Last time, we wondered how it was that the ancient Egyptians and Greeks could see a harmony, or even an equivalence, between Isis and Hekate. So, as promised, let’s look at some of the correspondences between these two Goddesses so we can understand a bit better what they were thinking.

Goddesses of Magic

Let’s start with the most obvious one: magic. Isis is arguably the most powerful Egyptian Goddess of Magic, or heka in Egyptian (later, hik in Coptic). In Egypt, heka is the power that underlies and empowers all of Creation. So naturally, all the Egyptian Deities have the power of heka. Yet, as time went on, it was Isis and Thoth Who stood out as Goddess and God of Magic, both for the strength of Their magical powers and the depth of Their magical knowledge.

Hekate is the Hellenic Goddess of magic and witchcraft. Sometimes, Hekate’s magic has a bit of a darker flavor than that of Isis for She is often associated with pharmaka, magical arts and spells, but which can also be drugs, both beneficial and poisonous.

Both Goddesses are also known to teach the magical arts to Their devotees.

While traveling the wilds of the internet, you may have seen some people saying that Hekate’s name may be derived from a.) the Egyptian Frog Goddess of Fertility Heqet or Heket, or b.) from the Egyptian word for magic, heka. For the connection with Heqet, we have this speculation from Martin Bernal (author of the Black Athena series):

“The crone goddess Hekate [note: Hekate was never a crone] was central to the Eleusinian Mysteries, whose name, like that of nearly all Greek divinities, has no Indo-European etymology. Her name almost certainly derives from the Egyptian frog goddess Hkt or Hqt. Both were versed in magic—ḥk3 in Egyptian—and fertility. There is, to my knowledge, only one connection drawn between Hekate and frogs. This comes in Aristophanes’ parody of the Eleusinian initiation, “The Frogs,” where the chorus condemns those who defile Hekate’s shrine. The chorus of frogs appears while the travellers are crossing to Hades on Kharon’s ferry. In the Egyptian Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom, Sokar’s ferry to the Underworld is reported to have “her bailers . . . [as] the frog goddess Hqt at the mouth of her lake.” (Martin Bernal, “Egyptians in the Hellenistic Woodpile” in Ptolemy Philadelphus II and His World)

While Bernal has been heavily criticized for making these kinds of leaps (e.g. “almost certainly”), I do find his work very valuable in helping trace connections between the you-simply-couldn’t-ignore-it ancient Egyptian civilization and that of the ancient Greeks. Nevertheless, this one looks like quite the stretch to me. The frog connection is pretty tenuous and Heqet was never well known enough outside of Egypt to be that influential. A better correspondence might be between Isis’ title of Hekaiet, “Magician,” and Hekate, but I can’t offer further speculation on that as I’m no linguist.

Universal Goddesses

Both Goddesses are powerful in every sphere of life, on every level of reality. Isis is said to be queen of earth, heaven, and underworld. Hesiod, in the Theogony tells us that Hekate has power in earth, sea, and sky. And while Hesiod doesn’t specifically list the underworld as one of Hekate’s realms, it is clear that Her connections with the dead make Her an underworld Goddess, too. Both Isis and Hekate serve as psychopomps. Hekate guides Persephone back to the land of the living and Isis initiates the newly dead into their new lives.

Protective Goddesses

With Her widespread wings, Isis is the protective Goddess par excellence. She not only protects Her child Horus, Her husband Osiris, and the land of Egypt, but each of Her devotees as well. With Her magical power, Hekate is also a protective Goddess, Her image placed before each household to keep its inhabitants safe.

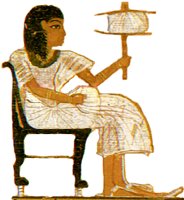

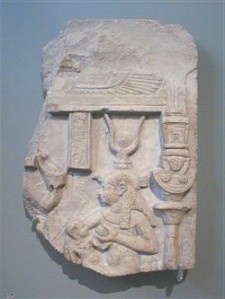

Child Nurturing Goddesses

Both Isis and Hekate bear the Greek epithet Kourotrophos, “Child Nurturing.” Of course we see Isis nurturing Her own child, Horus, but human children were often placed under Her protection as were young people in general. People often made offering to Hekate asking Her to protect their young as well.

Goddesses of Many Names

With Isis’ astonishing number of syncretizations with Goddesses (and some Gods) both inside and outside of Egypt, as well as Her power in every area of life, She truly earned the title of Myriad-Named. Yet Hekate is also many named and connected with many other Goddesses. I’m going to give Isis the edge in this category, however, because the extent to which this happened with Her was and is simply unprecedented.

Fiery Goddesses

Hekate is strongly associated with burning torches while Isis is a fire-spitting Uraeus Goddess and burning Eye of the Sun.

Goddesses of the Moon

In this category, I’ll give Hekate the edge. With Her prominent triplicity, Hekate has an easy connection with the triple visible phases of the moon, as well as Her association with the mysteries of the dark moon and the offerings of Hekate’s suppers. But Isis is not without Her lunar connections. In fact, many modern people first think of Isis as a Moon Goddess. In later periods of Her worship, She was indeed associated with the moon, particularly when Egypt came under Greek rule. For the whole story on Isis as a Moon Goddess, go here.

Savior Goddesses

Both Isis and Hekate are specifically called Savior (Soteira in Greek). Isis was called Soteira as She became universalized in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Hekate became Soteira through Her role in the Chaldean Oracles as the World Soul. Many of us are used to thinking of “salvation” in Christian terms—believe, and the Deity will forgive your sins, saving your soul for eternal life. But the ancients had a broader definition. Savior Deities could save you from earthly troubles as well as caring for your soul in the afterlife. The Savior Deities also saved people from their fear of death. By being initiated into knowledge of the afterlife and being assured of the favor of their Goddess, people could face their end of life in peace.

Scary Goddesses

With Her connection to the dead, especially the restless and unhappy dead who can accompany Her, Hekate can be a frightening Goddess. She might be called upon in necromantic rites—raising the dead for information—which is naturally unsettling. Frightening aspects of the Goddess are called upon in some of the magical spells we have left to us. The Goddess Herself might appear in a frightening form with rattling chains and animalistic moans and roars. But Isis is never scary, is She? Welp. Yes, She can be. Isis’ own connections with Mysteries, death, and the underworld could make Her a Dread Goddess, too. After all, if She can create, She can destroy. The Pyramid Texts include a passage that says, “If Isis comes to you in Her evil coming, do not open your arms to Her.” Other tales tell of Isis killing a prince with an angry glance and that a rash man who tried to sneak into Her sanctuary without an invitation expired on the spot.

Animals of the Goddesses

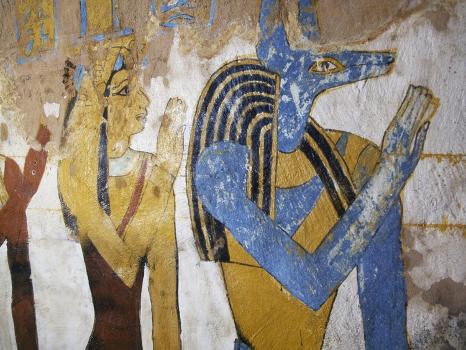

The Goddesses also share some connections though the animals that are sacred to both. For instance, both are associated with dogs. Hekate has Her accompanying hounds, whose howls proceed Her arrival. Isis is closely connected with canine Anubis, sometimes even as His foster mother. She is also associated with “the dog star,” Sirius. In one of Her aretalogies, Isis says of Herself, “I am She who rises in the Dog Star.” Both Goddesses are connected with snakes. Hekatean imagery often includes serpents, while Isis Herself is a Cobra Goddess.

Hekate is connected with bulls and cows, which were/are considered lunar animals due to the crescent-like horns they bear. Hekate Herself sometimes has the head of a bull as one of Her three animal-form heads. In later periods, Isis shares the crescent-horns-moon association, but She is also a Cow Goddess in Her own right, from very early on. She also is assimilated with Hathor, the most prominent Egyptian Cow Goddess. Like many Asia Minor Goddesses, Hekate is often associated with lions. Sometimes, one of Her animal-form heads is that of a lioness. Isis IS a Lioness Goddess. As the Eye of the Sun, She also takes the form of a fierce lioness and we have a number of portrayals of Isis with the head of a lion, looking quite a bit like Sakhmet. And yes, you guessed it, She is often syncretized with Lioness Sakhmet.

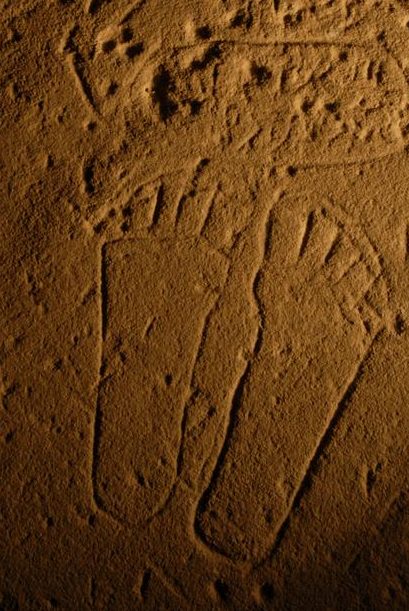

Temple Footprints for the Goddesses

There is one last correspondence I want to mention, but not dwell on. That’s because it’s interesting enough to deserve it’s own blog post. One of the things pilgrims traveling to temples might do is leave a certain type of graffito scratched into the stones of the temple. The graffito was a foot or pair of feet, often along with a written dedication. They were meant to symbolize the person permanently standing at the temple. We find these pilgrim feet at a number of Isis temples and shrines as well as at Hekate’s temple at Lagina in modern Turkey. Click for info on the sacred graffiti at Isis’ temple at Philae.

No doubt there are other connections that can be made between these two Great Goddesses. But I think this is sufficient for us to understand why the ancient Egyptians and Greeks might have been inclined to associate Them.

So, are Isis and Hekate “the same?” No, not exactly. But are They connected? Yes, They are indeed.