Part 3

Let’s finish up our exploration of Isis as a Wandering Goddess by looking at some additional ways Isis’ story fits in with the myth of the Wandering/Distant/Returning Goddess. Last time we saw how Isis’ lioness form and the raped-Goddess theme fit in with other Wandering and Distant Goddesses, as well as how prevalent that myth was in the Delta—the place where Isis’ worship most likely originated.

So let’s see what else we can find out.

Eye of Re

In addition to being fierce and protective Lioness Goddesses, our Wandering Goddesses are also fierce and protective Eye Goddesses. Usually, They are Solar Eyes—Daughters of Re—hence Their fiery nature—though we saw that the Lioness Goddess Mehyt may be associated with the Udjat Eye, the full Lunar Eye, which in turn connects Her with the ever-so-famous Eye of Horus, son of Isis.

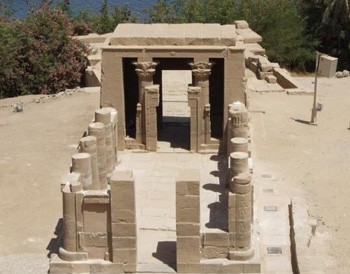

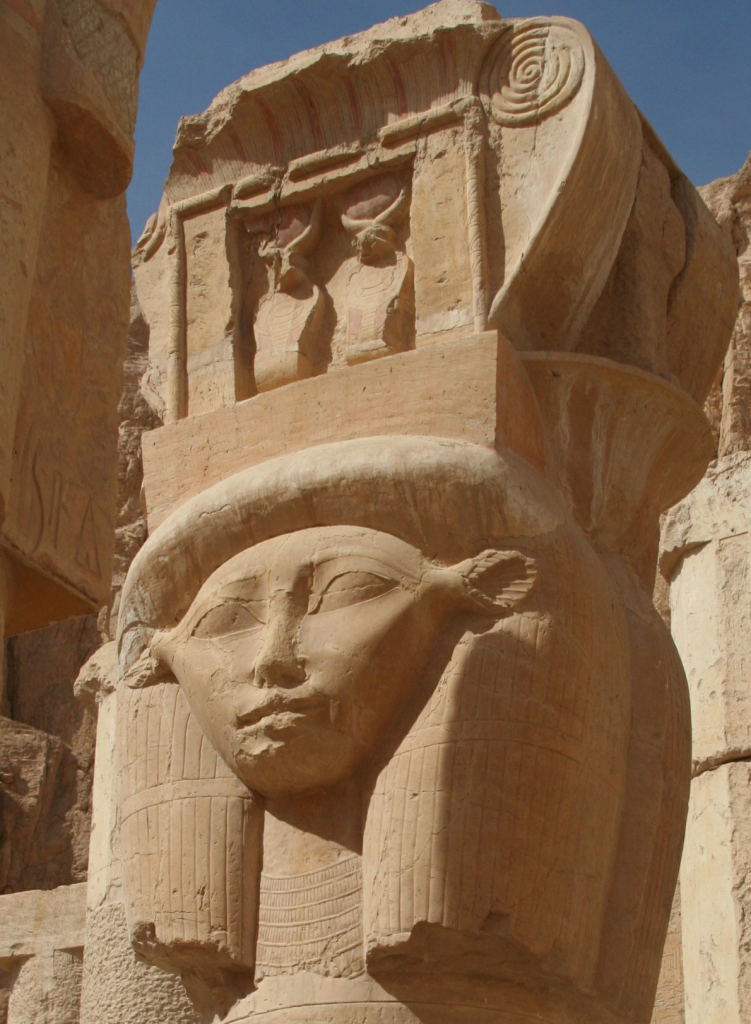

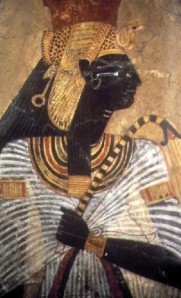

Isis is Herself a Divine Eye and Daughter of the Sun God Re. She is said to “emerge” from Re or “come forth” from His body. At Her Philae temple, inscriptions say that She “appears” as the Eye of Re. (On the other hand, as a Primordial Goddess, Isis is also said to give birth to Re, so there’s that.) Isis is called Re’et, the Female Re…indeed, at Denderah She is called “the Re’et of Re’ets,” that is, “Sun Goddess of Sun Goddesses,” and She is also Queen of the Re’et Goddesses. She is the Solar Eye, “the right eye of He Who shines like gold” and She is the solar disk, the Aten Itself. Hathor and Isis are the only Goddesses Who have the distinction of being identified as the solar disk itself. At Denderah, Isis is Re’et “in the dual course of the sun and the moon,” and so She encompasses both Solar and Lunar Eyes.

The Fiery Goddess strikes fear in the heart of Her, and Re’s, enemies. Her power can cause death “in this vigorous form” and She describes Herself as “She who triumphs, the companion of Re.” As the Sacred Eye, the Goddess coils as a uraeus serpent and third eye upon the Sun God’s brow, protecting Him and fighting an ongoing cosmic battle against His great opponent, the destructive Serpent Apop (Gr. Apophis). Inscriptions from Philae call Isis “Neseret-serpent on the head of Horus-Re, Eye of Re, the Unique Goddess, Uraeus” and “Eye of Re Who has No Equal in Heaven and on Earth.”

In addition to being a Divine Eye, we can also understand Isis as having particularly keen sight due to Her sharp raptor’s eyes. Her most prominent sacred bird is the kite hawk, whose sky-high viewpoint gives it an advantage in being able to see far distances, which could easily lead to the conclusion that it was All Seeing. In later periods of Her worship, Isis was invoked not only as “all-seeing,” but “many-eyed.”

Isidorus’ Faiyum hymns to the Goddess describe Her as gazing down on the activities of humanity and noting the individual virtues of human beings. Yet the glance of Isis’ sharp eye can have dire consequences for those who oppose Her. When the Ennead of the Gods is arguing over whether Horus or Set should receive Osiris’ throne, the Deities back down in the face of the anger and flashing eyes of Isis.

The Goddess Leaves the Premises

The next few pieces of our puzzle, I admit, are not as strong as the argument to date. We just don’t have a surviving Isis myth that’s close to Tefnut’s or Hathor/Sakhmet’s angry departure and joyful return. My guess is that Isis became so strongly associated with the Osirian myth cycle—and there were so many other Goddesses associated with the Wandering Goddess cycle—that there simply wasn’t a need for people to retain that particular myth—if there originally was one, as I think there was—in relation to Isis.

As Isis began to break away from the Goddess pack, so to speak, and Her worship spread not only throughout Egypt, but into the entire Mediterranean region and beyond, there was less and less reason to include that theme in Her worship. Instead, the very human, heart-touching emotionalism, tragedy, and eventual triumph of the Isis-Osiris-Horus myth took over…even as She was becoming, more and more, the Goddess of 10,000 Names.

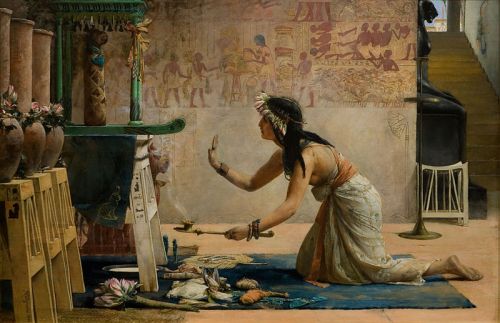

And yet, Isis does wander. She wanders throughout the length and depth of Egypt searching for the pieces of Her Beloved’s body. She creates shrines in the major cities and towns of Egypt, so that Her story is known by all. The ubiquity of the Isis-Osiris myth was so prevalent that the historian Herodotus, in the 5th century BCE, had the impression that Isis and Osiris were the only two Deities universally worshiped in Egypt. Not only that, but we can imagine that Isis’ wandering is filled with grief and mourning, yes, but also with anger. If you have ever lost someone suddenly, you will understand, on a gut level, that anger is a very familiar part of mourning.

Is Induced to Return

Rather than being coaxed into returning home, however, Isis is more self-directed. She returns when Her task of gathering Osiris is complete and She has guided His resurrection and transformation into Lord of the Dead. Her concerns at home now turn to ensuring Horus takes His rightful place as king. And here again we see Her demonstrate the fiery power and righteous anger of the Divine Eye. Remember what we saw above regarding the Ennead backing down in the face of Her anger.

Is Pacified (and Goes on a Boat Ride)

Backing down and admitting that Horus should indeed be king, the Ennead pacifies Isis. Ah, so Our Lady did need a bit of placation after all. What’s more, at Hathor’s Denderah temple, where the two Goddesses are so, so close, we even find that Isis needed an isheru to cool Her off.

At Denderah, Hathor and Isis often mirror each other. In the main temple, we see Hathor on Her throne on one wall and Isis on another. Beneath Hathor’s throne we see 16 vases of Inundation water, one vase for each cubit of the ideal height for the Nile flood. The king offers Her a jar of Primordial Water, while Her son Ihy plays the sistrum and rattles the menat to sooth Her anger. On another wall in the same room, we find Isis enthroned. Beneath and around Her throne are the wavy lines that indicate water in a basin shaped roughly like an isheru. The inscription identifies it as precisely that by telling us that, “Her isheru lake is all around Her.”

This same scene, the two seated Goddesses with 16 vases beneath Hathor’s throne and an isheru surrounding that of Isis, is also found in Denderah’s so-called Chapel of Purification, the Per-Nu. And yet again, the same scene of Isis alone is found on another wall in a different room of the temple. As before, the enthroned Isis is seated over an isheru-shaped basin. The inscription reads, “Isis the Great . . . is seated/pacified in the isheru that is all around Her, Who crosses the lake within Her barque.” The inscriptions go on to describe Isis’ traveling on the isheru as a meeting with Her father Nun and tell us that He enfolds Her in His arms. Both Isis and Hathor are connected with the Inundation and the Primordial Waters. The Waters are offered by the king to Hathor since She regulates the ideal Inundation, while Isis, Who brings the Inundation, is embraced by Her father Who is said to be the primordial Watery Abyss Himself.

The Goddesses’ ritual travel by boat upon the isheru is known to Egyptologists as a navigation. (At Denderah, there were 9 navigations, by the way: one for each place the Goddess stopped on Her way back from Nubia.)

We might remember that Isis, too, has a rather famous navigation: the Navigium Isidis (the “ship of Isis” or “sailing of Isis”). I’m still trying to confirm the Egyptian word that was used for the “navigation” in the Hathor-Isis festival. There is an Egyptian word, khenet, which is related to other words having to do with boats, sailors, and navigation—as well as a festival of Osiris that featured a procession of boats—but I’m not sure whether the same word was used for the navigation of Isis and Hathor on the isheru.

Nevertheless, it is clear that at Denderah one of the things the Return of the Goddess was about was the return of the waters of the Inundation that would bring food and prosperity to Egypt. In addition, the rising river made the Nile more navigable for a wider variety of boats and ships. Just before the flood was the time of the river’s lowest, most-difficult-to-travel water levels. The Navigium Isidis (Gk: Ta Ploiaphesia; the Launching [of the Ship of Isis]), while not concerned with the water level or Inundation of the Nile, was concerned with the navigability of the Mediterranean Sea that would mark the start of the shipping season in spring.

Then Festival Ensues

We now come to the final element in the Wandering Goddess myth: Her joyful return and the Festival of Drunkenness. We have already seen evidence of such festivals for Mut, Tefnut, Bastet, Nehemant, and of course, Hathor. And I’m sure that, at Denderah, with the closeness of the Goddesses, Isis devotees would have participated with Hathor devotees during the festivals held there. There certainly were joyous festivals for Isis—She is, after all, called “the Festive Goddess.” Often, these were related to the conception and birth of Horus and the birthdays of Isis and Her siblings during the epagomenal days. What’s more, She is known as a joyful Goddess; temple inscriptions call Her the Queen of Joy, Lady of Rejoicing, and Lady of Jubilation. Deities and human beings rejoice when They/they see Her. Isis is called She Whose Heart is Open and Her joy is likened to the beauty of the full moon.

Still, we don’t have solid evidence of a full-fledged Festival of Drunkenness for Isis.

And yet.

There are these two little bits of graffiti from Her temple at Philae. They’re in bad shape. They’re from a late period. But one mentions a day of singing and drunkenness, the other notes a dedication to Hathor, a “house of greeting,” and “the place of drunkenness of the people.”

In fact, all of this makes sense. Philae was home to a temple of Hathor—just as Denderah included a temple of Isis. Philae was also Tefnut’s first stop on Her way back from Nubia.

It was at Philae that She changed from burning lioness to peaceful Goddess. So it may well be that—in that fluid way of Egyptian Goddesses and Their festivals—Isis-Hathor-Tefnut may have been celebrated with a Festival of Drunkenness at Philae, too. Since there is no temple calendar carved on the walls at Philae, we can’t be sure, but perhaps we will learn more from other discoveries as time goes on.

So, there you have it. It may have been that Our Lady Isis participated in both of the great mythic themes of ancient Egypt: the Isis & Osiris story as well as the myths of the Wandering/Distant/Returning Goddess.