I’m going to be talking with Janus Sunaj and Domonic of the Magician and the Fool podcast next week about the Mysteries of Isis…and probably some other things, too. I’ll let you know when the podcast is available. In the meantime, here are some speculations about Isis, Egypt, Greece, and the Mysteries…

Most modern scholars now accept the influence of ancient Egypt on ancient Greece. We are finally able to take ancient Greek writers a bit more seriously when they tell us that—well, yes—the fractious city-states of Greece were indeed impressed and influenced by the ancient-even-then, ever magical, amazingly unified, and seemingly peaceful land of Egypt.

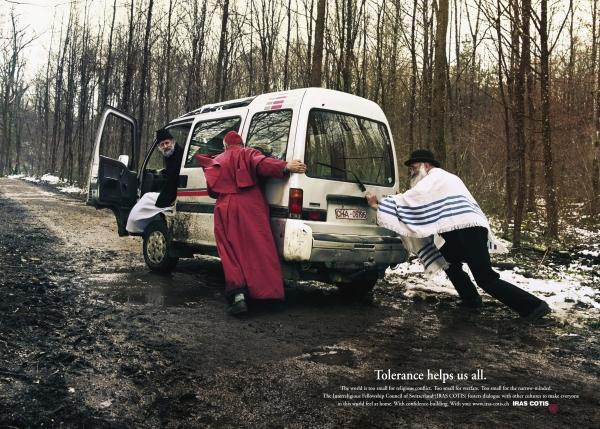

Hey, nobody operates in a cultural vacuum and the ancients didn’t either.

Writing in the 5th century BCE, the Greek historian Herodotus told his readers flatly that in the Egyptian language Demeter is Isis. In fact, he seems convinced that most of the names of the Greek Deities and many of the Greek religious rites came to the aboriginal Greeks, the Pelasgians, by way of Egypt. Among these rites are the famous Greek women’s rites of Demeter called Thesmophoria.

In his essay On Isis and Osiris, the Greek priest Plutarch remarks that “Among the Greeks also many things are done which are similar to the Egyptian ceremonies in the shrines of Isis, and they do them at about the same time.”

Diodorus Siculus, a Sicilian historian, records that Erechtheus, the mythical king of Athens, was himself Egyptian and it was he who instituted the Eleusinian rites after obtaining grain from Egypt during a Greek famine. He also said that the Eumolpids, the family that traditionally ran the Eleusinian Mysteries, were of Egyptian priestly stock.

How seriously should we take this? Could there be an Egyptian seed at the center of the defining Mysteries of ancient Greece, the Eleusinian Mysteries of Demeter and Kore?

It is quite true that we have no incontrovertible proof of an Egyptian origin of the important Eleusinian Mysteries. We do, however, have interesting footprints to follow up. We know for certain that either Egyptians were at Eleusis or that Greeks brought Egyptian talismans to Eleusis for Egyptian scarabs and a symbol of Isis, which date to the ninth or eighth century BCE, have been discovered there. The eighth century is the time to which the Eleusinian rites are usually dated, though it is likely that their true origins go back further, even if the rites were not in the form they eventually took.

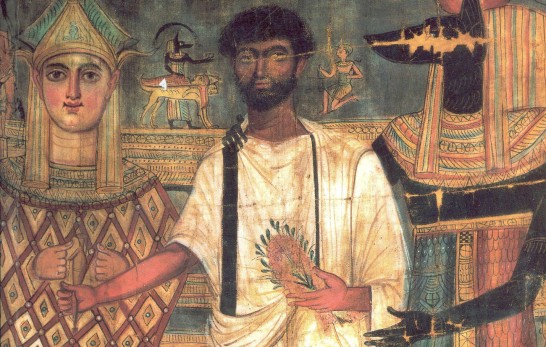

The correspondences between the Eleusinian myth and the Isis and Osiris myth as related in Plutarch are notable: the search for a missing Divine Beloved, the mournful aspect of the searching Goddess, the connection of the Beloved with the Underworld, and the (possible in the case of Eleusinian myth) birth of a Divine Child. Plutarch’s 2nd century CE rendition of the story is usually seen as Demetrian influence on Greco-Egyptian Isis and Her Greco-Roman Mysteries. But what if it was the other way around?

There are scholars who have traced magical formulae from Egypt to Greece, then followed them as they returned from Greece—changed—to be re-adopted in Egypt at a later period. Perhaps something like that happened with the Eleusinian/Isis-Osiris myth. While the basis of the myth—missing Beloved, searching, mourning, finding—may have its roots in Egypt, by the time it came back to Egypt, it had been changed. For instance, the “weeping at the well” incident in both the Demeterian myth and Plutarchian Isis myth is not found in any Egyptian rendition of the Isis and Osiris tale. It would indeed seem that this revised piece of the story was adopted from Demeter’s myth into that of Isis.

While this is speculative, it’s not just me speculating. There are actual scholars thinking along these lines. One of them is the highly controversial Martin Bernal (author of Black Athena, which traces African origins for a great deal of Greek culture). The much less controversial Walter Burkert has something to say about eastern influence, too, in his The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age. Even scholars of a more classical bent admit the influence of Egypt on early Greece, especially in matters of religion.

Bernal’s work as a whole should not be dismissed just because he goes too far in some cases. In my opinion, overall he’s right: Egypt particularly, as well as other long-established near eastern nations, exerted a huge influence on early Greece in its formative stages. Once Greece became established, of course, it developed its unique culture. But again, no culture exists in a vacuum. We are all influenced by each other.

Bernal spends a lot of time making etymological connections (etymology is the study of word origins) which are, at the very least, interesting. For instance, there are a number of Eleusinian terms that have no Indo-European cognates, yet can be explained in terms of ancient Egyptian or West Semitic. I won’t go into all the details because, if you’re not an etymologist, you might start to snore. One of these terms is the word “mysteries” itself. While it is usually explained as coming from an Indo-European root that refers to “closing the mouth” or staying silent, Bernal suggests that it might be better and more directly explained by an Egyptian root that refers to secrecy.

In this scenario, “mysteries” is derived from ancient Egyptian em sesheta (you can see the “m” and “s” sound there), meaning “in secret.” Sesheta, “secret,” was a word often used in relation to the Isis-Osiris rites, as well as other Egyptian rites.

Bernal also make connections between Greek words associated with the Mysteries and other Egyptian words, but frankly, I don’t have enough etymological background to judge. For instance, Bernal offers a connection between the Greek root of telete (initiation), which also means “completion” with the Egyptian djer, meaning “limit, end, or entire.” (You may recall this word from our discussion of Nephthys as the Lady of the Limit during the last few weeks.)

As I mentioned earlier, Diodorus Siculus recorded the tradition that the Eleusinian priestly family, the Eumolpids, were originally Egyptian. The ancient Greek scholar Apollodorus said that the Eumolpids were from Eithiopia. Apparently the Eumolpids themselves believed they had Egyptian origins, while others said they were from Thrace. Bernal suggests that the name Eumolpid, as well as the name of the second Eleusinian priestly family, the Keryxes, who served as Sacred Heralds, have plausible Afroasiatic origins. In fact, he thinks that Greek keryx comes from Egyptian qa kheru, “high or loud of voice.” And that, if true, is extremely cool.

Of course, the big thing that may have come to the Greeks from Egypt is the idea of a blessed life after death. In the work of early Greek poets like Homer, the afterlife is a place of wan grey ghosts and no joy. Where did the idea of a joyful afterlife—for initiates, anyway—come from? Surely, surely it was influenced by Greece’s neighbors to the south, where they were well-versed in the ways of the afterlife and its joys, assuming one knew the proper passwords and pathways. It seems likely that this knowledge, which would have been sesheta until Books of the Dead became more widely available for everyone in Egypt, could have been turned into a Mystery cult at Eleusis, where a Goddess searched for a missing Beloved, eventually found Her, though She was forever changed having become the Queen of the Dead, and then bestowed the Mystery of a blessed life after death on Her initiates.

And we haven’t even gotten to the harmonies between Isis and Demeter, which are much more interesting than just Their “Mother Goddess” connection. Perhaps we’ll go there next time.