In this way, the sacred image of the Deity IS the outward manifestation of the Deity. But that’s not all that it is. For we have other texts that tell us that the ba of the Deity swoops down like a great hawk to alight upon the image and indwell it.

But back to the Daily Ritual…

Next, food is presented and now the emphasis shifts to the ka of the Deity. The ritual says that Ma’et embraces the Deity “so that your ka will exist through Her.” The simplest definition for ka is “vital essence;” it’s the difference between alive and dead. And since I am, at this moment, into simplification, we’ll let that do for now.

The hieroglyph for the word ka is two upraised arms, perhaps intended to be read as an embrace. For it is through an embrace that ka may be passed, for example, from Atum to His children Shu and Tefnut to protect Them and give Them Their kas. The royal ka—the ancestral power that makes the pharaoh a pharaoh—is passed by an embrace from the old king as Osiris to his heir as Horus.

So we have two aspects of the Deity present in the sacred image during the Daily Rituals: ba and ka. The ba is the Presence and the ka is Life. It is through the ka that the Deity Who is alive in the sacred image receives offerings. You can read more about that here.

These sacred images were taken out in procession during certain festivals. On such occasions, the Deity would also be present in the image—present enough to give oracular responses, and we even have one instance of a man claiming that he was cured of blindness during such a procession. Unfortunately, we don’t have texts of any of the rituals that might re-enliven or “charge up” the image before going out, but we know they existed because the library at Edfu was supposed to contain a book of “all ritual relating to the exodus of the God from His temple on feast days.”

From another temple text, we know that the Opening of the Mouth ritual was performed on statues. The full name of the text is “Performing the Opening of the Mouth in the workshop for the statue (tut) of (Name of person or Deity).” The key part of that ritual was known as netjerty, when the mouth of the image was touched with the adze, a specific craftsman’s tool. Netjerty is formed from the root Netjer (also Nutjer, Neter)—Deity—so we can understand that this part of the rite was a god-ifying part. Much of the rest of the ritual is very similar to the Daily Ritual and its magic, with both ba and ka present.

Other than these references in the Daily Ritual and Opening of the Mouth, there are a few scattered references about the relationship between Deity and image. In the Hibis temple of Amun-Re, all the other Deities are considered aspects of Him as Creator. And, as Creator, He is also the one Who creates His own image. He made it “according to His desire, He having graced it with the grace of His breath…” In the Daily Ritual text that we have for Amun, He is said to be “the tut Who made Their [all the Deities] kas.”

In several similar passages, the creation of the sacred image is attributed to the Deity Who’s image it was. This reminds me of why all the books of Egypt could be said to have been written by Thoth: the scribe, in the act of writing, is in the Godform of Thoth, so the book is written by Thoth. Perhaps the sculptors and artists were supposed to be in the Deityform of the Deity they were sculpting, too. I am imagining an artist, in the Goddessform of Isis, crafting Her image by channeling inspiration from Her.

In what is known as the Memphite Theology, Ptah the Craftsman is the Creator and He creates the bodies—statues—of all the Deities according to Their desire, so that They willingly “enter into” Their bodies and Their kas are satisfied.

At Isis’ temple at Philae, a text says that Isis’ son Horus is the one who established all the temples and made all the sacred images. Horus and Hathor were known to “go out as Their statues” during one of Their festivals. Edfu temple also has passages that say the Deities “unite with Their bas in the horizon—the akhet, that most liminal of liminal places and a very reasonable place to work this transitional magic.

From these and similar clues, we can be sure that a Deity’s ba and ka were understood to be present in Their sacred images. What’s more, Their presence in one temple neither precluded nor diminished Their presence or power in another. Both ka and ba are in divinely infinite supply.

Thus Isis can be alive and present in my shine, on your altar, and on the altars and in the shrines of all those who love Her.

May She bless and be alive in your sacred image always.