Part 2

A Mysterious Artifact

At about the time we first hear about the Mensa Isiaca, non-Egyptians were becoming increasingly fascinated with ancient Egypt. They wanted to discover what the hieroglyphs said. And because it had so many hieroglyphs, the Mensa Isiaca was one of the key sources for such early discovery.

One of earliest to take a specific interest in it was Lorenzo Pignoria, an Italian cleric, antiquarian, writer, and philosopher. In 1605, he published “An accurate explanation of the very Ancient Brazen Tablet, engraved with the Sacred Figures of the Egyptians.”

It includes a drawing of the Mensa, but apparently Pignoria was only able to identify a few of the figures and pronounced himself unable to fully unravel its secrets. Yet now a large-sized reproduction of the Mensa, in convenient paper form, was available to other researchers.

The Secrets of the Egyptians

It was Athanasius Kircher, a German Jesuit scholar and polymath, who really went to town on the Mensa. He believed it to be from the holy-of-holies of an Egyptian temple and to contain a wealth of mystical secrets.

Kircher’s personal studies spanned most of the arts and sciences of his day, from music to geology, as well as multiple languages, including Coptic. He correctly understood Coptic to be a late form of ancient Egyptian and produced a book on Coptic grammar.

While he was a devout Catholic and a biblical literalist, he also wholeheartedly embraced the Hermetic writings, no doubt influenced by Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola before him. He had a keen interest in ancient Egypt and considered Egypt to be the source of all ancient religion, from Greece and Rome to China and the Americas.

Thus, he wanted to understand ancient Egyptian religion because he believed it was humankind’s earliest and that there were underlying harmonies in all religions. Through later, better-documented religions, he believed he could extrapolate information about the Egyptian. According to Kircher, the theologies of Zoroaster, Orpheus, Pythagoras, Plato, Proclus, the Chaldeans, and Hebrew Qabalah all had their source in ancient Egypt. He was definitely of the “all the Gods are one God” school…with that one God (eventually) being the Holy Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

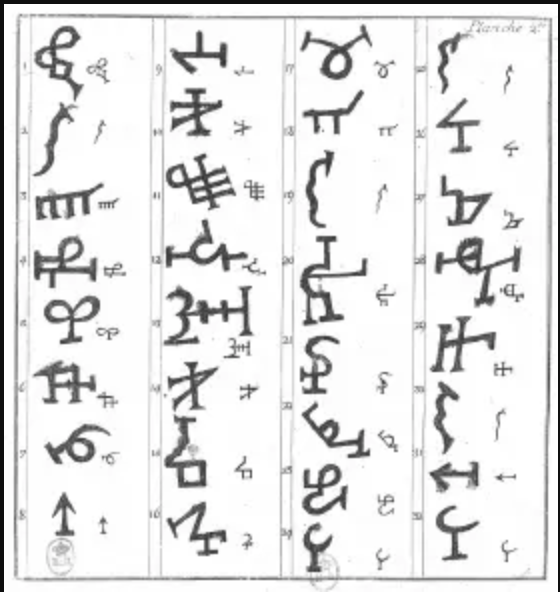

His key Egyptological work is Oedipus Aegyptiacus, published in 1654. In it, he put his ideas about the connections between ancient religions and Egypt into practice and claimed to have deciphered the hieroglyphs—with the Mensa Isiaca and several Egyptian obelisks (still in Rome today) assisting in this endeavor.

There’s quite a lot that could be said about Kircher. His work has been derided because of how much he got wrong. Yet, studying what was available to him, he did indeed get some things right about ancient Egypt. Oedipus Aegyptiacus, along with his Coptic grammar, are now considered some of the very earliest works of Egyptology. Unfortunately, one of the things he got right wasn’t the hieroglyphs. His hieroglyphic interpretations are both highly cosmological, highly Neoplatonic, and completely wrong. It’s all quite complex and I won’t go into it here, except for what he says about Isis.

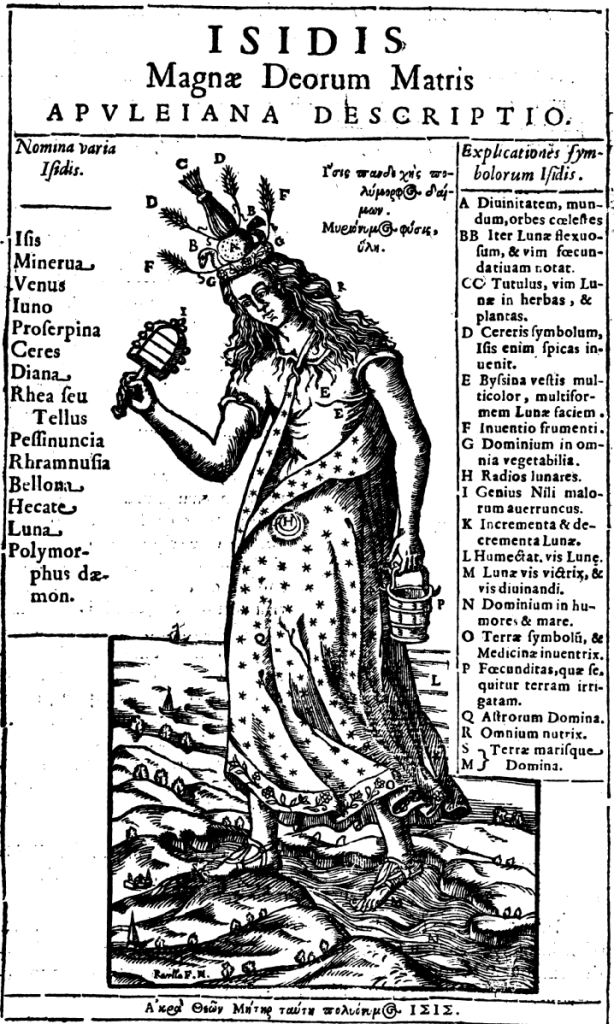

Kircher’s Isis

In Kircher’s Father-Son-Holy Spirit trinitarian scheme, Isis is—interestingly—the Son. Thus, She is the savior, just as she was in the the Hellenistic world. (Kircher had read his Apuleius.) In Oedipus Aegyptiacus, much of his Egyptian discussion is given under the heading, “The Temple of Isis.” By doing so, he was placing all of his Egyptian interpretations under the purview of the Goddess of Wisdom, our Lady Isis.

Since I don’t read Latin, when it comes to Kircher’s interpretations of the Mensa, I’m going to rely on W. Wynn Westcott’s translated quotes and discussion of Kircher’s text in his own book on the Mensa, The Isiac Tablet. Westcott was very much a fan of Kircher’s interpretation of the Mensa—and added his own interpretations as well.

Kircher’s and Westcott’s Isis

Westcott says that the philosophy and theosophy Kircher associates with the Mensa Isiaca is almost identical with that of the Chaldean Oracles, an important text to Neoplatonists, now only known from quotes in other works. And furthermore, that it also has much in common with the Hebrew Qabalah. Here, he quotes Kircher’s explanation of the Mensa:

The universe is regulated from the Paternal Foundation through three triads; this Foundation is variously called The Iynx, Soul of the World, the Pantomorphous Redeemer, and by Philo, the Constructive Wisdom, and exists in the perfection of triads of Pater, Potentia, and Mater, or Mens, the Father, the Power, and the Mother, or Design: coexisting with Faith, Truth, and Love.

Westcott, in The Isiac Table, quoting Kircher in Oedipus Aegyptiacus

Kircher is talking about the figure of Isis in the center of the Mensa as the Paternal Foundation. She is Isis and She is the Iynx, the Soul of the World, and the Panomorphous (All Formed) Redeemer. He goes on to say that the figures around Her are administrators of the Divine power in various spheres, such as the zodiac, the planets, and the winds.

Later, he says the central seated figure of Isis is “the Supreme Mind, or Pantomorphous Iynx Multiform Sphynx or Logos, Word, or Soul of the World, and is placed here in the middle, as in the Centre of Universal Nature.”

Isis’ enthroned posture means dominion and power; the dog on Her throne (looks more like a cat to me) is because “the Isiac Iynx is associated with the Dog Star, Sirius.” Her winged clothing “denotes the sublime velocity of the higher powers.” Each and every detail of the image is given mystical significance. (It’s a lot, so I won’t include it here. What’s more, almost every figure in the Mensa, he considers to be a form of Isis…She’s pantomorphous, after all.)

Some things he gets right. For instance, he says the disk and scarab represent the sun. Other things don’t match what we know about Egyptian symbolism, but gain meaning through Kircher’s mystical exercise. For instance, the alternating black and white stripes on the lotus-form columns represent the ups and downs of earthly life, which Isis as “the mother of Universal Nature” rules.

All in all, Kircher’s decoding of the Mensa Isiaca reveals cosmic Mysteries containing the Wisdom of the Egyptians, with Isis in Her many forms guiding and controlling the multifaceted Universe throughout.

Kircher Isn’t the Only One

The importance Kircher gives to Isis, and his ongoing influence, especially in esoterica, is one of the keys that helps us understand why Isis continued to be such an integral part of the western spiritual imagination. Through works such as Kircher’s, She remained an important part of the Western Mystery Tradition.

Well, I’m at the end of this post and we’re still not quite to the end of this exploration of the Mensa. I thought I’d be able to do it in two, but it looks like three will be the charm. So next time we’ll look at what some other historians and occultists had to say about the Mensa. And I’ll tell you about a weird synchronicity that happened for me in relation to these posts.