“O, Isis, Great of Magic, deliver me from all bad, evil, and typhonic things…” —Ebers Papyrus, 1500 BCE

One of Isis’ most powerful epithets is “Great of Magic,” which you may also see translated as Great One of Magic, Great Sorceress, or Great Enchantress. In Egyptian, it is Weret Hekau or Werethekau. (“Wer” is “great” and “et” is the feminine ending. “Hekau” is the plural of “magic,” so you could also translate it as Great of Magics.)

Isis is not the only Goddess Who is called Great of Magic. Indeed, many of the Great Goddesses bear that epithet: Hathor, Sakhmet, Mut, Wadjet, among others. Gods are also Great of Magic, notably Set in the Pyramid Texts.

There is also a Werethekau Who is a Goddess in Her own right, rather than an epithet. As so many Deities were, She was associated with the king, and especially during his coronation. There had been some doubt among Egyptologists about whether Werethekau was indeed a separate Goddess. But recently, Ahmed Mekawy Ouda of Cairo University has been doing a lot of work tracking Her down. He’s gathered references to a priesthood and temples for Her that seem quite clear. More on all that in a moment.

In addition to the Great of Magic Deities, there are objects called Great of Magic, especially objects associated with the king, such as the royal crowns. In the Pyramid Texts, the king goes before a very personified Red Crown:

“The Akhet’s door has been opened, its doorbolts have drawn back. He has come to you, Red Crown; he has come to you, Fiery One; he has come to you, Great One; he has come to you, Great of Magic—clean for you and fearful because of you . . . He has come to you, Great of Magic: he is Horus, encircled by the aegis of his eye, the Great of Magic.”

—Pyramid Texts of Unis, 153

Some amulets, including a vulture amulet, a cobra amulet, and, as in the example above, the Eye of Horus amulet are also called Great of Magic. So is the adze used in the Opening of the Mouth ceremony.

With all this great magic going for him or her, the king or queen becomes Great of Magic, too. King Pepi Neferkare is told, “Horus has made your magic great in your identity of Great of Magic” (Pyramid Texts of Pepi, 315). Queen Neith is told, “Horus has made your magic great in your identity of Great of Magic. You are the Great God” (Pyramid Texts of Neith, 225).

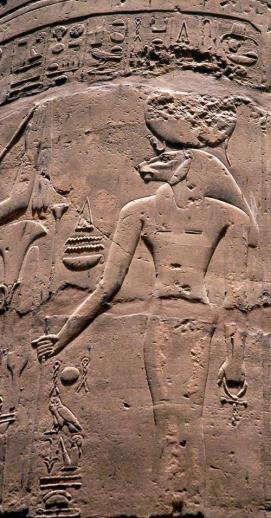

I wonder whether there might be some primordial connection between the Great of Magic royal crowns and the Great of Magic royal throne—Who is Iset, the Goddess Throne. There is a votive stele that shows Werethekau and gives Her the epithet Lady of the Throne of the Two Lands. Perhaps we can understand the accouterments of kingship as personified extensions of the Power, Divinity, and Magic of the Living Great Goddesses, which were empowered by Them in order to bestow upon the king his own power, divinity, and magic.

The magic of the crowns is enhanced by the protective uraeus serpents often shown upon them. They’re not just snakes, of course; They’re Goddesses. Most often, the Uraeus Goddesses are Wadjet and Nekhbet or Isis and Nephthys, representing Lower and Upper Egypt. But Werethekau is a Uraeus Goddess, too. The uraei are also known as “Eyes” due to the similarity between the Egyptian word for “eye” (iret) and the word for “the doer” (iret)—because it is the Eyes of the Deities that are the Divine Powers which go out to do things. (Very similar to the active and feminine Shakti power in Hinduism.)

The Pyramid Texts of King Merenre associate the Eyes with the crowns:

“You are the god who controls all the Gods, for the Eye has emerged in your head as the Nile Valley Great-of-Magic Crown, the Eye has emerged in your head as the Delta Great-of-Magic Crown, Horus has followed you and desired you, and you are apparent as the Dual King, in control of all the Gods and Their kas as well.”

—Pyramid Texts of Merenre, 52

The Uraeus Goddesses or Eyes are powerful, holy cobras Who emit Light and spit Fire against the enemies of the king and the Deities. Learn more about Isis as Uraeus Goddess here.

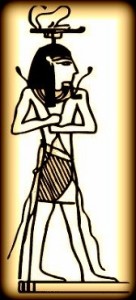

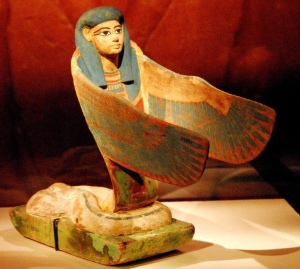

When Werethekau is an independent Goddess, She may have the body of a woman and head of a cobra, be in full cobra form, and we even have a few instances of the Goddess in full human form. Among Tutankhamun’s grave goods is a figure of Werethekau with a human head and cobra body nursing a child Tut.

She also has a lioness form. We know of a lionine Isis-Werethekau from the hypostyle hall at Karnak. A number of the Goddesses with a feline form—Sakhmet, Mut, Pakhet—were also known as Great of Magic, so we can understand that powerful magic has not only a protective and nurturing side, but also a fierce and raging one. Which seems about right if you ask me; magic can be very positive and healing or, if used unwisely, a real mess.

So far, I haven’t tracked down the oldest reference to Isis as Great of Magic. Since She has always been a Goddess of great magical power, the association is ancient. Perhaps it has always been. Perhaps there’s something to my guess about The Great-of-Magic Throne. Or perhaps Professor Ouda will come to my rescue if I can ever get a copy of his thesis about this.

In Ouda’s article outlining some of the references to Werethekau’s priesthood and temples, several of the extant references to Werethekau also tie-in Isis and Her Divine family.

For instance, on a stele of a chantress of Isis, the chantress is shown playing the sistrum and adoring Isis-Werethekau. The inscription reads, “adoring Werethekau, may They [Isis and Werethekau?] give life and health to the ka of the chantress of Isis, Ta-mut-neferet (Isis the Beautiful Mother).” In fact, on the less-than-a-dozen votive stele we have and on which Werethekau is named or depicted, many of them are stele for people who served Isis in some priestly capacity; they may have also served Osiris and Horus, too.

Ta-mut-neferet holds the hand of a man identified as “the servant of Osiris.” Another stele calls Werethekau “Lady of the Palace” and is dedicated by a chantress of Osiris, Horus, and Isis. A man who was Second God’s Servant of Osiris, God’s Servant of Horus, and God’s Servant of Isis was also God’s Servant of Werethekau, Lady of the Palace.

Ouda also notes that Lady of the Palace may be Werethekau’s most common epithet. That is quite interesting in light of the fact that Lady of the Palace (or House or Temple) is the very meaning of Nephthys’ name. (Learn more about that here.) And of course, She, too, is called Great of Magic. Together, Isis and Nephthys are the Two Uraeus Goddesses and the Two Greats of Magic.

So if the question is, “is Werethekau an independent Goddess, a personified object, or an epithet of other Deities?”, the answer is, “yes”. With the beautiful and, to my mind, admirable fluidity of the Egyptian Divine, She is all these things…and most especially, a powerful aspect of Isis, the Great Enchantress.