I’ve done some more reading and some more meditation and I want to come back to neheh and djet. Why? Because I am very inspired by a 2022 work by Egyptologist Steven Gregory on the subject.

Unless you’re super geeky on this subject like me, I don’t think you’ll want to read all his arguments for how he thinks neheh and djet should be defined and translated.* (Translating is the trickier part, tbh.) So I’ll summarize and then we can discover some things we might do with these insights.

As we saw last time, Egyptologists have tried translating these two Egyptian concepts in a variety of ways, all of which, I think, add to our understanding. Their interpretations usually have to do with a repetitive time cycle for neheh and a perfected and unchanging time cycle for djet. But rather frequently, when translating the ancient texts, Egyptologists will translate the two terms as if they were synonyms. That’s when we get translations of neheh djet as “forever and ever.” This is Gregory’s big bugaboo.

He argues, persuasively as far as I am concerned, that they are very much not synonyms and that we miss an important part of what the texts are telling us if we so translate. In the book, he takes a while to get to his point because he gives lots of examples, but the point itself is actually fairly easy to home in on. It is simply this: that neheh is physical and temporal, like the cycles of sun and moon in our “real world;” djet is metaphysical and atemporal. In other words, they are not really types of time (though they are sort of), but conditions. Neheh is the condition of the existing world. It is imperfect and changing, providing for natural cycles and regeneration. Djet is the condition of the ideal world; it is the state of the Deities. Djet is outside of time. It is, or contains, the ideal Forms of everything.

And if that makes you think of Plato and his Forms/Ideas/Ideals, yes indeed, Gregory suggests that Plato may have been inspired by the ancient Egyptian concepts of neheh and djet. The Greek philosopher is, after all, said to have studied in Egypt.

If we were to apply those terms to Plato’s philosophy, neheh would be his world of appearances, which is a shadow of the more-real World of Forms. Djet is the realm of the Forms/Ideas/Ideals, which are “abstract, perfect, unchanging concepts or ideals that transcend time or space.”

As I said, I think all the translators’ translations are helpful in understanding these key concepts. And sometimes, thinking of them as variations on time is quite useful. But layering on Gregory’s physical-metaphysical definitions just opened the doors wider for me. It’s funny how sometimes a little thing like a new avenue for looking at things can blossom and unfold and burst into galaxies in your head. This was one of those for me. And it just reinforced for me how much the ancient Egyptian scribes and priests knew what the hell they were doing. They KNEW they were writing about different levels of reality. Always. Because our examples of this go back all the way to the earliest writings. In funerary texts, temple texts, and ritual documents of all kinds, they were very much aware of the different Worlds and they addressed those Worlds in their works, calling them out as neheh and djet. What’s more, thinking of djet as the metaphysical realm, we get additional hints as to how the ancient Egyptians may of conceived of the Divine realms.

I still do like the idea of neheh-time and djet-time, as well as neheh-eternity and djet-eternity, even though my guy Gregory doesn’t so much. But with his insights, we can now add new layers to our own definitions. We can think about the neheh-realm and the djet-realm—Neheh World and Djet World—so that we have levels or planes of reality as well as different dimensions of time and eternity. Of course, we’ve always known about the realness of the heavenly and underworlds in Egyptian thought, but adding the extra mystery of djet-time-eternity to it just adds to the complexity of Reality, which for me reveals a little bit more of what is true, what is right, what is Ma’et.

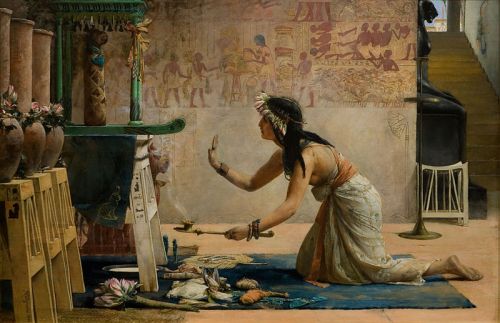

If you would like to experience these concepts for yourself, try the following visualization and meditation. This one focuses on djet, but you can do something similar for neheh.

Purify and consecrate yourself in any manner you wish. If you’d like an Isiac version, you could use the first part of this, up to “Entering.”

In your vision, imagine yourself in the Temple of Isis. It is night. The temple is illuminated by wall torches, burning in startling colors of blue and orange. As you enter in, you smell the smoke of incense, dark, sweet, and musky. You feel the cool stone floor on your bare feet. As your eyes adjust to the darkness, you begin to make out the designs of wall paintings. In the flickers of torchlight, their colors are muted. The low, rumbling sound of soft chanting comes to your ears. You hear Her name being chanted over and again with devotion, with love. Join in, if you wish.

Ahead there is a doorway, and beyond it, another. And another, and again. A long passageway stretches before you. Impossibly, it seems you can see into forever. A soft, deep voice whispers in your mind, “Enter the Chamber of Secrets.”

You enter the passageway, moving through each doorway. In a little while, the path begins to angle upward. Then you see a stairway that you somehow know will take you to the roof of the temple.

Walk up the stairs and you emerge on the temple roof. Look up. And you look into the infinite belly of Nuet, full of stars. Stars and space, moving slowly in their infinity, envelop you. Your eyes can see into the depths of space, opening, opening, opening. Your eyes, your heart, your mind, opening, opening, opening.

And when you let your attention fall back to the roof of the temple, you see the Boat of Millions of Years docked near the edge of the roof. It floats on darkness and stars. Thoth, the master of this vessel, motions you aboard. As you step upon the deck, the boat rocks and dips as if it were floating in water. You take your place, facing the prow, facing the night.

In a moment, the ship begins to move. First, slowly. Then faster. And faster. Moving upward into the depths of space and time. Starlight streaks by you. Your hair is blown back as the Boat of Millions of Years sails and sails.

Then suddenly, it stops.

The soft voice in your head, the one you know is the voice of Isis, says, “Call to Her.” And you do. You call to the Great Goddess Djet, asking Her to come to you, come to you.

Do this now.

In an unknown period of time, the Great Goddess Djet answers. “I am all around you and I am in you. The threads of My Magic knit you together. You are born from Me, but do not live in Me.” And you ask Her how you can better experience Her. She says, “Imagine yourself perfected.”

And you do. Allow as much time as you need for this thought experiment. What would you be like? Who would you be? How would you feel? How would you be?

When you are complete with this, thank the Goddess. The soft, deep voice of Isis speaks in your mind. “Come now,” She says. And you are once more aware of the Boat of Millions of Years. It once more begins to move, this time backwards. In time, you arrive at the roof of the Temple of Isis, thank Great Thoth, and disembark. Move down the stairs, through the many doorways. Thank Wise Isis and let your consciousness return to the here and now, to neheh.

*If you are super geeky and want to read the whole thing for yourself, get Tutankhamun Knew the Names of the Two Great Gods: dt and nhh as Fundamental Concepts of Pharaonic Idealology by Steven R. W. Gregory.